Kevin Drum writes on liberal sneering.

I'm not here to get into a fight with Krugman, but come on. Sure, the right-wing media fans the flames of this stuff, but is there really any question that liberal city folks tend to sneer at rural working-class folks? I'm not even talking about stuff like abortion and guns and gay marriage, where we disagree over major points of policy. I'm talking about lifestyle.

I think this is super important, and something I've been interested in for a long time. What is taste? What does "cheese" really mean. What does it mean to sneer? And it is a central theme of the Trump election.

On the one hand, I do sneer at cheesy things, because they are cheesy. Is this wrong? Does sneering at things imply a value judgement about the person? If I dislike Coors beer, can I sneer at it without being said to sneer at the person who likes it? Is it because by extension people who like cheesy things without awareness are diminished, deemed inferior? Of course we can all have preferences, but the definition of sneer does mean "to look down on".

Knowledge is central here; awareness. Without it, you are ignorant by definition. Yet it isn't merely awareness but the status associated with certain forms of knowledge. Uneducated people have a ton of knowledge that I do not - mechanics, carpenters, businessmen, etc. Yet if they wear fannypacks, watch wrestling and buy sweatpants at Walmart they are living a cheesy lifestyle. So, the issue is cheese.

The dictionary definition of cheesy is that it is slang for something that is of inferior quality, poorly made, or cheap. But there is more too it. There is a sense in which the term refers to a lack of education on specific social standards. These are arbitrarily defined according to a critical consensus of what is valuable at a given time. Some things, like fashion, of course change rather rapidly, and the standards evolve. As Heidi Klum states in her tagline for the TV show Project Runway (which my wife and daughters adore),

"One day you're in. And one day you're out."

As long as you are a willing participant in the specific cultural practice of following fashion, and place value on what the arbitrary standards are, you accept the terms of engagement. However, many - possibly most, people aren't so interested in fashion. Or, find it difficult to keep up with. They just kind of go along with what they find on the rack.

But it comes down to one's personal cultural milieu. Different social circles have different associated fashions - almost uniform-like, in a sense. You have the butch Lesbians with their jeans and vests. You have the preppy boys with their izods and loafers. You have the metrosexuals with their perfectly groomed facial hair arrangements. Rural women with modest denim blouses and blowdried bangs. Artsy hipsters with random t-shirt advertisements and victorian mustaches. Dockworkers with baseball caps and practical, tinted sunglasses. There is obvious social benefit in these groups to align oneself with the mutually agreed-upon standard. When in Rome.

But "cheesy" is something different. It seems primarily defined by knowledge, and a value ranking. To agree to the terms is to make a value judgement. And in order to make this judgement, one must first accept the premise that there are specific social standards. One can understand something to be "cheesy", and decide that it is unimportant, and embrace the cultural practice anyway. Indeed, a common way to flout social convention is to engage in "cheesy" activities with the explicit understanding that these activities are "cheesy". This is an especially productive move when the practice deemed "cheesy" had been placed off-limits as a low-value practice, and yet is actually quite objectively enjoyable. I myself engage in this when I listen to Linda Rondstand and Aaron Neville during my drive to the movie theater to watch a blockbuster action film, afterwards dining on fast food before returning home to play videogames. Of course, I "know" that this is all cheesy, and so in certain circles you have the post-modern phenomenon of embracing low-value social practices, such as the iconic Pabst beer (which tastes like piss) in Portland, OR.

Yet what once is learned can not be unlearned. There are better beers, with more flavor. There is better music, relying on less cliche structure and lyricism. There are better movies which explore larger issues of human experience with innovation and craft. There is cuisine that engages more senses than salt, sweet and fat. There are leisure activities that enrich one's personal repertoire of experience and expression than lining up an x and y axis and flipping buttons to pumping music.

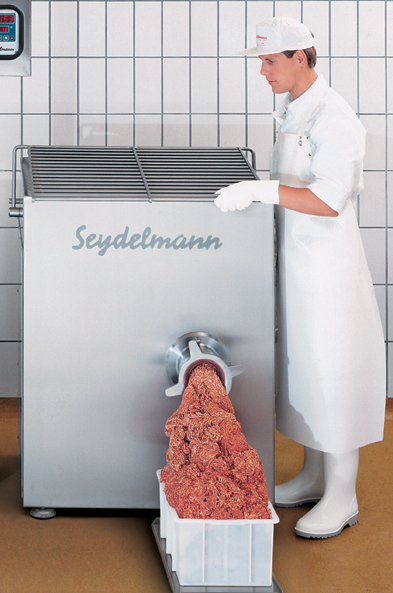

So why engage in one activity versus another? How ought one spend one's time? What kind of a society does one want? Does one believe in the arts, in innovation, in creativity, rather than cheap, inexpensively produced "popular" culture that hews tightly to well-established and low-risk endeavor? Sweat pants at Wal Mart, slim jims and the Bachelorette are cheap and get the job done. But what is their place in the larger scale of human history?

Donald Trump likes gold decor. It is shiny, representative of money, and so ostensibly he believes the more of it the better. Of course, this is an incredibly cliched and superficial standard by which to judge quality. It demonstrates that he is unaware of the complex standards by which one might judge the value of decor. This isn't necessarily a bad thing - many people are similarly unknowledgeable (I've chosen not to use the term

ignorant to avoid its negative connotation, despite personally finding nothing wrong with being ignorant of something there is no need to be knowledgeable of. However, I concede that is the whole point of this post). If Trump merely had brown sofas, or had hired an interior designer, no one would notice. But instead, he actively went out and engaged in a demonstration of what he personally finds attractive. He thus embarrassed himself by demonstrating for all to see not just his ignorance (now the term seems to fit?), but his desire for others to see just how wealthy he is in a very obvious way, akin to wallpapering his home with hundred dollar bills. Surely there are other ways of telegraphing wealth - rich people do it all the time. Yet what he did, more than anything else, was actually telegraph his ignorance of social practices, of taste.

Is taste OK? Is it OK to make value judgements on cultural practices? To hear some, such a question is almost tasteless itself. Of course it isn't OK! It is snobbish, bourgeoise. And yet this is of course ridiculous. We all have taste. We all have preferences. We can all appreciate that taste is ultimately about craft, about many people over time working to develop a repertoire of cultural creation. This can only be done by valuing certain things over others. Anyone who has view art, watched a movie, listened to music, or picked out a pair of pants has engaged in the appreciation of taste. Taste is about the creation of fulfilling experiences. Like any other craft, the production of these experiences requires time and expertise.

Everyone can appreciate craft. And here is where the taste divide might appear. No one turns their nose up at the ability of someone to build something useful. Its importance is immediately apparent. Sewer pipes, bridges, walls, stairs, roads, delivering mail, fixing cars, growing food. These are all working class endeavors. And there is a product that is fundamentally useful to all. A better bridge is safer, a better sewer pipe is more efficient, a better crop feeds more people. Saying one is better than the other is self-evident.

Not so with taste. The difference between a classical musician and a popstar, or a difficult work of art that requires a complex understanding of context and a very accurate image of someone doing something that looks fun, is not about function. The very definition of "pop" comes from mass-appeal. But it also almost always means somehow cheaper, less developed, and - often - more difficult to enjoy.

Whether valid or not, a certain sort of class resentment does seem at play. A traditional definition of civilization is the ability of a society to produce enough surplus food to afford to support someone whose only job is arts and entertainment. Class hierarchies have always bred resentment and distrust. To the extent that one job is easier than another, or at least appears to be, it will be resented. So much more so if the job is deemed higher-status.

The working-class, those who make their living with their hands, might indeed feel resentment towards those who make their living indoors, away from the grime, without elbow-grease. And imagine if while these non-working class individuals were off in universities, they gained not only the ability to gain high-wage jobs, but also gained an ability as well to gain high-status tastes - art, literature, philosophy. And more recently, notions of what is "politically correct". And imagine them then coming back home and no longer appreciating your low-class, uneducated and low-status cultural preferences.

At this point, do they really need to "sneer" for the resentment to be felt? I'm actually of the opinion that there isn't actually that much sneering going on. As Drum mentions towards the end of his post, working-class can sneer too. Isn't really just about how you treat people. You can have preferences, but you don't need to sneer. But there are cultural resentments, especially when it feels like you can't get ahead, even if this is isn't because of the educated, but rather an economic and social system that isn't very good at giving everyone a fair chance.

Donald Trump has nothing to offer but trickle down theory, which is cold comfort. Instead he and his right-wing nationalist talk-radio ilk sell a narrative that the real problem is pointy-headed, educated liberal fascists (try replacing "liberal" with Jew sometime and historical resonance gets creepy). For whatever reason it has obviously been working. His tackiness is his credentials. The more he attempts to gain status without knowing the difference, the more relatable he is. He's ridden into office on a wave of resentment of the elite, a tide of Coors beer and bad TV. He could walk out onto 5th avenue in a fanny pack and people would cheer.