|

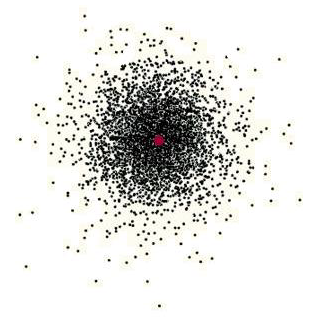

| Probability pattern for a single electron |

One of the major critiques of determinism as a theory of mind, is that because all matter can only ever be explained by probabilities of quantum states, that it is thus impossible to claim that there is a direct causality between the atomic structure of neurons in the brain and conscious thought. Because conscious thought is a much larger, emergent phenomenon, this sort of reductionist determinism can't possibly account for the richness of human thought.

But I don't think that reductionist determinism is trying to explain all of consciousness. It is only claiming that consciousness is rooted in structures of atoms, just like anything else in the universe, from a hammer, to a computer program, to a hurricane. It doesn't pretend to explain something like qualia, or what a fish feels when it bites a worm. But it reasonably assumes that such states of mind exist because of particular states of matter, arranged as they are in specific ways so that these states of mind may emerge. We have direct evidence that thoughts are rooted in atomic structures because we know that neurons fire when brains think, and specific kinds of thinking are confined to certain structures of the brain. We have even measured specific thoughts as consistent patterns of electrical energy.

And determinism is evidenced by more than reductionism. It takes into consideration other forms of understanding, forms that we are presently far from being able to trace to a specific set of atoms, and possibly never will be able to, due to physical, and possibly conceptual limitations. (After all, we're dealing with trillions of neurons firing in coordination.) There are many ways in which human consciousness can be partially explained, that point to determinism. By analyzing behavior, patterns of learning and thought, and the physiological mechanisms underlying many emotional states, we derive insight into the mind. For example, we can study memory formation, and the brain's ability to learn when subjected to stress. That is a deterministic process. We can study cognition and frameworks within which ideas are formed, and trace their logic to prior knowledge and learning. That is deterministic.

The key question of free will involves why we make one choice over another. Proponents of free will say we freely consider the options and then choose. The reductionist framework simply argues that this can't be so, because if thoughts are structures of atoms, then there must be causality. Even if we are talking not about perfect causality but probabilities of quantum states, we are still talking about a rough determinacy, a range of probabilities, that seems more than adequate to imply direct causality between the goings on of atoms in our brains.

Stephen Hawking describes black holes as the ultimate example of the indeterminacy of the universe. He describes them as acting on particles such that the causal links between time and space are at some point ultimately severed. Yet he reminds us that this is only an incredibly extreme example, implying that it does little to alter what we ought to expect of the observable world.

One might not think it mattered very much, if determinism broke down near black holes. We are almost certainly at least a few light years, from a black hole of any size. But, the Uncertainty Principle implies that every region of space should be full of tiny virtual black holes, which appear and disappear again. One would think that particles and information could fall into these black holes, and be lost. Because these virtual black holes are so small, a hundred billion billion times smaller than the nucleus of an atom, the rate at which information would be lost would be very low. That is why the laws of science appear deterministic, to a very good approximation.

So even if I feel like I am freely choosing whether to put one lump or two of sugar in my coffee, there must be still something structural in my brain that is causing me to make one or the other choice, even if that something is operating within a range of probabilities at the quantum level. A better way of thinking about this might be to say that when I reach for the spoon, it most certainly will be there, even if not entirely certainly.

Now, we don't know what that the structure of the brain that gives rise to consciousness looks like - it is likely an insanely complex string of neural interactions firing in fractions of a second. But we know that it requires a great deal of prior knowledge - sugar, spoons, coffee, balance, predicted taste, health concerns, etc., all in coordinated calculation. We also know that there are many unconscious pressures at work, even if we couldn't begin to account for them all. (Unconscious thought is the least understood aspect of consciousness, yet probably the most powerful evidence for determinism, as it constitutes an essential element of thought, yet is by definition outside the realm of choice, and actively shaping thought in ways we can never be certain of. At the very least, it is a severe limiter of freedom).

No comments:

Post a Comment