I used to

be more interested in consciousness. The question of what it was and how

it happened seemed fundamental to understanding why humans do what we do.

The "problem" of consciousness was key to the question of free

will, which all broader questions of social politics seemed to hinge on.

It was a decades-long, rambling trip which

ultimately - quite by chance - led me to behaviorism, the actual science of

behavior, which generally puts this question to bed. Or at least tucks it

in nicely. Not that the explanation is complete, but there is plenty of basic

science from which to derive a solid foundation on the matter.

Of

course, this understanding is far from mainstream, for a variety of reasons.

In the main, it is an unintuitive understanding: "I" plainly

choose my behavior, do I not? Free will seems self-evident. But as is

often the case with "common-sense" intuition, this evidence is a cultural

construct. We live in a world in which the individual is assumed to be

the master of his own destiny. In the majority of Judeo-Christian

religions, common interpretation views man as a free actor in a morality play,

choosing between the temptations of the devil and religious teaching, each

moment the crux of an epic, metaphysical struggle. Our legal system

follows suit, as it has tended to since its founding. The

"guilty" is he who could have acted differently but chose not

to. Our economic system also follows, assuming the profit of man's

economic actions to be his own responsibility - whether leaving him destitute

or in gilded chambers.

The

intuition-based concept of the Free man is thusly reinforced everywhere through

social institutions at every level. But the meat of the intuition, fundamental to these larger structures, is a philosophical game we have all learned to play.

Behaviorists call it "mentalism", and it is as essential to our

early formation as the milk in our baby bottles. In his paper Behavior Analysis, Mentalism, and the Path to Social Justice(2003), Jay Moore writes:

...Mentalism may be defined as an approach to the study of

behavior which assumes that a mental or "inner" dimension exists that

differs from a behavioral dimension. This dimension is ordinarily referred to

in terms of its neural, psychic, spiritual, subjective, conceptual, or

hypothetical properties. Mentalism further assumes that phenomena in this

dimension either directly cause or at least mediate some forms of behavior, if

not all.

Examples

of mentalism are rife in our language. People get in fights because they

are "angry". People don't do their work because they are

"lazy". People do great things because they are

"driven". The list of adjectives supposedly describing

causative inner states is endless. People act because they are: smart,

dumb, ambitious, shy, calculating, cruel, evil, compassionate, kind, generous,

stingy, clever, funny, quiet, rambunctious, etc.

Yet what

are these words actually describing? People certainly behave in ways that

have these characteristics. However, this is not an explanation but

rather a description of past behavior, and an educated guess as to how they

might behave in the future given similar circumstances. The problem with

mentalisms is that they can easily become circular: a person acts a

certain way, is described with a mentalistic term, and the term is then purported

to be the cause of the behavior.

The

so-called "cognitive revolution" in the social sciences, heralded in

by Noam Chomksy's (1959) famously vicious critique of Skinner's landmark

work, Verbal Behavior, was predicated on the notion that mental

events are indeed causative. To this day, cognitivists use the

architectural language of the personal computer to seek out causation,

hypothesizing mental events using computational terms like memory, processing

and algorithms. However to Skinner, all of this is merely further

description. Even if one were to develop a precise cataloguing of every

possible rotation of the smallest molecular particle involved in the process of

say, my daydreaming about fishing for trout, it would still have nothing to say

about what actually causes my thinking behavior.

Here, the

behaviorist has the advantage of being informed by science, more specifically

the science of behavior. A core principle of radical behaviorism is that

a a science of behavior is possible. That is, behavior is a deterministic

process which can be understood without appealing to non-physical events.

In short, to quote William Baum (1994), "A science of human behavior

is possible". To the behaviorist, the structure of the

moving parts - while certainly an honorable and interesting subject

phenomenologically - are secondary to the larger truth of causation: that

behavior is a product of an environment acting upon the genetic make-up of an

organism over time. Behaviorists design experiments to manipulate environmental

variables, in order to find controlling relationships with variables in the

organism that are dependent on the manipulation.

However,

society is still firmly in the camp of the structuralist. While I realize

there is an element of simplicity to the notion that to completely understand a

thing is to account for all of it's parts, I've long been suspicious that the

zealous embrace of Chomsky's attack on Skinner was ultimately more about a

cultural zeitgeist than anything else (In 1971, Chomsky showed his cards a bit

when he wrote a statement so absurd it offers a clue to his sense of deep

ideological resentment: "At the moment we have virtually no scientific

evidence and not even the germs of an interesting hypothesis about how human

behavior is determined").

America

was entering the 1960's, and libertarian rebellion was fomenting against the

strictures of the past. Nothing less than a quasi-religious awakening

was occurring, which sought to bust the shackles of old institutional dogma and

paint a road to enlightenment upon the canvas of the expanding mind. In

the eyes of the many on the left, institutional knowledge had brought us the

atom bomb, Vietnam, sexism, racism, and the suit and tie. To many on the

right, scientific knowledge was less suspect, but to the extent that it

encroached upon the established order of institutions such as the church,

marriage, and capitalism (communism was an existential threat almost nothing

ought not be sacrificed to prevent), it was dangerous for different reasons.

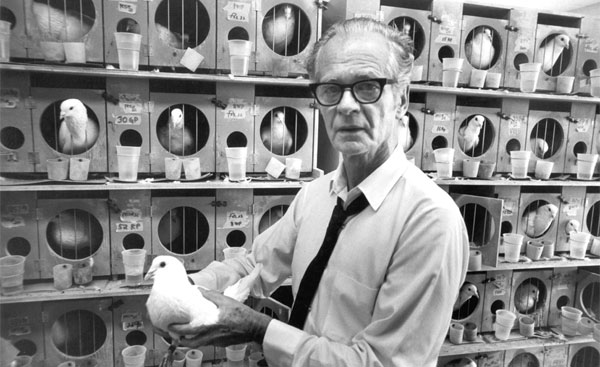

Skinner's

Verbal Behavior could not have come at a worse time. In it, he laid out

the most detailed and cogent argument yet for a radical behaviorism in which

all of human behavior - including thought itself - was under the control of

physical contingencies. In his suit and tie, with his cumulative records

and operant chambers, he represented everything the left despised. As

Camille Paglia (2003) argued in her essay Cults and Cosmic

Conscousness: Religious Visions in the 1960's, the 1960's was a time of

"spiritual awakening" and "rebellious liberalization", just

one of many religious revivals in American history. She likens the period

to Hellenistic Rome, in which "mystery religions" rose up in response

to an oppressive institutional order. Dionysianistic practice emphasized

"a worshipper's powerful identification with and emotional

connection" to God. She goes on to note the context in which a

certain long-haired man in sandals rose to prominence:

The American sixties, I

submit, had a climate of spiritual crisis and political unrest

similar to that of ancient Palestine, then under Roman occupation.

In the 20th century, the culture moment was

projected through popular media icons such as Frank Sinatra, Elvis, Jim

Morrison and the Beatles: each embodied the generation's desire for personal

emotional liberation and sexual independence. Describing a strange

episode in which rumors circulated of Paul

McCartney's premature death:

The hapless McCartney had become Adonis, the

dying god of fertility myth who was the epicene prototype for the deified

Antinous: after Antinous drowned in the Nile in 130 ad, the grief-stricken

Hadrian had him memorialized in shrines all over the Mediterranean, where

ravishing cult statues often showed the pensive youth crowned with the

grapes and vines of Dionysus.

Burrhus

Frederick Skinner, with his measured demeanor and supremely rationalistic style

of communication, was the very opposite of Adonis.

On the

right, his argument was often viewed as nothing less than paving the way for

godless totalitarianism. Indeed, in his 1971 Beyond Freedom and Dignity,

he writes:

A free economy does not mean the absence of economic

control, because no economy is free as long as goods and money remain

reinforcing. When we refuse to impose controls over wages, prices, and

the use of natural resources in order to not interfere with individual initiative,

we leave the individual under the control of unplanned economic contingencies.

(emphasis added)

The

critique, whether or not its fear that radical behaviorism leads to a state

controlled economy is quite irrelevant to Skinner's point: if human behavior is

controlled by contingencies, then they will be in effect no matter what type of

economic system one chooses.

On

campuses across America (Europe had never quite embraced behaviorism to begin

with), young students (future professors) of psychology took up the banner of

cognitivism and never looked back. Never mind that most of them likely

never bothered to read Verbal Behavior. Granted, it is a difficult book.

Radical behaviorism is a concept which requires a good degree of

open-mindedness, and courage to go where the evidence takes you, rather than

relying upon the safety of old cultural intuitions. It no more paves the

way to totalitarianism than does Darwin's theory of evolution pave the way for

eugenics. But like evolution, radical behaviorism is rather unintuitive.

Both are selectionist. In evolution, the organism is the product

of a biological shaping process extending back through time, with each

generation. There is nothing in the structure of the organism per-say,

that "is" evolution. The only way to understand evolution is by

examining the relationships between organisms - which have been selected -

over long periods of time. Similarly, radical behaviorism says

there is no thing in the organism that "is" behavior. Rather,

the behavior is selected for over the course of the organism's lifespan.

Just as

the genetic configuration is selected for that most suits the organism to its

environment, the organism's patterns of behavior are selected for which have

been most reinforcing. Just as the genes for a white coat have been

selected for as most beneficial for polar bears hunting in the arctic ice, the

behavior of speaking the phrase "Where is the restroom?" has been

selected for as most beneficial in English verbal communities. Once

familiar enough with the basic science of evolution, the concept isn't too

difficult to grasp. I think the same can be said for radical behaviorism.

Most

people never have to fully grasp the complexities of the science of evolution -

radiocarbon dating, genetic drift, sedimentary rock, random mutation, etc - in

order to embrace it. Instead, they can rely upon an environment in which

the "settled" science immerses them from grade school to instill in

them an intuitive grasp of geologic time and the notion of natural selection.

The science of behaviorism has no such mainstream acceptance.

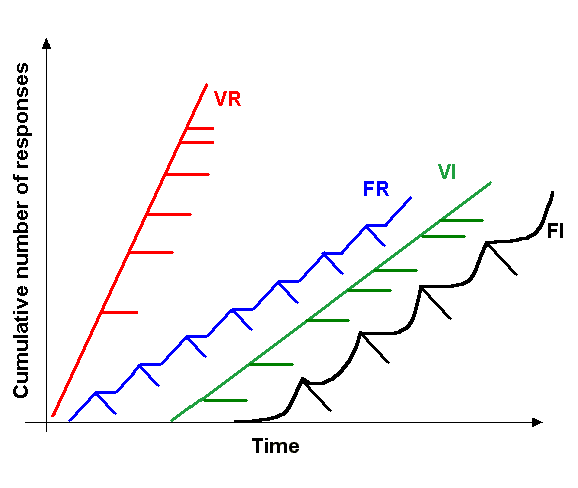

Therefore concepts such as discriminative stimuli, schedules of

reinforcement, the matching law, respondent versus operant, extinction bursts,

establishing operations, etc. are not considered "settled" outside of

the field and no such intuition is able to be built.

Rather,

mentalistic accounts of behavior rule the day with nearly the degree of vigor

that they did a hundred or even a thousand years ago. In this sense,

society operates with a basic psychological outlook that could quite easily be

considered medieval. Indeed, one only need look towards subjects such as

criminal justice or income disparity to see where such thinking leads - in

which "driven" men claim moral right to mansions, and

"evil" men are delivered to concrete cells of solitary confinement.

So too in

our daily lives do we encounter the suffering and anxiety caused by confusion

over the basic principles of behavior. Intuiting the actions of others as

being caused by them, we become resentful and intolerant,

blinded to the reality that their actions are the result of the contingencies

in their lives.

Further

still, we turn this false mentalism upon ourselves, believing falsely that

there is something in us that is responsible for our actions,

as opposed to the contingencies within which we are shaped. Just as we

develop toxic emotions as a response to others, we develop it in response to

our own "self". We imagine this entity as responsible for

actions we would rather not have occur. This leads us down the fruitless

path of "becoming better people", and looking only into our own

thoughts and feelings, rather than examining the functional relationships

between our environment and our history of reacting within it. We have

been sold on the notion that there is something wrong with how we

"process" the environment, rather than our behavior being a perfectly

natural, learned response to environmental contingencies.

The

cognitive revolution did not represent a shift from a centuries-old

deterministic, mechanistic view of behavior in which Free man did not exist, to

a new view in which Free man existed as a function of a "self" which

processed information and chose to act based upon some emergent, metaphysical

system. Rather, for hundreds or even thousands of years, Free man was

commonly assumed to exist as an independent actor responsible for his own lot

in life, and it was only for a brief period - a few decades - that behaviorism

developed and held sway in psychological study. Aside from it being a

mature, complex field of study with numerous insights into human behavior, to

the extent that cognitivism rejects a behavior analytic approach in favor of

appeals to mentalism, the cognitive revolution would better be described as a

"cognitive reversion" to the old, intuitive conception of

"self" that has always been foundational to religious, economic and

civic institutions.

However,

as fitting for a revolution, cognitivist mentalism indeed led to a widespread

purging of behaviorism as a respectable science. In The Structure of Scientific

Revolutions (1970), Thomas Kuhn writes of this process:

When it repudiates a past paradigm, a scientific community

simultaneously renounces, as a fit subject for professional scrutiny, most of

the books and articles in which that paradigm had been embodied. Scientific

education makes use of no equivalent for the art museum or the library of

classics, and the result is a sometimes drastic distortion in the scientist's

perception of his discipline's past. More than the practitioners of other creative

fields, he comes to see it as leading in a straight line to the discipline's

present vantage. In short, he comes to see it as progress. No alternative is

available to him while he remains in the field.

To the

hapless psychology student, there is simply no point in engaging with

behaviorism beyond the most primitive level. Textbooks routinely dismiss

Skinner's work as, while describing an important part of human behavior,

antiquated when it comes to dealing with the true complex natural of human

behavior. While is is sometimes suggested that cognitive science

hasn't abandoned behaviorism, but rather quietly subsumed it,

David Palmer (Behavior Analyst, 2006) argues the contrary:

....Such examples suggest that, instead of building

principles of behavior into its foundation, cognitive science has cut itself

loose from them. Cognitive psychology textbooks neither exploit nor review

reinforcement, discrimination, generalization, blocking, or other behavioral

phenomena. By implication, general learning principles are peripheral to an

understanding of cognitive phenomena. Even those researchers who have

rediscovered the power of reinforcement and stimulus control hasten to distance

themselves from Skinner and the behaviorists. For example, the authors of a

book that helped to pioneer the era of research on neural networks were

embarrassed by the compatibility of their models with behavioral

interpretations: “A claim that some people have made is that our models appear

to share much in common with behaviorist accounts of behavior … [but they] must

be seen as completely antithetical to the radical behaviorist program and

strongly committed to the study of representations and process”.

In my

personal experience, I routinely encounter Psychology graduates who possess

little more than a rudimentary understanding of behavioral principles.

If the general education teachers I worked with in public schools were

consciously applying behavioral principles in their classrooms, they certainly

never spoke of it. In my own training, as an undergraduate in Social

Sciences, and as a graduate in Elementary Education, Skinner's work received at

most a total of one lecture in an undergraduate course, and a paragraph or two

in graduate school. His work on operant conditioning, while acknowledged

as important to understanding learning at rudimentary levels, is quickly passed

over in favor of the work of cognitive theorists such as Vygotsky (zone of

proximal development, scaffolding), Piajet (schema), Bandura (social learning)

and Erickson (psychosocial development), who are commonly viewed as offering

something more than would be possible through adherence to behaviorism alone.

Their work is commonly viewed as refuting behaviorism, and thought of as taking

our understanding of learning further, in ways that would be impossible under a

behavioral analytic approach, and thus more critical to learning and social

development. While their insights are indeed valid and useful, to view

them as in any way a refutation of behavioral principles would be a serious

error. Each these theorist's work can easily be accounted for via the

application of behavior analytic principles. Ironically, to the

extent that these cognitive theories fail to engage with the scientific,

behavioral principles underlying their existence, they are in their own way

reductionist; to properly understand the concepts of zones of proximal

development or schema without taking into

consideration principles such as establishing operations,

generalization, learning histories or schedules of

reinforcement is to reduce these phenomena to vague simplifications.

Yet simplification, especially when presented in the context of a

compatible reinforcement history, is itself highly reinforcing. To an

individual raised to believe in an all-powerful God who is communicated in an

inerrant bible, the notion of divine creation of man in a short period of time

is much easier to embrace than a chaotic process of natural selection over

hundreds of millions of years.

The first

edition of On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, but

the theory of evolution wasn't widely accepted until decades later.

Widespread public acceptance wasn't gained until perhaps the 1940's, with

the Catholic church eventually allowing that evolution is at least compatible

with the bible in 1950. Still, to this day evolution remains a

controversial theory accepted by only 60% of the populations in the U.S. and

Latin America, according to Pew Research (2015). In many respects, the

evidence for evolution is more clear-cut, in that developments in multiple

areas of science - from biology to geology to particle physics - have played a

key ole in its understanding. The structure of DNA was not even

understood until a century later. In many respects, our understanding of

the brain, the most complex object known in the universe, is much less far

along. For behavior skeptics, an emphasis on structuralism combined with

mentalistic bias, points toward an almost unfathomable complexity.

Indeed, consciousness has famously been coined as "the hard

problem" - an rather mythical designation. Behaviorists who question

whether the problem is all that hard are often labeled as "reductionists"

- too easily seduced by a naively simplistic account of a complex phenomena.

But the

radical behaviorist does not deny the complexity of the moving parts

(environmental stimuli, biological molecules, and past history). Rather,

he merely insists that at its core there is a deterministic, functional

relationship at work. I'm often struck by the similarity with the

"Intelligent Design" argument put forth by evolution skeptics.

Biological organisms are claimed to be "irreducibly complex",

so as to never have been able to originate without an intelligent designer.

Yet this argument also chooses to misdirect attention to the structure of

the organism, to seek an understanding of it removed from the context of

history. And just like evolution can only be understood as a function of

geologic time and the interplay between genes and environment, so too can

behavior only be understood as the interplay between the phylogeny (genetic

history) and ontogeny (environmental, life history) of an organism.

Compared

with Darwinian evolution, the rate of acceptance of radical behaviorism over

cognitivist mentalism may not be in terrible shape. Maybe by the 2040's

we'll have seen a steady shift towards a behavior analytic approach.

However, I have my doubts. Evolution's largest direct social

implication might have been a sound refutation of biblical literalism.

But that was never so central to our institutions. Religious

freedom, after all, had long been enshrined in our constitution.

The

threat from the radical behavioral perspective to the established institutional

order is in my view much greater, in that it provides scientific justification

for the moral claim that as social products, ultimate accountability lies in

the system we build for man, not for man's actions within that system.

How to redraw our institutions so as to align with this truth is the real

challenge. But we must begin with the premise that, to the extent that it

is founded in mentalistic notions of human behavior, the current system is not

only unjust, but misguided and philosophically corrupt. There are a great

many aspects to the current order that are reinforcing to behavior that

preserves it, not the least of which is simple human greed (the tendency to

accumulate wealth in a manner that is unjust). But the opposite of greed

is generosity, and generous acts are simple to argue for. What is more

difficult is the untangling of the mentalistic rationale for systems that allow

the behaviors of human greed.

Baum, W. M. (1994). Understanding behaviorism:

Science, behavior, and culture. New York: HarperCollins.

Chomsky, N. (1959). ”A Review of B. F.

Skinner's Verbal Behavior”. Language, 35, No. 1, 26-58.

Kuhn, T. (1970). The Structure of Scientific

Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Moore, J. (2003). Behavior Analysis, Mentalism,

and the Path to Social Justice. The Behavior Analyst. 26 (2), 181. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2731454/pdf/behavan00006-0003.pdf

Chomsky, N. (1971). The Case Against B.F.

Skinner. The New York Review of Books. 17(11), 3. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/1971/12/30/the-case-against-bf-skinner/

Paglia, C. (2003). Cults and Cosmic

Consciousness: Religious Vision in the American 1960s. Arian 10 (3),

60-61. http://www.bu.edu/arion/files/2010/03/paglia_cults-1.pdf

Palmer, D. (2006) On Chomsky’s Appraisal

ofSkinner’s Verbal Behavior: A Half Century of Misunderstanding. The Behavior

Analyst. 29 (2), 260.

Skinner, B.F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. MA:

Copley Publishing Group.

Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond freedom and

dignity. New York: Knopf.

“Religion in Latin America: Widespread Change in

a Historically Catholic Region.” Pew Research Center, Washington D.C. (Nov. 13,

2014)http://www.pewforum.org/2014/11/13/chapter-8-religion-and-science/, 07/02/2016.

“US Becoming Less Religious,” Pew Research

Center, Washington D.C. (Nov. 3, 2015)

-->