A conversation I had with one of my students this week seemed to illustrate perfectly the sort of double-edged sword that is our broken immigration policy. I can't actually vouch for any of his story being true, but it seemed perfectly genuine as he explained it to me.

"Armando" was born in the US - San Diego, specifically, where his mother had explicitly traveled for the purposes of guaranteeing him papers. They then returned to Mexico for some brief period, after which they moved permanently to the US.

Armando plays tough, but is a softy at heart. He wears the gang clothes and talks the gang language (generally bragging about the fights and drugs he does). Having ended up credit deficient at a continuation high school, his stubborn attitude toward schoolwork belies a healthy intellect and focus when he wants it. His plan is to get his GED and move to Santa Monica, live with a friend and take culinary arts classes at the community college.

But like many of his peers, he expresses an ebullient contempt for the world. "Life sucks," he says. More specifically, "people suck." Why? "You can't trust 'em". Recently his car was broken into and all of his expensive stereo equipment was stolen. Life seems all daggers.

Armando was kicked out of the comprehensive high-school for selling drugs. So he decided to take a year off and not go to school at all. I asked him why he was selling drugs. "For the money," he told me, explaining that he needed to help pay the bills. "I had to after my Dad got deported." I asked him if his mother knew where the money was coming from. He had a construction job on the side and told her the money came from there. But he isn't selling drugs any more.

Why not, I asked. "Because my Dad came back".

A bastard's take on human behavior, politics, religion, social justice, family, race, pain, free will, and trees

Showing posts with label immigration. Show all posts

Showing posts with label immigration. Show all posts

Friday, October 29, 2010

Sunday, July 11, 2010

A Case for Open Borders

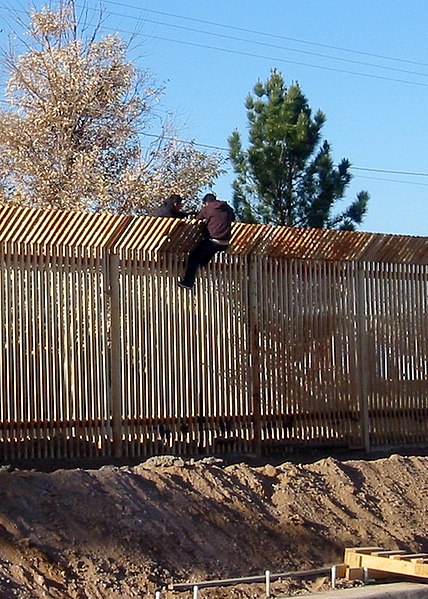

We're stuck in an odd place in America today where immigration is concerned. On the one hand, nearly everyone agrees that we must have closed borders, with selective admissions. But the fact is that millions of illegal immigrants are already here, and many more are in the process of coming. Building a truly secure border would require expensive fencing, cameras and patrol units. Even then, there would likely be gaps.

So we are faced with tackling the problem via law enforcement. Employers of illegal immigrants are targeted, and any illegal immigrants found are deported. Yet this solution is difficult for various reasons. Employers have many incentives to hire illegal immigrants. They are plentiful, willing to work for little pay, and as illegal immigrants they are easier to exploit (poor conditions, safety hazards, regulations, etc.). The immigrants have every incentive to work as they have risked all to be here. Surviving without work is much more difficult. Dealing with state welfare institutions is either impossible or puts them at risk of deportation, as does any illegal activity.

From a human rights standpoint, every action targeted at illegal immigrants threatens American citizens who might find their rights diminished. The balance of rights vs. security is an old and complicated one. We must find a compromise between what rights we are willing to see sacrificed for every new security we agree to. With the vast majority of illegal immigrants coming from the Mexican border, being a largely Hispanic population, new security measures designed to target illegal immigrants is going to affect Hispanic Americans disproportionately. We see this in the new Arizona law sb1070 which places Hispanics in Arizona at much greater risk of having their rights violated.

A further complication, and one which may be the most tragic of all, is the issue of birthright citizenship and family dissolution. Illegal immigrants often either bring their families with them to America, or have children once they are here. If one parent is arrested and deported, the consequences to the family are severe. In many cases the children might have been here illegally, possibly for most of their lives, and thus arrest and deportation means incredible burden. If a child has citizenship, the family is then faced with the prospect of how to secure for them the future they were guaranteed by law.

So this is where we are. All of this is going on now, with no likelihood of change in the near future. Profound resentment, especially in these economic times, has reached the boiling point. The governor of Arizona is literally either making up stories herself, or repeating the lies of others:

But I wonder whether we should even have closed borders at all. My general outlook on life is to not believe in anything without a good reason for doing so. Because many issues are so complicated, the authority of experts must often be trusted. Other issues are less empirical, and more matters of philosophical principle. Other issues are a robust combination of both - the experts disagree, and philosophical principle isn't unimportant. As illegal immigration seems to fall into this last category, I feel comfortable taking the radical stance that what America needs to be doing is opening our borders to most anyone who desires entry.

According to Wikipedia, the main arguments against borders are as follows:

The only argument I see holding much validity is number 2.

On numbers 1 and 3, I see no real threat to public safety from open borders. The vast majority of illegal immigrants are otherwise law-abiding, and criminals have not seemed to have been deterred much so far. In fact, because increased adds to the price of drugs, closed borders may in fact increase violent crime. On this front, a prevention program, possibly combined with legalization and taxation, that treats the problem of drug addictions seems a better, cheaper option.

On number 2, I'm not sure how much of a problem slavery and prostitution are. I see no reason that simple law enforcement shouldn't be given this task. Any gaps are likely already there, and the expense of a questionably secure border apparatus for solely this purpose seems inappropriate.

Number 5 isn't really an argument.

Now, it does seem reasonable to fear that completely open borders might trigger a mass-migration that the state wouldn't be able to handle. But there are a number of reasons to doubt this. First of all, if the labor market isn't able to handle them, the immigrants will quickly realize how limited their prospects are. The only alternative is then to either make ends meet through illegal means or seek help from the state. Neither seems a very attractive propositions for prospective immigrants. The idea of relocating hundreds or even thousands of miles to engage in criminal activity seems an odd life choice. What's more, illegal activity entails market pressures of its own. The state is already quite stingy with welfare payments. There seems no reason why it wouldn't still be able to require proof of citizenship for benefits.

A socio-economic and burden that does seem reasonable is the introduction of competition into the labor market. Even assuming that minimum wage laws would still be enforced, numerous occupations would suddenly face an influx of foreign workers. However, language and technical considerations would still give Americans an advantage. The occupations most at-risk would be those in which these forms of human capital would not be required to the same extent. This is the current greatest socio-economic impact of illegal immigration. There is little reason to think that it wouldn't only increase were we to open our borders.

This is where I have the most difficulty finding my own moral perspective. As a college-graduated, credentialed teacher, my job is in no way threatened by immigration. I could see future immigrants receiving credentialing and posing a threat, but that prospect doesn't seem to bother me. I know it may bother some, but I'm not sure whether I feel as though I have some God-given right to teach in America that any other equally-qualified candidate does not, regardless of citizenship. I'm perfectly willing to accept that because I face no real threat from immigrant labor competition, I am missing some possibly persuasively principled argument. But for now I can't foresee any.

As regular readers will note, I have a strong disposition towards viewing socio-economic achievement through the lens of social determinism; I believe the murderer is no more responsible for his actions than the millionaire. Maybe as such, I see no difference between an American citizen and a Mexican citizen. Why should an American have any more right to the American labor market than a Mexican? If there is no existential threat to our entire economy (in which case open borders would become moot as we would all be doomed), the difficulties presented are zero sum: any net cost to American workers presents a net gain to foreign workers.

It is at this point that I think the conversation becomes about abstract notions of nationalism, and what it means to be a citizen. I am entirely utilitarian in that I find the concept of nation-states compelling only in that they make sense in terms of practical governance. Government needs to represent the people for whom it exists. In this way the citizen gains access to democratic rights and privileges. For instance, it would not make sense to allow foreign citizens from around the globe to vote in local elections.

Foreign citizens need not enjoy every single right and privilege of citizens, but to the extent that it is practical for them to do so, they should be allowed them. As I have argued thus far, there appears no practical reason why foreign citizens should not be allowed full access to labor markets. In this way, foreign citizens would not be treated much differently than out-of-state residents. We see no problem with accepting labor competition from any other state in the union. Assuming there are no other social or economic costs, labor competition from foreign countries should be viewed no differently.

Alas, I'm afraid that there exists one last refuge in this argument, and it resides within the nationalistic notion of identity. While many Americans no doubt cling to some form of unconscious bias towards some mysterious cultural quality of "American" that in their mind serves as a line of separation between themselves and non-citizens; that somehow by being an American citizen you are in some way different, and as such entitled to special privileges. Obviously, any dark hatefulness under-girding this attitude is immoral. No human life anywhere on the planet should be considered more worthy than any other. To the extent that nationalism is used as the sole reason for valuing the quality of one life over another, the argument is really based in nothing more than personal greed and selfishness.

As has been pointed out many times before throughout our history, we are a nation of immigrants. Implicit in this conception is the idea that human liberty transcends all boundaries, especially that of the nation state. Inclusion in American society should require nothing more than an agreement to honor its rules and principles. If the only thing that separates an illegal immigrant from a legal one is whether one was given permission from the state to enter, granting that permission to all simply removes that technicality. As I mentioned previously, there is a necessary balance between security and freedom. To the extent that the foreign citizen represents no threat to our security, either economic, social or political, they should be allowed all the freedoms citizens enjoy. And that freedom includes the right to live and work here among us as equals.

So we are faced with tackling the problem via law enforcement. Employers of illegal immigrants are targeted, and any illegal immigrants found are deported. Yet this solution is difficult for various reasons. Employers have many incentives to hire illegal immigrants. They are plentiful, willing to work for little pay, and as illegal immigrants they are easier to exploit (poor conditions, safety hazards, regulations, etc.). The immigrants have every incentive to work as they have risked all to be here. Surviving without work is much more difficult. Dealing with state welfare institutions is either impossible or puts them at risk of deportation, as does any illegal activity.

From a human rights standpoint, every action targeted at illegal immigrants threatens American citizens who might find their rights diminished. The balance of rights vs. security is an old and complicated one. We must find a compromise between what rights we are willing to see sacrificed for every new security we agree to. With the vast majority of illegal immigrants coming from the Mexican border, being a largely Hispanic population, new security measures designed to target illegal immigrants is going to affect Hispanic Americans disproportionately. We see this in the new Arizona law sb1070 which places Hispanics in Arizona at much greater risk of having their rights violated.

A further complication, and one which may be the most tragic of all, is the issue of birthright citizenship and family dissolution. Illegal immigrants often either bring their families with them to America, or have children once they are here. If one parent is arrested and deported, the consequences to the family are severe. In many cases the children might have been here illegally, possibly for most of their lives, and thus arrest and deportation means incredible burden. If a child has citizenship, the family is then faced with the prospect of how to secure for them the future they were guaranteed by law.

So this is where we are. All of this is going on now, with no likelihood of change in the near future. Profound resentment, especially in these economic times, has reached the boiling point. The governor of Arizona is literally either making up stories herself, or repeating the lies of others:

"Well, we all know that the majority of the people that are coming to Arizona and trespassing are now becoming drug mules. They're coming across our borders in huge numbers. The drug cartels have taken control of the immigration. … So they are criminals. They're breaking the law when they are trespassing and they're criminals when they pack the marijuana and the drugs on their backs. I believe today and in the circumstances that we are facing, that the majority of the illegal trespassers that are coming in the state of Arizona are under the direction and control of organized drug cartels, and they are bringing drugs in."

"Law enforcement agencies have found bodies in the desert either buried or just lying out there that have been beheaded."The range of serious solutions to the situation basically range from complete security at the border no matter the cost and draconian raids and round-ups, to a more liberal policy of "amnesty", in which there is a "path to citizenship" that illegal immigrants can pursue that allows them to continue living and working here. The latter only differs from an outright open border policy in that immigrants are still deterred from entry at the border and businesses who hire illegal immigrants are penalized. This policy has been used in the past, however generally on a case-by-case basis.

But I wonder whether we should even have closed borders at all. My general outlook on life is to not believe in anything without a good reason for doing so. Because many issues are so complicated, the authority of experts must often be trusted. Other issues are less empirical, and more matters of philosophical principle. Other issues are a robust combination of both - the experts disagree, and philosophical principle isn't unimportant. As illegal immigration seems to fall into this last category, I feel comfortable taking the radical stance that what America needs to be doing is opening our borders to most anyone who desires entry.

According to Wikipedia, the main arguments against borders are as follows:

- That open borders are a threat to security and public safety.

- That, in prosperous countries, open borders would trigger massive immigration, straining the domestic economy.That closed borders are necessary to protect the domestic culture(s).

- That closed borders help to prevent criminals from smuggling drugs, guns and other illegal items in quantities across the border.

- That closed borders make it more difficult to smuggle people across a country's border for the purpose of slavery, prostitution and similar criminal activities.

- That open borders are unnecessary in countries with legal avenues for immigration.

The only argument I see holding much validity is number 2.

On numbers 1 and 3, I see no real threat to public safety from open borders. The vast majority of illegal immigrants are otherwise law-abiding, and criminals have not seemed to have been deterred much so far. In fact, because increased adds to the price of drugs, closed borders may in fact increase violent crime. On this front, a prevention program, possibly combined with legalization and taxation, that treats the problem of drug addictions seems a better, cheaper option.

On number 2, I'm not sure how much of a problem slavery and prostitution are. I see no reason that simple law enforcement shouldn't be given this task. Any gaps are likely already there, and the expense of a questionably secure border apparatus for solely this purpose seems inappropriate.

Number 5 isn't really an argument.

Now, it does seem reasonable to fear that completely open borders might trigger a mass-migration that the state wouldn't be able to handle. But there are a number of reasons to doubt this. First of all, if the labor market isn't able to handle them, the immigrants will quickly realize how limited their prospects are. The only alternative is then to either make ends meet through illegal means or seek help from the state. Neither seems a very attractive propositions for prospective immigrants. The idea of relocating hundreds or even thousands of miles to engage in criminal activity seems an odd life choice. What's more, illegal activity entails market pressures of its own. The state is already quite stingy with welfare payments. There seems no reason why it wouldn't still be able to require proof of citizenship for benefits.

A socio-economic and burden that does seem reasonable is the introduction of competition into the labor market. Even assuming that minimum wage laws would still be enforced, numerous occupations would suddenly face an influx of foreign workers. However, language and technical considerations would still give Americans an advantage. The occupations most at-risk would be those in which these forms of human capital would not be required to the same extent. This is the current greatest socio-economic impact of illegal immigration. There is little reason to think that it wouldn't only increase were we to open our borders.

This is where I have the most difficulty finding my own moral perspective. As a college-graduated, credentialed teacher, my job is in no way threatened by immigration. I could see future immigrants receiving credentialing and posing a threat, but that prospect doesn't seem to bother me. I know it may bother some, but I'm not sure whether I feel as though I have some God-given right to teach in America that any other equally-qualified candidate does not, regardless of citizenship. I'm perfectly willing to accept that because I face no real threat from immigrant labor competition, I am missing some possibly persuasively principled argument. But for now I can't foresee any.

As regular readers will note, I have a strong disposition towards viewing socio-economic achievement through the lens of social determinism; I believe the murderer is no more responsible for his actions than the millionaire. Maybe as such, I see no difference between an American citizen and a Mexican citizen. Why should an American have any more right to the American labor market than a Mexican? If there is no existential threat to our entire economy (in which case open borders would become moot as we would all be doomed), the difficulties presented are zero sum: any net cost to American workers presents a net gain to foreign workers.

It is at this point that I think the conversation becomes about abstract notions of nationalism, and what it means to be a citizen. I am entirely utilitarian in that I find the concept of nation-states compelling only in that they make sense in terms of practical governance. Government needs to represent the people for whom it exists. In this way the citizen gains access to democratic rights and privileges. For instance, it would not make sense to allow foreign citizens from around the globe to vote in local elections.

Foreign citizens need not enjoy every single right and privilege of citizens, but to the extent that it is practical for them to do so, they should be allowed them. As I have argued thus far, there appears no practical reason why foreign citizens should not be allowed full access to labor markets. In this way, foreign citizens would not be treated much differently than out-of-state residents. We see no problem with accepting labor competition from any other state in the union. Assuming there are no other social or economic costs, labor competition from foreign countries should be viewed no differently.

Alas, I'm afraid that there exists one last refuge in this argument, and it resides within the nationalistic notion of identity. While many Americans no doubt cling to some form of unconscious bias towards some mysterious cultural quality of "American" that in their mind serves as a line of separation between themselves and non-citizens; that somehow by being an American citizen you are in some way different, and as such entitled to special privileges. Obviously, any dark hatefulness under-girding this attitude is immoral. No human life anywhere on the planet should be considered more worthy than any other. To the extent that nationalism is used as the sole reason for valuing the quality of one life over another, the argument is really based in nothing more than personal greed and selfishness.

As has been pointed out many times before throughout our history, we are a nation of immigrants. Implicit in this conception is the idea that human liberty transcends all boundaries, especially that of the nation state. Inclusion in American society should require nothing more than an agreement to honor its rules and principles. If the only thing that separates an illegal immigrant from a legal one is whether one was given permission from the state to enter, granting that permission to all simply removes that technicality. As I mentioned previously, there is a necessary balance between security and freedom. To the extent that the foreign citizen represents no threat to our security, either economic, social or political, they should be allowed all the freedoms citizens enjoy. And that freedom includes the right to live and work here among us as equals.

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

How to Get Arrested for Being Brown in Arizona

With Arizona's looming implementation of the notorious sb 1070 law, which allows police officers to detain anyone they "reasonably" suspect is an illegal immigrant, the question has been just what "reasonable suspicion" might really mean. The concern for possible civil rights violations revolves around a scenario in which a fully naturalized citizen is considered suspicious, and therefore must then be required to show proof of citizenship. If you happen to forget your wallet, or otherwise fail to present proper ID, arrest and/or detention is implied.

I was able to find some specifics at the Arizona Peace Officer Standards and Training Board website. According to the site, the following are considered valid proof of citizenship:

But the real question still remains: what does "reasonable suspicion" entail? Does eating a burrito count? Thankfully, the APOSTB website offers this help:

So, basically, whatever the fuck the officer feels like pulling out of his ass. "Gee, judge, I just sort of thought those shoes looked kinda.. you know... Mexican. And he appeared to be nervous".

This is really scary.

I was able to find some specifics at the Arizona Peace Officer Standards and Training Board website. According to the site, the following are considered valid proof of citizenship:

- A valid Arizona driver license.

- A valid Arizona nonoperating identification license.

- A valid tribal enrollment card or other form of tribal identification.

- If the entity requires proof of legal presence in the United States before issuance, any valid United States federal, state or local government issued identification.

But the real question still remains: what does "reasonable suspicion" entail? Does eating a burrito count? Thankfully, the APOSTB website offers this help:

FACTORS WHICH MAY BE CONSIDERED, AMONG OTHERS, IN DEVELOPING REASONABLE SUSPICION OF UNLAWFUL PRESENCE

- Lack of identification (if otherwise required by law)

- Possession of foreign identification

- Flight and/or preparation for flight

- Engaging in evasive maneuvers, in vehicle, on foot, etc.

- Voluntary statements by the person regarding his or her citizenship or unlawful presence

- Note that if the person is in custody for purposes of Miranda, he or she may not be questioned about immigration status until after the reading and waiver of Miranda rights.

- Foreign vehicle registration

- Counter-surveillance or lookout activity

- In company of other unlawfully present aliens

Location, including for example:

- A place where unlawfully present aliens are known to congregate looking for work

- A location known for human smuggling or known smuggling routes

- Traveling in tandem

- Vehicle is overcrowded or rides heavily

- Passengers in vehicle attempt to hide or avoid detection

- Prior information about the person

- Inability to provide his or her residential address

- Claim of not knowing others in same vehicle or at same location

- Providing inconsistent or illogical information

- Dress

- Demeanor – for example, unusual or unexplained nervousness, erratic behavior, refusal to make eye contact

- Significant difficulty communicating in English

So, basically, whatever the fuck the officer feels like pulling out of his ass. "Gee, judge, I just sort of thought those shoes looked kinda.. you know... Mexican. And he appeared to be nervous".

This is really scary.

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

Bigotry and the Human Struggle

Julian Sanchez describes the limits to which scientific understanding can assuage our strongly held beliefs. He describes how homosexuality's removal from the DSM, psychiatric manual on mental disease, owed as much to more general social progress than to the scientific evidence.

I’m glad, of course, that we’ve dispensed with a lot of bogus science that served to rationalize homophobia—that’s a pure scientific victory. And I’m glad that we no longer classify homosexuality as a disorder—but that’s a choice and, above all, a moral victory. It ultimately stems from the more general recognition that we shouldn’t stigmatize dispositions and behaviors that are neither intrinsically distressing to the subject nor harmful, in the Millian sense, to the rest of us.

I think this is true. It also explains the persistence of irrational bigotry, as we are seeing coloring (no pun intended) the debate around immigration, social programs, not to mention our black president. People no longer have any scientific, rational justification for their biases, yet they persist. This is best evinced by the person who has no religious or moral problem with gays – but just thinks they’re “gross”.

I think the discussion on racism, sexism, etc. would benefit greatly from a transition from the dogmatic – you “are” or “are not” a bigot – to the nuanced – are your feelings/opinions being informed by social patterns of bias? I think in the past, when bigotry was largely acceptable, the unconscious biases were still there, and just because we decided as a society to make them taboo – the underlying drivers of bias didn’t simply vanish into thin air. The problem now is in identifying ways in which we are still being driven by them.

This is always incredibly dicey. People worked up over illegal immigration always hate any suggestion that racism/ethnocentrism/nativism/etc. might be playing a role in the anger they feel over the issue. This is justified in the sense that no one’s political beliefs should be declared illegitimate from the start, especially if they aren’t explicitly bigoted. But at the same time, there is a historical pattern of bias, built on cultural structures, against poor immigrants. So it is an important conversation to have.

Wikipedia has an excellent list of cognitive biases that provide a nice framework for understanding how this pattern might have historically developed. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_biases. It’s actually a pretty frightening as a look into the frailty of the human psyche. But it’s also disarming in that by explaining why we err, we offer our ego forgiveness.

Of course, the next step is to remain vigilant. And that is a lifelong process that will never achieve perfection. As humans, we are all prone to be led by our fears, angers and prejudices. I think larger social diseases such as bigotry can be thought of as on the same spectrum of behavior as, say, being rude to a store clerk, or acting selfishly towards a roommate or spouse. We are flawed and we are all (hopefully) engaged in an endless struggle to “be better”. The way we do this is always the same: we reflect, we untangle the root of the problem, and then we try to develop the cognitive tools so that should the behavior arise in the future, we have the ability to keep it in check.

I think the discussion on racism, sexism, etc. would benefit greatly from a transition from the dogmatic – you “are” or “are not” a bigot – to the nuanced – are your feelings/opinions being informed by social patterns of bias? I think in the past, when bigotry was largely acceptable, the unconscious biases were still there, and just because we decided as a society to make them taboo – the underlying drivers of bias didn’t simply vanish into thin air. The problem now is in identifying ways in which we are still being driven by them.

This is always incredibly dicey. People worked up over illegal immigration always hate any suggestion that racism/ethnocentrism/nativism/etc. might be playing a role in the anger they feel over the issue. This is justified in the sense that no one’s political beliefs should be declared illegitimate from the start, especially if they aren’t explicitly bigoted. But at the same time, there is a historical pattern of bias, built on cultural structures, against poor immigrants. So it is an important conversation to have.

Wikipedia has an excellent list of cognitive biases that provide a nice framework for understanding how this pattern might have historically developed. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_biases. It’s actually a pretty frightening as a look into the frailty of the human psyche. But it’s also disarming in that by explaining why we err, we offer our ego forgiveness.

Of course, the next step is to remain vigilant. And that is a lifelong process that will never achieve perfection. As humans, we are all prone to be led by our fears, angers and prejudices. I think larger social diseases such as bigotry can be thought of as on the same spectrum of behavior as, say, being rude to a store clerk, or acting selfishly towards a roommate or spouse. We are flawed and we are all (hopefully) engaged in an endless struggle to “be better”. The way we do this is always the same: we reflect, we untangle the root of the problem, and then we try to develop the cognitive tools so that should the behavior arise in the future, we have the ability to keep it in check.

Monday, May 31, 2010

The Dehumanization of "Illegals"

As part of Charlie Rose's ongoing Brain series, the most recent panel discussion involved negative human emotions such as fear and aggression. What stood out to me at one point was during their dialogue on how aggression - a fundamental emotion in all animals - is regulated both by genes and environment. And while early childhood development is very important, and negative experience at an early age can have lasting consequences, that the process is also ongoing through the establishment of social norms. What peers and society deem acceptable provides a framework for one's own emotional barometer.

So in Nazi Germany it was much easier for people to go along with the holocaust when their friends and neighbors seemed OK with it as well. This sort of group think was perpetuated by a cultural and institutional rhetoric that viewed Jews and gypsies as subhuman, notably via language and imagery that compared them to "rats" who were "unclean", "breeding" and "infesting" Europe. This language is common throughout historical examples of genocide. In Rwanda, the Hutu referred to Tutsi as inyenzi, or "cockroaches". This language, apart from the obvious negative association, also simply serves as an efficient way of dehumanizing and objectifying a human being. If a person no longer represents one with whom one might reasonably empathize, it becomes that much easier to deny them rights, marginalize them, or even cause them direct or indirect harm.

It has been common and widely acceptable in America to use the term "illegal" to refer to illegal immigrants, itself a term lending somewhat to human objectification. "Illegals" are often spoken of solely in disparaging terms, i.e. their negative effects on the economy, crime, social spending, wages, and the rule of law itself. The term seems to roll all of that bitterness and anger into one easily digestible phrase. Conspicuously absent from it is any acknowledgment either of the fact that these are real people with real lives, or that a narrative might exist that provides any mitigation of the unlawful behavior.

Combined with a tendency towards ethnic resentment and misinformation, the continued use of dehumanizing language and rhetoric to describe illegal immigrants has lead to increased racial resentment of Hispanics in general. Heidi Beirich, director of research at the Southern Poverty Law center has described a dramatic rise in anti-immigrant hysteria.

So in Nazi Germany it was much easier for people to go along with the holocaust when their friends and neighbors seemed OK with it as well. This sort of group think was perpetuated by a cultural and institutional rhetoric that viewed Jews and gypsies as subhuman, notably via language and imagery that compared them to "rats" who were "unclean", "breeding" and "infesting" Europe. This language is common throughout historical examples of genocide. In Rwanda, the Hutu referred to Tutsi as inyenzi, or "cockroaches". This language, apart from the obvious negative association, also simply serves as an efficient way of dehumanizing and objectifying a human being. If a person no longer represents one with whom one might reasonably empathize, it becomes that much easier to deny them rights, marginalize them, or even cause them direct or indirect harm.

It has been common and widely acceptable in America to use the term "illegal" to refer to illegal immigrants, itself a term lending somewhat to human objectification. "Illegals" are often spoken of solely in disparaging terms, i.e. their negative effects on the economy, crime, social spending, wages, and the rule of law itself. The term seems to roll all of that bitterness and anger into one easily digestible phrase. Conspicuously absent from it is any acknowledgment either of the fact that these are real people with real lives, or that a narrative might exist that provides any mitigation of the unlawful behavior.

Combined with a tendency towards ethnic resentment and misinformation, the continued use of dehumanizing language and rhetoric to describe illegal immigrants has lead to increased racial resentment of Hispanics in general. Heidi Beirich, director of research at the Southern Poverty Law center has described a dramatic rise in anti-immigrant hysteria.

Nativists view Latinos as destroying American society and replacing it with an uncivilized and inferior foreign culture. Many also believe there is a secret plot by the Mexican government and American Latinos to wrest the Southwest away from the United States in order to create “Aztlan,” a Latino nation.In Arizona, senate bill 1070 and its high support among white Americas has already demonstrated a profound willingness to tolerate higher levels of aggression towards Hispanics, historically an ethnic minority. If this sort of dehumanizing rhetoric becomes even more normative, the possibility for increased oppression and even violence seems likely.

Friday, May 28, 2010

Colorblindness

Jamelle Bouie points out that Americans have developed a tendency to rule out anything as racist that doesn't explicitly mention race. He describes ways in which laws can appear "colorblind" but in practice have very racist consequences.

The fact that white people are so willing to go along with this "sacrifice of rights" would be evidence of implicit racial bias. This is exactly the sort of thing that is impossible to prove, yet falls into a larger pattern of not being as tolerant of latinos as other racial/ethnic groups: they need to assimilate, they don't learn the language, they have too many kids, they are lazy, they are criminals, they are a burden on the system, etc.

And that's not even illegal immigrants, who are spoken of in outright hateful terms and accused of things that are extremely unrepresentative. Race theory predicts that the assumed proportionality of crimes increases the more a marginalized a group is. So even if the same number of illegal immigrants steal cars as the rest of the population, when an illegal immigrant does it the crime is assumed to be more representative than it really is. Psychologists refer to this form of cognitive bias as illusory correlation.

You know what really gets me about this whole debate though, is that I’ve yet heard an example of how this law might be prosecuted. For instance, what exactly would constitute “probable cause to believe that the person has committed any public offense that makes that person removable from the United States”, and arrestable without warrant?

I mean, unless you overhear someone say “I am here illegally”, what is probable cause? Can someone be ratted on? Can I call in an anonymous tip on my neighbors? Does that mean anyone can do that to me? And when the cops show up without a warrant they can arrest me unless I show them documentation?

Arizona’s immigration law is obviously not the same as Jim Crow, but it’s animated by the same basic idea of “colorblindness” — if something doesn’t explicitly mention race, then it can’t be racist. And the converse is also true, anything that mentions race is de facto racist, even if it’s designed to ameliorate racial prejudice.He's right to say that the AZ law isn't quite Jim Crow, and I don't think Arizonans (and a majority of white Americans, btw) are looking for ways to discriminate against latinos, while Jim Crow was specifically designed to discriminate against blacks. His main point is that the effect of the law will indeed impact latinos disproportionately - and by effect, we should be clear we're talking about major civil rights violations.

The fact that white people are so willing to go along with this "sacrifice of rights" would be evidence of implicit racial bias. This is exactly the sort of thing that is impossible to prove, yet falls into a larger pattern of not being as tolerant of latinos as other racial/ethnic groups: they need to assimilate, they don't learn the language, they have too many kids, they are lazy, they are criminals, they are a burden on the system, etc.

And that's not even illegal immigrants, who are spoken of in outright hateful terms and accused of things that are extremely unrepresentative. Race theory predicts that the assumed proportionality of crimes increases the more a marginalized a group is. So even if the same number of illegal immigrants steal cars as the rest of the population, when an illegal immigrant does it the crime is assumed to be more representative than it really is. Psychologists refer to this form of cognitive bias as illusory correlation.

You know what really gets me about this whole debate though, is that I’ve yet heard an example of how this law might be prosecuted. For instance, what exactly would constitute “probable cause to believe that the person has committed any public offense that makes that person removable from the United States”, and arrestable without warrant?

I mean, unless you overhear someone say “I am here illegally”, what is probable cause? Can someone be ratted on? Can I call in an anonymous tip on my neighbors? Does that mean anyone can do that to me? And when the cops show up without a warrant they can arrest me unless I show them documentation?

Saturday, May 15, 2010

Fighting Hatred with Compassion

With nativist anti-immigrant fervor in full swing, I felt like I needed some solidarity. So I finally got around to watching Sin Nombre tonight. It's a beautiful, epic, tragic movie, and clearly demonstrates the socioeconomic realities behind illegal immigration.

The main two main arguments for a harsher stance on illegal immigration are economic strain and simple criminality. The first is contentious, but I think one can reasonably say that at current levels, illegal immigrants present - at the least - a zero sum effect on the economy. The non-profit website Factcheck.com has just released a convincing article that shows immigration actually having a positive effect on the economy.

This is obviously going to be a contentious assessment. But surely we can hazard some guess. It isn't as bad as murder. It isn't really stealing from anyone - abstract notions of economic damage aside. It is certainly trespassing in a sense. But then only in the abstract, as no individual is directly bearing the burden on their own property. The real crime can be thought of against the state. Although unlike a traffic citation, or a permit violation, no direct harm - or endangerment is occurring.

Yet whatever the actual crime ends up being, the definitional punishment is almost absurdly harsh: deportation. (Exile, for all intents and purposes). As a punishment, this would be seen as an inappropriate response to all but the most serious crimes. Considering that as a sole offense, an otherwise productive, honest and valuable member of society could be thrown out of the country for nothing more than standing on the wrong side of a line.

The characters in Sin Nombre undertake the journey to America for nothing more than access to its economy. And for this they expose themselves to incredible levels of risk and deprivation. Had they been lucky enough to have enjoyed the social capital to find rarefied social mobility in their home countries - all desperately poor economies - they surely would not have had to make the choice they did. But what kind of ethical judgment did they face? They could have stayed home, facing almost certain wretched poverty for themselves and their families. Or they could have made what seems a minor and abstract transgression by sneaking into America illegally?

Who among us, would not jaywalk daily for such opportunity? Or speed down highways? Or lie on our IRS form? Or act in numerous other abstracted criminal ways in order for a shot at making something of our lives - as well as likely those back home for whom our monthly remittance might mean clean drinking water, money for school, starting a business, or health care?

A third argument against immigration is the one that may be the most powerful as a motivating force, yet will never be spoken or admitted to. It is simple nativism and ethnic bigotry. Like the other arguments it is based in authoritarian fealty to cultural insularity and fealty to authority. It objectifies immigrants in dehumanizing terms like "illegals", and makes no attempt to sympathize with their plight. It makes no attempt to imagine what life might be like in their shoes. It has been around since the founding of the country. It is hypocritical in that it holds certain people to different standards. It favors the majority and those with privilege. It is dangerous: rather than loving or rational, it is fearful and angry.

At this point I'm not sure what there is to do but stand for truth and compassion, and solidarity with our brothers and sisters to the South. We shall prevail. Somehow.

The main two main arguments for a harsher stance on illegal immigration are economic strain and simple criminality. The first is contentious, but I think one can reasonably say that at current levels, illegal immigrants present - at the least - a zero sum effect on the economy. The non-profit website Factcheck.com has just released a convincing article that shows immigration actually having a positive effect on the economy.

Most economists and other experts say there’s little to support the claim. Study after study has shown that immigrants grow the economy, expanding demand for goods and services that the foreign-born workers and their families consume, and thereby creating jobs. There is even broad agreement among economists that while immigrants may push down wages for some, the overall effect is to increase average wages for American-born workers.The second argument, that crossing the border illegally is a crime and justifies harsh measures to "crack down" on lawbreakers, begs the question: what kind of crime is illegal immigration? Every crime has a supposed cost, and presumably we would be able to place it somewhere on a spectrum. If, say, jaywalking presents the most minimal type of crime, with a very slight penalty commensurate with its slight social cost, and murder presents the worst kind of crime, and the punishment reflects its high cost to society, what kind of crime is illegal residence?

This is obviously going to be a contentious assessment. But surely we can hazard some guess. It isn't as bad as murder. It isn't really stealing from anyone - abstract notions of economic damage aside. It is certainly trespassing in a sense. But then only in the abstract, as no individual is directly bearing the burden on their own property. The real crime can be thought of against the state. Although unlike a traffic citation, or a permit violation, no direct harm - or endangerment is occurring.

Yet whatever the actual crime ends up being, the definitional punishment is almost absurdly harsh: deportation. (Exile, for all intents and purposes). As a punishment, this would be seen as an inappropriate response to all but the most serious crimes. Considering that as a sole offense, an otherwise productive, honest and valuable member of society could be thrown out of the country for nothing more than standing on the wrong side of a line.

The characters in Sin Nombre undertake the journey to America for nothing more than access to its economy. And for this they expose themselves to incredible levels of risk and deprivation. Had they been lucky enough to have enjoyed the social capital to find rarefied social mobility in their home countries - all desperately poor economies - they surely would not have had to make the choice they did. But what kind of ethical judgment did they face? They could have stayed home, facing almost certain wretched poverty for themselves and their families. Or they could have made what seems a minor and abstract transgression by sneaking into America illegally?

Who among us, would not jaywalk daily for such opportunity? Or speed down highways? Or lie on our IRS form? Or act in numerous other abstracted criminal ways in order for a shot at making something of our lives - as well as likely those back home for whom our monthly remittance might mean clean drinking water, money for school, starting a business, or health care?

A third argument against immigration is the one that may be the most powerful as a motivating force, yet will never be spoken or admitted to. It is simple nativism and ethnic bigotry. Like the other arguments it is based in authoritarian fealty to cultural insularity and fealty to authority. It objectifies immigrants in dehumanizing terms like "illegals", and makes no attempt to sympathize with their plight. It makes no attempt to imagine what life might be like in their shoes. It has been around since the founding of the country. It is hypocritical in that it holds certain people to different standards. It favors the majority and those with privilege. It is dangerous: rather than loving or rational, it is fearful and angry.

At this point I'm not sure what there is to do but stand for truth and compassion, and solidarity with our brothers and sisters to the South. We shall prevail. Somehow.

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Ethnic Studies and Marginalization

Arizona recently passed a law that among other things aims to remove ethnic studies courses from high schools. House Bill 2281:

Obviously, to anybody who has actually taken an ethnic studies course, this language in no way describes them. Yet lest anyone doubt that ethnic studies programs are indeed the target, according to the Arizona Daily Star:

People sometimes argue that, were ethnic studies programs to include white studies, they would be seen as racist. But this is a misunderstanding of the purpose of ethnic studies: to study the historical issues of oppressed groups. At the college level, this also includes women and gays. The reason it is important to study our interaction with these groups is so that we, as a society, may come to terms with our tendency to mistreat each other. This is a real phenomenon, and deserves attention.

To the extent that it emphasizes ethnic identity - what is wrong with that? As a straight white man I have no need to assert "pride" because it is inherent in the privileges I enjoy by default - society affirms my identity every day. The historical oppression of groups has occurred precisely because of their marginalization and disempowerment. What ethnic studies classes are doing is at worst simply adding what has been taken away, and at best providing us all an insight into how social structures and behavior patterns we take for granted ultimately result in the loss of freedoms for others. We are a nation rich in ethnic diversity and we ought to treasure the opportunity to learn to promote equality for all.

I could only find a piece of it, but Chris Rock does a great bit on the concept of false equivalency and social power structures.

Prohibits a school district or charter school from including in its program of instruction any courses or classes that:

•Promote the overthrow of the United States government.

•Promote resentment toward a race or class of people.

•Are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group.

•Advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.

Obviously, to anybody who has actually taken an ethnic studies course, this language in no way describes them. Yet lest anyone doubt that ethnic studies programs are indeed the target, according to the Arizona Daily Star:

State schools chief Tom Horne, a Republican running for Attorney General, says the district's ethnic studies program promotes "ethnic chauvinism" and racial resentment toward whites.

People sometimes argue that, were ethnic studies programs to include white studies, they would be seen as racist. But this is a misunderstanding of the purpose of ethnic studies: to study the historical issues of oppressed groups. At the college level, this also includes women and gays. The reason it is important to study our interaction with these groups is so that we, as a society, may come to terms with our tendency to mistreat each other. This is a real phenomenon, and deserves attention.

To the extent that it emphasizes ethnic identity - what is wrong with that? As a straight white man I have no need to assert "pride" because it is inherent in the privileges I enjoy by default - society affirms my identity every day. The historical oppression of groups has occurred precisely because of their marginalization and disempowerment. What ethnic studies classes are doing is at worst simply adding what has been taken away, and at best providing us all an insight into how social structures and behavior patterns we take for granted ultimately result in the loss of freedoms for others. We are a nation rich in ethnic diversity and we ought to treasure the opportunity to learn to promote equality for all.

I could only find a piece of it, but Chris Rock does a great bit on the concept of false equivalency and social power structures.

Monday, March 22, 2010

Who Are We?

Judith Butler is a Maxine Elliot Professor in the Departments of Rhetoric and Comparative Literature at University of California Berkeley. In a recent interview she discusses her latest book, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable?

A fierce critic of war, or at least our seeming endless tolerance for it, she has harsh words for Obama, who she says has not nearly been the critic of war she would have liked him to be. But, as a philosopher, she's more interested in getting at deeper questions, and tries to see how we end up where we do.

I think before entering warfare one needs to ask oneself whether, if it were to take place in their own country, they would fight in the same way. If the answer is yes, then there is no moral hypocrisy. But as soon as you begin to think of the lives of inhabitants of some far off land as less meaningful than those of your countrymen, you've begun to lose your humanity.

A similar thought occurred to me today, albeit on a much different subject. We are putting an addition on our house, which is about 2 hours from the Mexican border. Many in our community are migrant workers, some legal, some not. Well, a couple of Mexicans came to my door, speaking very poor English, and offered a bid to stucco the exterior walls. I thanked them for the offer, and said I'd give their card to the contractor - who as it happens has at least one undocumented worker in his employ.

I wondered how I felt about profiting from illegal labor - certainly their wages would be a drag on those of naturalized citizens. How would I like it if an undocumented Mexican was able to compete for my job as a teacher? And what if that meant a substantial pay cut?

I'm not sure I would have a problem with it. I mean, sure, I want to get paid as much as I can. But what right do I have over anyone else, if they can the do the same job for less? What right do I have, just because the uterus I came out of 34 years ago just happened to have been a US citizen? We only need to go a handful of uteruses back and my family tree would have been the ones doing the displacement.

Nationalism, while a useful and nostalgic concept, can lead to the most base sort of inhumanity and objectification. What other tendency of human thought can be so soaked in the blood of injustice than provincial arrogance and arbitrary righteousness? Such despicable, beast-like behavior. Every man for himself, this is my lifeboat, get out. The post-hoc rationalizations fill endless volumes of rhetoric down through the centuries. They trickle slowly through the days like sticky-saccharine.

Looking back, we've come so far. But we have so far to go still.

A fierce critic of war, or at least our seeming endless tolerance for it, she has harsh words for Obama, who she says has not nearly been the critic of war she would have liked him to be. But, as a philosopher, she's more interested in getting at deeper questions, and tries to see how we end up where we do.

Along with many other people, I am trying to contest the notion that we can only value, shelter, and grieve those lives that share a common language or cultural sameness with ourselves. The point is not so much to extend our capacity for compassion, but to understand that ethical relations have to cross both cultural and geographical distance. Given that there is global interdependency in relation to the environment, food supply and distribution, and war, do we not need to understand the bonds that we have to those we do not know or have never chosen? This takes us beyond communitarianism and nationalism alike. Or so I hope.

I think before entering warfare one needs to ask oneself whether, if it were to take place in their own country, they would fight in the same way. If the answer is yes, then there is no moral hypocrisy. But as soon as you begin to think of the lives of inhabitants of some far off land as less meaningful than those of your countrymen, you've begun to lose your humanity.

A similar thought occurred to me today, albeit on a much different subject. We are putting an addition on our house, which is about 2 hours from the Mexican border. Many in our community are migrant workers, some legal, some not. Well, a couple of Mexicans came to my door, speaking very poor English, and offered a bid to stucco the exterior walls. I thanked them for the offer, and said I'd give their card to the contractor - who as it happens has at least one undocumented worker in his employ.

I wondered how I felt about profiting from illegal labor - certainly their wages would be a drag on those of naturalized citizens. How would I like it if an undocumented Mexican was able to compete for my job as a teacher? And what if that meant a substantial pay cut?

I'm not sure I would have a problem with it. I mean, sure, I want to get paid as much as I can. But what right do I have over anyone else, if they can the do the same job for less? What right do I have, just because the uterus I came out of 34 years ago just happened to have been a US citizen? We only need to go a handful of uteruses back and my family tree would have been the ones doing the displacement.

Nationalism, while a useful and nostalgic concept, can lead to the most base sort of inhumanity and objectification. What other tendency of human thought can be so soaked in the blood of injustice than provincial arrogance and arbitrary righteousness? Such despicable, beast-like behavior. Every man for himself, this is my lifeboat, get out. The post-hoc rationalizations fill endless volumes of rhetoric down through the centuries. They trickle slowly through the days like sticky-saccharine.

Looking back, we've come so far. But we have so far to go still.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

Economics of Illegal Immigration

One of the arguments you hear against illegal immigration, or at least, as an imperative to defend against it as if it were some great threat to the national economy, is that it has a downward effect on wages.

It’s important to be skeptical about economic assumptions. Even experts get overwhelmed, and most of us simply rely on ideology for the gray areas.

Unfortunately, political points are frequently made on the basis of very simplistic and often entirely faulty premises. The classic example is the comparison of the national economy to one’s household budget. If we find ourselves struggling to pay the rent, we need to cut back on spending. Yet Keynesian economic theory tells us that often times the very best thing to do is for the government to actually increase spending so as to "stimulate" a stagnant economy. Even this is is a dramatic simplification, but the larger point remains that things are not as simple as they often appear on the surface.

With immigration, the story is no less complex. It might seem reasonable to imagine that illegal immigrants, willing to work for less, push wages down. But it is just as reasonable to imagine that this increased productivity pushes other wages up – if a dishwasher can be had for less, more might be spent on the chef, etc.

In the end, all we really have (those of us lacking a serious background in economics), is our philosophical judgment and where it finds adherence among credible experts in the field. This always presents a range, but is at least a reasonable hook upon which to hang our hat.

It’s important to be skeptical about economic assumptions. Even experts get overwhelmed, and most of us simply rely on ideology for the gray areas.

Unfortunately, political points are frequently made on the basis of very simplistic and often entirely faulty premises. The classic example is the comparison of the national economy to one’s household budget. If we find ourselves struggling to pay the rent, we need to cut back on spending. Yet Keynesian economic theory tells us that often times the very best thing to do is for the government to actually increase spending so as to "stimulate" a stagnant economy. Even this is is a dramatic simplification, but the larger point remains that things are not as simple as they often appear on the surface.

With immigration, the story is no less complex. It might seem reasonable to imagine that illegal immigrants, willing to work for less, push wages down. But it is just as reasonable to imagine that this increased productivity pushes other wages up – if a dishwasher can be had for less, more might be spent on the chef, etc.

In the end, all we really have (those of us lacking a serious background in economics), is our philosophical judgment and where it finds adherence among credible experts in the field. This always presents a range, but is at least a reasonable hook upon which to hang our hat.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)