John McWhorter and Glen Loury did a diavlog recently where both expressed the view that the black community needs to take responsibility for its own failure. Mc Whorter even went so far as nearly advocating an entire federal pullout of all programmatic help. The metaphor they both used was one in which a vehicle strikes a pedestrian. No matter how much the vehicle was in the wrong, at the end of the day the pedestrian needs to want to walk if he is ever actually going to. The driver can't "make them do it". Apparently this originated from a book by Amy Waxman that McWhorter praised.

I'm not sure how to express how angry this sentiment makes me.

The metaphor is flawed for this reason: social determinism is a fact, and it is very driven by government policy. Sure, it is of course true that black families are failing and perpetuating poverty. But it is not as if there is some switch that Cosby, McWhorter or anyone else can throw that can change culture either. Black families would succeed if they knew how. The problem is that they lack the human capital. Wax's argument amounts to "leaving them alone and letting them sort it out for themselves".

I'm sorry, but as a former teacher of low-income children, that attitude just makes me want to scream. Sure the pedestrian needs to want to walk, but who doesn't. It is human nature to want to walk. Blacks aren't failing because they don't want to succeed. They are failing because they don't have the ability. And what is keeping them from gaining that ability stems from the original accident.

If we want to really flesh out the metaphor, in a way that is line with our current understanding of how human development and learning works, we need to start by addressing the reasons for black failure. We can do this in a general way by looking at statistical correlations between features that align with success. So, the first is parent education. The higher the education level of the parent the better they tend to do. There are reasons for this, but we'll leave it at that for now. Second is income. A big part of this is going to be peer grouping in education - poor kids have poor classmates. Third is intact families. McWhorter and Loury began with this in the first place! The reasons for why this matters are also well known. Fourth is drugs. Pretty obvious. From here we can go in any number of directions, from parent incarceration to abuse to environmental toxicity to parenting skills.

The effects of all of all this do not magical begin when the child turns 18, and becomes an "adult" with so-called free will. No, they begin at birth - actually in the case of some of them they begin to have an effect in utero. In the first five years of the child's life, they are completely surrounded in a cocoon of all these risk factors. Only when they reach Kindergarten do they hopefully have a chance at larger social remelioration. Of course, by this time they are far behind their non-at-risk peers academically, emotionally and cognitively. And the process just compounds itself as they labor through the years, suffering a life of routine humiliation that they may not understand but intuit clearly. And once they reach sexual maturity, they begin having babies, and the cycle repeats.

That is the accident. The pedestrian is lying bleeding on the pavement at age... pick one - 6 months, 2 years, 5 years, 16 years, 25 years, 45 years. They are where they are in life because of who their parents were, what community they came from, what brain they were born with, and beyond that what kind of luck they found. If "choice" had anything to do with it, you would see a random distribution of success across demographics. There would be no minority achievement gap or uneven incarceration rate. To the degree that it persists, it is because we allow it to. I have had students who were mothers at 16 and let me tell you, if you think their baby has any say in whether they "want" to succeed you are fooling yourself.

Now, maybe there is nothing we can do. Maybe trying to "help" will only make things worse. For social determinism to be true it doesn't require that we have the answers. But fortunately for us, we actually do have the answers. There are evidence-based programs that work. It is possible for money to spent on targeted services that provide any child with the human capital needed to succeed. For some, it may be relatively inexpensive - a few after schools classes here, a summer camp there. For others it may be very expensive, with nurse home visits and occupational therapy, behavior-modification counseling for the whole family, small class sizes and mentorships. The problem isn't that the black community isn't choosing to help themselves. That's at best a meaningless red-herring, and at worst a convenient cop-out. The problem is that we aren't choosing to help them.

A bastard's take on human behavior, politics, religion, social justice, family, race, pain, free will, and trees

Friday, April 30, 2010

The Case of the Boring Porn

Something that has likely bedeviled couples since, well at least the mass production of photographs, is the fact that women just aren't as interested in pornography as men. I have yet to meet a man who is not turned on by pornographic imagery. The statistics for porn consumption certainly backs this up.

There have been many explanations for why this difference in sexual excitation might exist. Maybe men are expressing an unconscious misogyny. Taught to objectify women, they use them as props in their sexual fantasies. But this analysis is very abstract, and relies heavily on a Freudian interpretation to buttress its political claim of gender oppression. The popularity of porn consumption by gay men would seem to argue against this theory. One would have to claim that gay men have internalized misogyny and then incorporated it into their objectification of other males.

Maybe men are just objectifiers by nature, while women are more relationship oriented. Women tend to prefer the romance of seduction, something difficult to express in pornographic imagery, more suited to the written word. The extremely graphic nature of most porn - the close-up shots of penetration and thrusting, seem almost clinically devoid of any pretense of emotion aside from carnal lust. This would make sense from the evolutionary psychology view of men as spatially oriented hunters, and women as relationship oriented mothers and gatherers.

But what if it simply comes down to a feature of biology and culture? The penis, especially when uncircumsized, is designed for rapid climax during intercourse. Men typically reach orgasm in 5-10 minutes - much to the dismay of their thus unsatisfied female partners. Women generally take twice as long. Of course, this has everything to do with the quality of lovemaking. Female anatomy makes orgasm via intercourse alone much more difficult because the act of penetration stimulates the male more than the female. This discrepancy can be overcome, but only through creativity and experience.

So what might the physical anatomy of men and women have to do with porn? Well, it may have something to do with the anatomy of the brain. Sexual orgasm is probably the most pleasurable state one can achieve. It makes sense, then, that the brain would learn to associate that feeling with imagery. This has been found to be the case with addiction, where images of drugs are associated and with increased desire. Anyone who has ever stopped smoking will tell you that just being around people who are smoking will trigger cravings. We are learning that the obesity epidemic may be linked directly to this phenomenon - where an environment of copious consumption, mainly through advertising, is fueling overeating. Maybe the pleasure response of climax is tied more closely to association in men than women, as the lag in climax time diminishes associative effects.

In this way the male orgasm is likened to the effects of nicotine, crack, or a cheeseburger, with the associative response triggering cravings in proportion to the immediacy and intensity of the sexual experience. If the dynamic is extended to the female orgasm, taking twice as long to achieve - if at all, it seems logical that the associative response would not be as powerful. We know that women can have associations just as powerful as men when addicted to drugs or food. And we don't generally think of these things as being "objectified", but they in fact are. But what if women didn't experience the same level of pleasure from those activities as men? When a men and women both see a billboard for a cheeseburger, they can imagine - on some level - its salty, fatty juices dripping down their gullet. And they know that in a few minutes that pleasure can be theirs. But what if women's experience of cheeseburger bliss was something less than guaranteed?

I'm not aware of any study having been done on this. But I think it would be very interesting. The hypothesis would be that when stimulated to orgasm with the same degree of consistency and immediacy of men, women should show an increased associative response to pornographic imagery. Of course, there are other cultural mitigating factors, such as gender identity or sexual narrative. But it would be interesting to see if there might be a link to this mysterious phenomenon.

There have been many explanations for why this difference in sexual excitation might exist. Maybe men are expressing an unconscious misogyny. Taught to objectify women, they use them as props in their sexual fantasies. But this analysis is very abstract, and relies heavily on a Freudian interpretation to buttress its political claim of gender oppression. The popularity of porn consumption by gay men would seem to argue against this theory. One would have to claim that gay men have internalized misogyny and then incorporated it into their objectification of other males.

Maybe men are just objectifiers by nature, while women are more relationship oriented. Women tend to prefer the romance of seduction, something difficult to express in pornographic imagery, more suited to the written word. The extremely graphic nature of most porn - the close-up shots of penetration and thrusting, seem almost clinically devoid of any pretense of emotion aside from carnal lust. This would make sense from the evolutionary psychology view of men as spatially oriented hunters, and women as relationship oriented mothers and gatherers.

But what if it simply comes down to a feature of biology and culture? The penis, especially when uncircumsized, is designed for rapid climax during intercourse. Men typically reach orgasm in 5-10 minutes - much to the dismay of their thus unsatisfied female partners. Women generally take twice as long. Of course, this has everything to do with the quality of lovemaking. Female anatomy makes orgasm via intercourse alone much more difficult because the act of penetration stimulates the male more than the female. This discrepancy can be overcome, but only through creativity and experience.

So what might the physical anatomy of men and women have to do with porn? Well, it may have something to do with the anatomy of the brain. Sexual orgasm is probably the most pleasurable state one can achieve. It makes sense, then, that the brain would learn to associate that feeling with imagery. This has been found to be the case with addiction, where images of drugs are associated and with increased desire. Anyone who has ever stopped smoking will tell you that just being around people who are smoking will trigger cravings. We are learning that the obesity epidemic may be linked directly to this phenomenon - where an environment of copious consumption, mainly through advertising, is fueling overeating. Maybe the pleasure response of climax is tied more closely to association in men than women, as the lag in climax time diminishes associative effects.

In this way the male orgasm is likened to the effects of nicotine, crack, or a cheeseburger, with the associative response triggering cravings in proportion to the immediacy and intensity of the sexual experience. If the dynamic is extended to the female orgasm, taking twice as long to achieve - if at all, it seems logical that the associative response would not be as powerful. We know that women can have associations just as powerful as men when addicted to drugs or food. And we don't generally think of these things as being "objectified", but they in fact are. But what if women didn't experience the same level of pleasure from those activities as men? When a men and women both see a billboard for a cheeseburger, they can imagine - on some level - its salty, fatty juices dripping down their gullet. And they know that in a few minutes that pleasure can be theirs. But what if women's experience of cheeseburger bliss was something less than guaranteed?

I'm not aware of any study having been done on this. But I think it would be very interesting. The hypothesis would be that when stimulated to orgasm with the same degree of consistency and immediacy of men, women should show an increased associative response to pornographic imagery. Of course, there are other cultural mitigating factors, such as gender identity or sexual narrative. But it would be interesting to see if there might be a link to this mysterious phenomenon.

Lying About Bailouts

Republicans have made a lot of political hay over the claim that the bank bailouts never posed systemic risk. They don't spend a lot of time providing an argument for this claim - most likely because it's so indefensible. They just skip to the logical conclusion that anyone who supports bailouts wants to waste taxpayer money buy giving it to greedy Wall Street. This also plays into the idea that Democrats don't want anyone to ever fail because they are, well, pansies.

Of course, TARP was enacted by Bush, but he can be written off as not a "true believer". The important thing is that future bailouts will never be necessary because there is no such thing as systemic risk.

Jon Chait argues that systemic risk would always require a bailout, and any sane administration - whether Republican or Democrat - wouldn't hesitate to come to the rescue. Yet by sticking to the dishonest claim that systemic risk can't happen, Republicans get to have their cake and eat it too:

This is no different than the Republican tactic on most issues: take a false or dubious premise and run with it.

Republicans kind of lucked out on the timing of the crisis. Because TARP happened so close to the inauguration, they managed to sell idiots the lie that Obama was responsible for the bailout. If this had happened even a year earlier, it would have been a lot tougher.

Of course, TARP was enacted by Bush, but he can be written off as not a "true believer". The important thing is that future bailouts will never be necessary because there is no such thing as systemic risk.

Jon Chait argues that systemic risk would always require a bailout, and any sane administration - whether Republican or Democrat - wouldn't hesitate to come to the rescue. Yet by sticking to the dishonest claim that systemic risk can't happen, Republicans get to have their cake and eat it too:

The only answer to the dilemma is to try to prevent systemic failure from happening in the first place, which is the purpose of financial regulation. But this is the genius of the "bailout bill" charge. You can't honestly promise that any regulation, however well-designed, can guarantee that no bailout will ever happen again. And when you try to address the "bailout bill" charge on its own loopy terms, you wind up lending it credence.

This is no different than the Republican tactic on most issues: take a false or dubious premise and run with it.

- Global warming - doesn't exist so Democrats are just trying to scrounge up tax revenue.

- Immigration - it's an existential threat so we need to limit rights and expend vast resources, and Democrats actually favor illegal immigration.

- Supply side economics - cut taxes on the rich and slash spending because the increased growth will ultimately increase tax revenues.

- The stimulus - Keynes who?, Democrats are recklessly spending and that's just what they do.

- The bailouts - institutions didn't pose systemic risk so bailing them out was simply a handout, a socialist takeover of the banking industry even.

Republicans kind of lucked out on the timing of the crisis. Because TARP happened so close to the inauguration, they managed to sell idiots the lie that Obama was responsible for the bailout. If this had happened even a year earlier, it would have been a lot tougher.

Thursday, April 29, 2010

Leadership Issues

When businesses fail - we don't blame the workers, we blame the CEO.

When the military fails - we don't blame the soldiers, blame the generals.

When Governments fail - we don't blame the staff, we blame the representatives.

But when schools fail, who do we blame? The teachers.

Now, obviously this is simplistic. The problem with most failing schools is a variety of things. It includes teachers. It includes teachers. Most of all, however it includes parents. But at the end of the day, a school lives or dies by its leaders. They set the tone. They establish culture. They hold people accountable. They inspire people. They work with students, teachers and families alike to develop a sense of genuine purpose and community.

The Quick and the Ed points to a new study that backs this up. Their take:

When the military fails - we don't blame the soldiers, blame the generals.

When Governments fail - we don't blame the staff, we blame the representatives.

But when schools fail, who do we blame? The teachers.

Now, obviously this is simplistic. The problem with most failing schools is a variety of things. It includes teachers. It includes teachers. Most of all, however it includes parents. But at the end of the day, a school lives or dies by its leaders. They set the tone. They establish culture. They hold people accountable. They inspire people. They work with students, teachers and families alike to develop a sense of genuine purpose and community.

The Quick and the Ed points to a new study that backs this up. Their take:

Principals affect a range of outcomes, including teacher satisfaction, parents’ perceptions of school quality, and the academic performance of the school. How to ensure a good principal? A principal’s effectiveness depends on their level of experience, their sense of efficacy on certain tasks, and their use of time to manage the range of responsibilities they face. Where are the good principals? Not in poor or poor-performing schools, at least not as a rule. Principals that demonstrate the skills and experience related to effectiveness are less likely to be working in these schools.

Information and Society

Matt Yglesias ponders the regulation of salty foods:

This is about information. The strong libertarian believes that if it is possible for one to have the knowledge necessary to make a decision, they must be held accountable for the decision. So for instance, it is obvious that smoking crack is bad for you. If you do it, you have only yourself to blame. Basically, information is liberty.

The problem non-libertarians generally have isn’t that we don’t believe in liberty – it’s that we are more skeptical that information is so free. We see evidence of people on a daily basis making decisions that, were they to have had the information, they would not have otherwise. There is a large amount of evidence for this.

This explains why the non-libertarian is skeptical of business: to a large degree, business often profits from an imbalance in information. The whole Goldman Sacks fiasco is predicated on just this sort of dynamic. On a small scale, you can see this happen when the auto mechanic charges too much for a service because the customer doesn’t understand the procedure or has no knowledge of cheaper service elsewhere.

Libertarians are generally thought of as utopians because there is obviously not a perfect distribution of information – nor will there ever be.

Now, taking things to the next level, we ought to ask, “What is information?”. Because when one makes a decision, they are not only making a rational decision, but also acting from countless hidden, unconscious impulses. The advertising industry is predicated on this fundamental truth about human nature. Businesses hire advertisers not only to selectively provide specific information to consumers, but to actively craft messages that exploit the human unconscious. The fact that Tylenol exists is a testament to this fact: despite the generic being the exact same product, and sitting right beside Tylenol in the pharmacy aisle, Tylenol is a very profitable brand.

So the libertarian not only must deal with citizens not having access to equal levels of literal information, but unconscious and emotional information as well. The two together are what social scientists refer to as “human capital”.

Both of these together conspire to create a world in which the libertarian assumption of liberty through information really amounts to a world in which liberty is very unequally distributed. The coherent intellectual and moral response to this is to try and structure society in a way that maximizes information. Intellectually dishonest libertarians will peddle the claim that this social structure is one in which government is highly limited and markets are thus free.

But the obvious answer is that not only will information become even more stratified, but so too will the means of action. Wealth and information are power. Those who have more will always have an advantage. As we have seen throughout history, if left unchecked power will accrete. Liberty is eroded. The non-libertarian’s response is thus to strategically erect governmental bulwarks against this natural process.

Of course, the opposite of the libertarian, the communist, will end up doing much the same thing. Although instead of power accumulating among business oligarchs it accumulates in the state. Interestingly, both ideologies claim to be on “the side of liberty”. Yet if liberty is both information and the ability – conscious or otherwise – to act on information, neither system provides it. In fact, both actively destroy it. The answer then, which most responsible democracies have adopted, is a mixture of both market freedom and government regulation. The question is not whether regulation or markets are bad, but how you do them.

Clearly, the goal here is to get people to eat less salt. And it’s true that once we accept that concern for public health is a legitimate public concern we are opening the door in principle to a lot of government activity. On the other hand, even though a lot of people have libertarian instincts about novel paternalistic measures relatively few people have a consistent view in the other direction. Government policy encourages vaccinations against infectious diseases and you never see anyone agitating for the right of poor people to use SNAP to buy tax-free cigarettes.

This is about information. The strong libertarian believes that if it is possible for one to have the knowledge necessary to make a decision, they must be held accountable for the decision. So for instance, it is obvious that smoking crack is bad for you. If you do it, you have only yourself to blame. Basically, information is liberty.

The problem non-libertarians generally have isn’t that we don’t believe in liberty – it’s that we are more skeptical that information is so free. We see evidence of people on a daily basis making decisions that, were they to have had the information, they would not have otherwise. There is a large amount of evidence for this.

This explains why the non-libertarian is skeptical of business: to a large degree, business often profits from an imbalance in information. The whole Goldman Sacks fiasco is predicated on just this sort of dynamic. On a small scale, you can see this happen when the auto mechanic charges too much for a service because the customer doesn’t understand the procedure or has no knowledge of cheaper service elsewhere.

Libertarians are generally thought of as utopians because there is obviously not a perfect distribution of information – nor will there ever be.

Now, taking things to the next level, we ought to ask, “What is information?”. Because when one makes a decision, they are not only making a rational decision, but also acting from countless hidden, unconscious impulses. The advertising industry is predicated on this fundamental truth about human nature. Businesses hire advertisers not only to selectively provide specific information to consumers, but to actively craft messages that exploit the human unconscious. The fact that Tylenol exists is a testament to this fact: despite the generic being the exact same product, and sitting right beside Tylenol in the pharmacy aisle, Tylenol is a very profitable brand.

So the libertarian not only must deal with citizens not having access to equal levels of literal information, but unconscious and emotional information as well. The two together are what social scientists refer to as “human capital”.

Both of these together conspire to create a world in which the libertarian assumption of liberty through information really amounts to a world in which liberty is very unequally distributed. The coherent intellectual and moral response to this is to try and structure society in a way that maximizes information. Intellectually dishonest libertarians will peddle the claim that this social structure is one in which government is highly limited and markets are thus free.

But the obvious answer is that not only will information become even more stratified, but so too will the means of action. Wealth and information are power. Those who have more will always have an advantage. As we have seen throughout history, if left unchecked power will accrete. Liberty is eroded. The non-libertarian’s response is thus to strategically erect governmental bulwarks against this natural process.

Of course, the opposite of the libertarian, the communist, will end up doing much the same thing. Although instead of power accumulating among business oligarchs it accumulates in the state. Interestingly, both ideologies claim to be on “the side of liberty”. Yet if liberty is both information and the ability – conscious or otherwise – to act on information, neither system provides it. In fact, both actively destroy it. The answer then, which most responsible democracies have adopted, is a mixture of both market freedom and government regulation. The question is not whether regulation or markets are bad, but how you do them.

Conservative Institutions and Race

There's a lot of talk about racism and conservatism these days - whether it's the hateful signs at tea party rallies or calls for harsh immigration policy.

Conservatives are always a bit testy when liberals point out the high degree of correlation between their views and those of racists. This is understandable. The response is generally to A)deny that they are racist, B)point out that liberals can be racist too, or C)accuse liberals of playing the race card, i.e. trumping up charges of racism to score political points.

But what you never hear is any serious discussion of the original claim: why is there a high degree of correlation between their views and those of racists? It isn’t something that can be denied. Overt racist groups always have conservative views. “Lone wolf” racists, like those showing up at tea parties, wouldn’t dare go to a liberal rally. And anecdotally speaking, we all know people personally who have expressed racist views and they are generally conservative politically.

So assuming this is true, conservatives should respond with an intelligent examination of why this is so. Alas, instead we get an endless defensiveness and victimhood. It is as if conservatives genuinely don’t care about racism. From an academic and journalistic standpoint, this is certainly clear: very few conservative journalists or academics have sought to understand it objectively. In fact, attempts to explore the issue of race in America and elsewhere are generally considered part of a “liberal bias”. This is the deepest form of epistemic closure, where not only are certain views not to be discussed, but entire sections of reality.

So the question then becomes, why would an ideological framework as large as conservatism be so opposed to dealing with something so important as racism? Some of it is certainly defensiveness. But this doesn’t account for the failure of institutional conservatives racism on in a serious way on their own terms.

In an individual, psychologists would call this denial – a defense mechanism that denies painful thoughts. Obviously, most conservatives oppose racism. But why would racism be any more uncomfortable to a conservative than to a liberal? There must be something intrinsic to conservatism that actively discourages its exploration.

Conservatives are always a bit testy when liberals point out the high degree of correlation between their views and those of racists. This is understandable. The response is generally to A)deny that they are racist, B)point out that liberals can be racist too, or C)accuse liberals of playing the race card, i.e. trumping up charges of racism to score political points.

But what you never hear is any serious discussion of the original claim: why is there a high degree of correlation between their views and those of racists? It isn’t something that can be denied. Overt racist groups always have conservative views. “Lone wolf” racists, like those showing up at tea parties, wouldn’t dare go to a liberal rally. And anecdotally speaking, we all know people personally who have expressed racist views and they are generally conservative politically.

So assuming this is true, conservatives should respond with an intelligent examination of why this is so. Alas, instead we get an endless defensiveness and victimhood. It is as if conservatives genuinely don’t care about racism. From an academic and journalistic standpoint, this is certainly clear: very few conservative journalists or academics have sought to understand it objectively. In fact, attempts to explore the issue of race in America and elsewhere are generally considered part of a “liberal bias”. This is the deepest form of epistemic closure, where not only are certain views not to be discussed, but entire sections of reality.

So the question then becomes, why would an ideological framework as large as conservatism be so opposed to dealing with something so important as racism? Some of it is certainly defensiveness. But this doesn’t account for the failure of institutional conservatives racism on in a serious way on their own terms.

In an individual, psychologists would call this denial – a defense mechanism that denies painful thoughts. Obviously, most conservatives oppose racism. But why would racism be any more uncomfortable to a conservative than to a liberal? There must be something intrinsic to conservatism that actively discourages its exploration.

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

Manifest Arizona

With the recent controversy over Arizona's harsh new immigration law which gives the police authority to demand citizenship papers from anyone deemed "suspicious", one might be forgiven for asking why more conservatives, always such reliable defenders of "liberty" and "freedom", aren't up in arms. (And yes, I suppose that could be taken literally). The obvious answer is that it is directed at people who have clearly broken the law.

But the main problem with the bill is not that it is focused on criminal behavior, but that it is so ripe for abuse. It is granting authority to police officers that would simply not be tolerated if the either the intended target, or innocent citizens whose rights are now in jeopardy, were not Hispanic. This is of course, one of those "what if" situations endemic to racial politics that relies too much on supposition and not enough on evidence. But because we are not yet (yet!) in possession of mind-reading devices that would enable us to sniff out the bigots, I'll have to rely on some good old-fashioned theorizing

The glue that holds the conservative together is a profound sense of ethnic superiority - that who he is and what he does is right, no matter what. So the constitution, liberty and patriotism are wonderful to the extent that they are for him. Yet they are forever imperiled by those who are not like him. Not because those individuals are at all in conflict with the constitution, liberty, or patriotism, but because they represent an extension of those themes and rights that threaten his exclusive access to them. Women, immigrants, gays, blacks, atheists, Muslims, etc. - the great unassimilated masses - seek shelter behind rights he feels are somehow exclusively his.

It has been suggested that the Moses story has always been powerful in the American psyche. Apparently early colonists read it as they crossed the Atlantic. Westward expansion was a continuation of this search for the promised land - "promised" being the key word. Conservatism seems a logical extension of this historical narrative. While liberalism can be considered part and parcel of the same dynamic, a significant difference is the the emphasis of progressives and conservative traditionalists.

Progressives see the promised land not so much as an actual state of nature, but more a process of self-realization. The idea is less that there exists some state in which one perfect order is established, but that there be underlying critical structures that allow for a diversity of opinion and expression, and perfection will reveal itself along the way. Where conservatism is absolute and authoritative, progressivism is relative and democratic.

When the two political sensibilities are employed with mild dogmatism, they provide important checks upon one another. But when hewed to too vigorously, they become incoherent. To the progressive, there is no right and nihilism reins. To the conservative, there is only one right and all others must be beaten into submission.

But the main problem with the bill is not that it is focused on criminal behavior, but that it is so ripe for abuse. It is granting authority to police officers that would simply not be tolerated if the either the intended target, or innocent citizens whose rights are now in jeopardy, were not Hispanic. This is of course, one of those "what if" situations endemic to racial politics that relies too much on supposition and not enough on evidence. But because we are not yet (yet!) in possession of mind-reading devices that would enable us to sniff out the bigots, I'll have to rely on some good old-fashioned theorizing

The glue that holds the conservative together is a profound sense of ethnic superiority - that who he is and what he does is right, no matter what. So the constitution, liberty and patriotism are wonderful to the extent that they are for him. Yet they are forever imperiled by those who are not like him. Not because those individuals are at all in conflict with the constitution, liberty, or patriotism, but because they represent an extension of those themes and rights that threaten his exclusive access to them. Women, immigrants, gays, blacks, atheists, Muslims, etc. - the great unassimilated masses - seek shelter behind rights he feels are somehow exclusively his.

It has been suggested that the Moses story has always been powerful in the American psyche. Apparently early colonists read it as they crossed the Atlantic. Westward expansion was a continuation of this search for the promised land - "promised" being the key word. Conservatism seems a logical extension of this historical narrative. While liberalism can be considered part and parcel of the same dynamic, a significant difference is the the emphasis of progressives and conservative traditionalists.

Progressives see the promised land not so much as an actual state of nature, but more a process of self-realization. The idea is less that there exists some state in which one perfect order is established, but that there be underlying critical structures that allow for a diversity of opinion and expression, and perfection will reveal itself along the way. Where conservatism is absolute and authoritative, progressivism is relative and democratic.

When the two political sensibilities are employed with mild dogmatism, they provide important checks upon one another. But when hewed to too vigorously, they become incoherent. To the progressive, there is no right and nihilism reins. To the conservative, there is only one right and all others must be beaten into submission.

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

A Conservative Vision for California

In case anyone might be wondering what strange fuel was in fact burning within the engines of intransigence and dysfunction in the California assembly, Brad De Long points us to Victor Davis Hanson's recipe for a West Coast Conservatopia:

But packaged in vaguely populist and naive rhetoric, the message is much more digestible. This is what real conservatism looks like - in all its ugly ethnocentric nativism, environmental callousness, authoritarianism and disregard for the disadvantaged. There is certainly logic and principle beneath. But in an odd way, at this sort of mid-rhetorical level - where policy is clearly stated, yet the underlying philosophy hasn't yet been broken open to reveal its incoherence, the modern conservative mind is at its most raw and frighteningly radical.

All of which raises the question: how would we return to sanity in California, a state as naturally beautiful and endowed and developed by our ancestors as it has been sucked dry by our parasitic generation? The medicine would be harder than the malady, and I just cannot see it happening, as much as I love the state, admire many of its citizens, and see glimmers of hope in the most unlikely places every day.I will say this for the man: at least he has the balls to openly advocate what most conservatives can merely allude to. Of course, it's one think for a Standford professor to propose such things. It's quite another for anyone concerned with getting more than 10-20% of the public to go along with most of it.

After all, in no particular order, we would have to close the borders; adopt English immersion in our schools; give up on the salad bowl and return to the melting pot; assimilate, intermarry, and integrate legal immigrants; curb entitlements and use the money to fix infrastructure like roads, bridges, airports, trains, etc.; build 4-5 new damns to store water in wet years; update the canal system; return to old policies barring public employee unions; redo pension contracts; cut about 50,000 from the public employee roles; lower income taxes from 10% to 5% to attract businesses back; cut sales taxes to 7%; curb regulations to allow firms to stay; override court orders now curbing cost-saving options in our prisons by systematic legislation; start creating material wealth from our forests; tap more oil, timber, natural gas, and minerals that we have in abundance; deliver water to the farmland we have; build 3-4 nuclear power plants on the coast; adopt a traditional curriculum in our schools; insist on merit pay for teachers; abolish tenure; encourage not oppose more charter schools, vouchers, and home schooling; give tax breaks to private trade and business schools; reinstitute admission requirements and selectivity at the state university system; take unregistered cars off the road; make UC professors teach a class or two more each year; abolish all racial quotas and preferences in reality rather than in name; build a new all weather east-west state freeway over the Sierra; and on and on.

In other words, we would have to seance someone born around 1900 and just ask them to float back for a day, walk around, and give us some advice.

But packaged in vaguely populist and naive rhetoric, the message is much more digestible. This is what real conservatism looks like - in all its ugly ethnocentric nativism, environmental callousness, authoritarianism and disregard for the disadvantaged. There is certainly logic and principle beneath. But in an odd way, at this sort of mid-rhetorical level - where policy is clearly stated, yet the underlying philosophy hasn't yet been broken open to reveal its incoherence, the modern conservative mind is at its most raw and frighteningly radical.

But What Are Good Schools Actually Doing?

The NY Times profiles a Brooklyn public school that "succeeds despite the odds." While refreshing in that it isn't yet another glorification of a miracle charter school, I don’t see much going on in this article that doesn’t happen in most schools. It isn’t that there aren’t actual differences – just that the article didn’t really capture anything meaningful.

It did, however, point out that there is a waiting list for the school. While a sign that the school is indeed doing a good job, this leads to a selection bias (important because it skews population-based comparisons).

In his book, Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons From Chicago, Anthony Bryk analyzes data from 15 years of successful schools and comes up with 5 key elements of success:

It did, however, point out that there is a waiting list for the school. While a sign that the school is indeed doing a good job, this leads to a selection bias (important because it skews population-based comparisons).

In his book, Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons From Chicago, Anthony Bryk analyzes data from 15 years of successful schools and comes up with 5 key elements of success:

• Strong leadership, in the sense that principals are “strategic, focused on instruction, and inclusive of others in their work”;

• A welcoming attitude toward parents, and formation of connections with the community;Notice that testing is conspicuously absent. The reason for this is obvious to any teacher: assessment is standard good practice. Every good teacher does it, and they do it in a variety of ways that are 100x more meaningful than standardized testing. Standardized testing gives you relatively good data from the school or district level. But at the classroom level, its worthless for everyday instruction. As a part of a punitive process, it’s problematic for a number of reasons. A good principle with proper resources will find much more meaningful information from simple classroom visits and discussion with the teacher.

• Development of professional capacity, which refers to the quality of the teaching staff, teachers’ belief that schools can change, and participation in good professional development and collaborative work;

• A learning climate that is safe, welcoming, stimulating, and nurturing to all students; and

• Strong instructional guidance and materials.

Saturday, April 24, 2010

Social Retribution and Justice

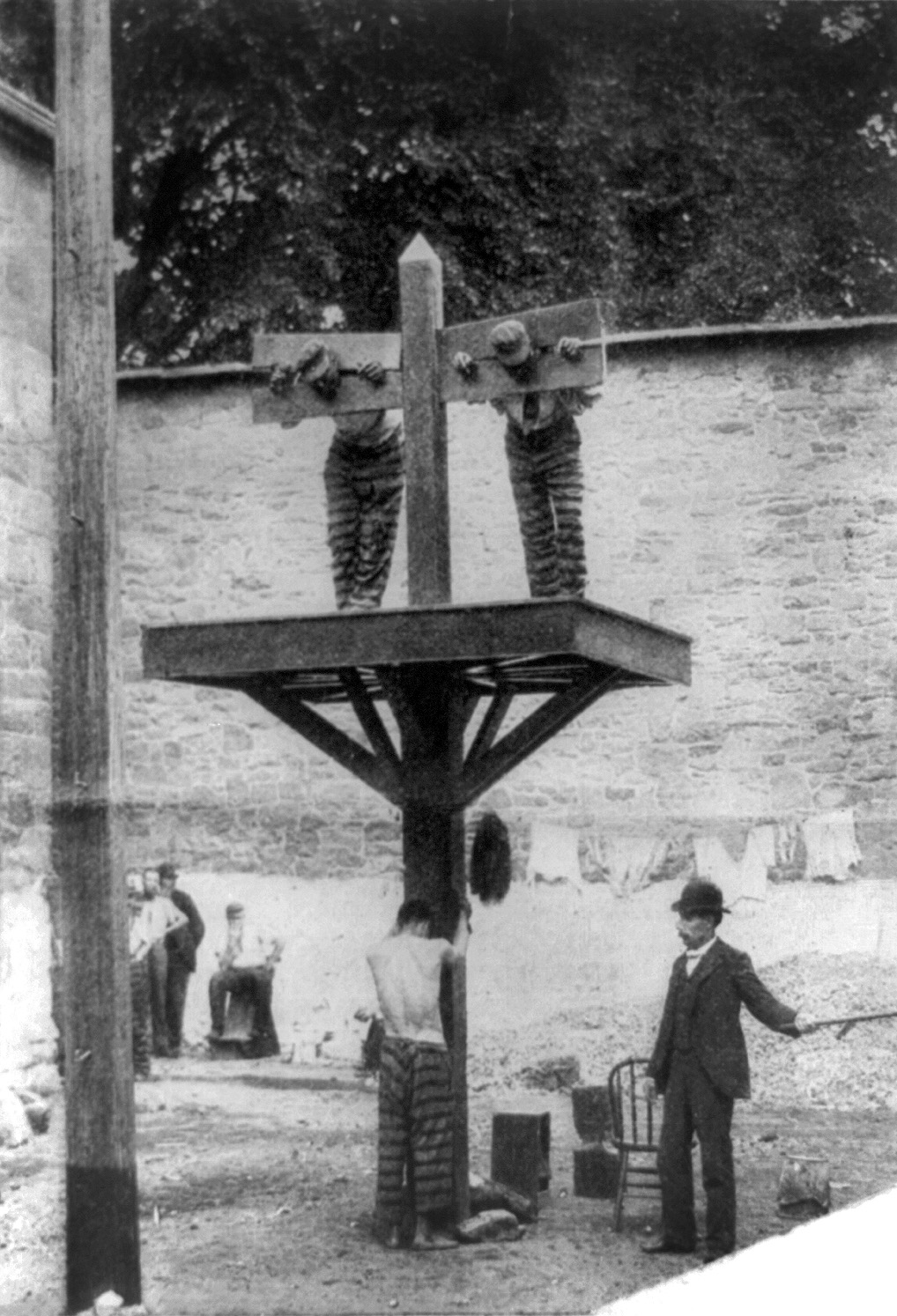

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/be/Prisoners_whipped.jpgIn discussing criminal justice philosophy, it was brought to my attention that I had been ignorant of the larger debate surrounding retributive justice. In further reading, I was stopped dead in my tracks. I'm now having a very difficult time wrapping my head around the arguments for retribution. Although they're seeming unavoidable.

Noah Millman sums up the argument for retribution, which he refers to as "satisfaction" thus:

So, how do you get the punishment to fit the crime, without resorting to the concept of social retribution and "just desert" - ideas I still find very squishy and problematic? What is interesting is one can see how appealing they are to the right, for a number of reasons.

The first is the emphasis on traditional social order. The individual act is not just seen as having consequences between victim and actor, but for the larger social order, which is defined by the codified response. Ironically, this seems the base argument for hate-crime laws, which tend to be frowned on by the right, yet exists to emphasize the special perniciousness of the crimes on the social order.

The second is, as Hector referenced, the emphasis on free agency. Conservatism is built on the acceptance of contra causal free will. If one believes that man has free agency, then it is much easier to embrace the idea of retributive justice. While the two are not dependent on each other, they do support one another. What contra causal free will is basically saying is that one knows both all of their impulses to act and then all of the consequences of their actions. Obviously this is absurd, and the argument will be that not all impulses and consequences must be known. But what then to make of the fact that everyone has different levels of this type of knowledge - which one can broadly call "consciousness"? And since the degree to which one is conscious of their impulses and consequences is determined by their environment and biology, we end up with an argument for determinism.

Retributive justice is much easier to embrace if one feels the actor had full awareness of the context in which the crime was committed: both their impulse and consequences. Thus if one "knew full well" that they should not have acted, yet did so anyway - violating the social order, then any demand for retribution is really justified. I think this is where you find so many on the right edging closer to the totalitarian concept of harsh sentencing. California's "three strikes" law is predicated upon this impulse: if you knew it was wrong you shouldn't have done it, thus you accept whatever punishment, no matter how harsh. The obvious problem with this is that it overlooks the fact that certain populations tend to be overrepresented in the criminal population, pointing to a social imbalance in impulse/consequence consciousness. Basically the determinist argument.

Yet I'm still stuck with the concept of social retribution in the first place. What does it mean to "repay one's debt to society"? Certainly, if someone stole my car, I would want to see them punished. But why? People ought to be deterred - if laws were not punished there would obviously be more criminal behavior. And society ought to be protected. But what to make of my desire for "justice"? I'm very skeptical of my own emotions. I would prefer there to be some more objective reality upon which to base social policy.

I wonder, however, if there isn't an easier solution: what if punishment is based on a reasonable level of deterrence? While I understand this would be difficult to determine, it doesn't seem much more so than determining punishment based on the squishy notion of social debt. My guess is that punishments would line up pretty well. A minor offense might be deterred by a minor punishment, while a major offense would require something more severe.

Of course, the failing here would be in determining "reasonable deterrence". Some people are simply not going to be deterred. Yet there is just as much flaw in the concept of social debt. How is it that certain demographics end up owing so much more social debt - especially considering that the worse life circumstances are, the more likely one is to offend. In that sense, society should forgive the offense, considering them even! The harshest punishment should go to those who have benefited most from society, and thus owe the most.

Noah Millman sums up the argument for retribution, which he refers to as "satisfaction" thus:

Satifaction. A crime is a harm – to the individual victim, but also to society, and arguably to God – that must be retributed. Fit punishment means exacting a consequence upon the malefactor proportionate to the offense, satisfying the offended that they are “even.” This is usually not presented as a consequentialist argument, but there is an implict consequentialism in any version that does not invoke the deity, in that the reason why the offended party must be satisfied (in general, even if not in every individual case) by public justice is that otherwise confidence in public order will be undermined, and recourse will be made increasingly to private justice, or vendetta. (Versions of the argument that invoke the deity may also be consequentialist if your theology takes at face value the many biblical assertions that offense to God risks His wrathful response.)While it was easy for me to see how punishment for a violent crime would involve emotion and thus retribution, what then about crimes, such as auto theft, where the emotional impulse isn't as strong, yet damage is clearly done? If justice is solely based on social protection, deterrence, and rehabilitation, how do you determine rehabilitation? You could easily see a murderer rehabilitated in less time than a mere thief.

So, how do you get the punishment to fit the crime, without resorting to the concept of social retribution and "just desert" - ideas I still find very squishy and problematic? What is interesting is one can see how appealing they are to the right, for a number of reasons.

The first is the emphasis on traditional social order. The individual act is not just seen as having consequences between victim and actor, but for the larger social order, which is defined by the codified response. Ironically, this seems the base argument for hate-crime laws, which tend to be frowned on by the right, yet exists to emphasize the special perniciousness of the crimes on the social order.

The second is, as Hector referenced, the emphasis on free agency. Conservatism is built on the acceptance of contra causal free will. If one believes that man has free agency, then it is much easier to embrace the idea of retributive justice. While the two are not dependent on each other, they do support one another. What contra causal free will is basically saying is that one knows both all of their impulses to act and then all of the consequences of their actions. Obviously this is absurd, and the argument will be that not all impulses and consequences must be known. But what then to make of the fact that everyone has different levels of this type of knowledge - which one can broadly call "consciousness"? And since the degree to which one is conscious of their impulses and consequences is determined by their environment and biology, we end up with an argument for determinism.

Retributive justice is much easier to embrace if one feels the actor had full awareness of the context in which the crime was committed: both their impulse and consequences. Thus if one "knew full well" that they should not have acted, yet did so anyway - violating the social order, then any demand for retribution is really justified. I think this is where you find so many on the right edging closer to the totalitarian concept of harsh sentencing. California's "three strikes" law is predicated upon this impulse: if you knew it was wrong you shouldn't have done it, thus you accept whatever punishment, no matter how harsh. The obvious problem with this is that it overlooks the fact that certain populations tend to be overrepresented in the criminal population, pointing to a social imbalance in impulse/consequence consciousness. Basically the determinist argument.

Yet I'm still stuck with the concept of social retribution in the first place. What does it mean to "repay one's debt to society"? Certainly, if someone stole my car, I would want to see them punished. But why? People ought to be deterred - if laws were not punished there would obviously be more criminal behavior. And society ought to be protected. But what to make of my desire for "justice"? I'm very skeptical of my own emotions. I would prefer there to be some more objective reality upon which to base social policy.

I wonder, however, if there isn't an easier solution: what if punishment is based on a reasonable level of deterrence? While I understand this would be difficult to determine, it doesn't seem much more so than determining punishment based on the squishy notion of social debt. My guess is that punishments would line up pretty well. A minor offense might be deterred by a minor punishment, while a major offense would require something more severe.

Of course, the failing here would be in determining "reasonable deterrence". Some people are simply not going to be deterred. Yet there is just as much flaw in the concept of social debt. How is it that certain demographics end up owing so much more social debt - especially considering that the worse life circumstances are, the more likely one is to offend. In that sense, society should forgive the offense, considering them even! The harshest punishment should go to those who have benefited most from society, and thus owe the most.

Thursday, April 22, 2010

Who to Blame for Prison Rape?

via Matt Yglesias, Liliana Seguara writes about the frightening prevalence of rape in American prisons.

I guess the main rationale for allowing this to continue is that because we use prison as a deterrent, then rape (as well as all of the other violence that goes on) would be an extension of that pressure. Of course it is barbaric, and so its allowance must be tacit. But there is a widespread cultural willingness to indulge in our own fantasies of vengeance. To the degree that we allow it, we are its perpetrators.

How we treat our prisoners is a powerful illustration of the incoherent way we think about human consciousness. We think they could have made different decisions, and so we lock them up. Yet the fact that prisons exist, and include such horrific conditions, seems an argument that deterrence doesn’t work – at least not for those that end up in prison. It seems the only evidence for deterrence working is the people who it pressured into not doing the crime.

So we have this massive population for whom deterrence did not work, and yet they are then forced to endure the punishment that ostensibly deters others. How could we show so little empathy? One reason I think is our willingness to indulge in vengeance.

It seems there are 3 main reasons for prison: deterrence, social protection, and rehabilitation. A fourth, perhaps falling under the category of deterrence, is punishment, more specifically social vengeance. As an emotion, it is purely selfish. Although it hides behind a facade of “justice”, all it really does is bring pleasure to the accuser. To the extent that it acts as a deterrent, it may be externally justified to a degree.

However its impulse is not driven by social policy considerations, but by basic emotional satisfaction. No one says, “I hope Bernie Madoff gets his in prison in order to deter future financial malfeasance.” The emotion is understandable, in that it comes from a sense of very real unfairness. But as a delivery of “justice”, it is little more than a satiation of emotional blood lust. In this respect, it isn’t really different than any other emotional satisfaction, such as sex, hunger or entertainment. This is evident in the rich history of literal revenge fantasy in popular entertainment.

The tragedy is that the criminal population, already a statistically disadvantaged demographic before landing in prison, becomes part of an organ of popular self-pleasuring. While each criminal represents an individual case of unfairness, the larger social stratification seems at least an equal injustice. And considering the inefficacy of prisons as social reform, as judged not only by their continued existence in such large numbers but by terrible recidivism rates, our stubborn refusal to reform them is absurd.

It is probably impossible to know exactly how many prisoners are raped behind bars. “According to the best available research,” reports JDI, “20 percent of inmates in men’s prisons are sexually abused at some point during their incarceration. The rate for women’s facilities varies dramatically from one prison to another, with one in four inmates being victimized at the worst institutions.” With some 2.3 million people behind bars in the U.S., the implications are nothing short of a human rights and public health epidemic.

I guess the main rationale for allowing this to continue is that because we use prison as a deterrent, then rape (as well as all of the other violence that goes on) would be an extension of that pressure. Of course it is barbaric, and so its allowance must be tacit. But there is a widespread cultural willingness to indulge in our own fantasies of vengeance. To the degree that we allow it, we are its perpetrators.

How we treat our prisoners is a powerful illustration of the incoherent way we think about human consciousness. We think they could have made different decisions, and so we lock them up. Yet the fact that prisons exist, and include such horrific conditions, seems an argument that deterrence doesn’t work – at least not for those that end up in prison. It seems the only evidence for deterrence working is the people who it pressured into not doing the crime.

So we have this massive population for whom deterrence did not work, and yet they are then forced to endure the punishment that ostensibly deters others. How could we show so little empathy? One reason I think is our willingness to indulge in vengeance.

It seems there are 3 main reasons for prison: deterrence, social protection, and rehabilitation. A fourth, perhaps falling under the category of deterrence, is punishment, more specifically social vengeance. As an emotion, it is purely selfish. Although it hides behind a facade of “justice”, all it really does is bring pleasure to the accuser. To the extent that it acts as a deterrent, it may be externally justified to a degree.

However its impulse is not driven by social policy considerations, but by basic emotional satisfaction. No one says, “I hope Bernie Madoff gets his in prison in order to deter future financial malfeasance.” The emotion is understandable, in that it comes from a sense of very real unfairness. But as a delivery of “justice”, it is little more than a satiation of emotional blood lust. In this respect, it isn’t really different than any other emotional satisfaction, such as sex, hunger or entertainment. This is evident in the rich history of literal revenge fantasy in popular entertainment.

The tragedy is that the criminal population, already a statistically disadvantaged demographic before landing in prison, becomes part of an organ of popular self-pleasuring. While each criminal represents an individual case of unfairness, the larger social stratification seems at least an equal injustice. And considering the inefficacy of prisons as social reform, as judged not only by their continued existence in such large numbers but by terrible recidivism rates, our stubborn refusal to reform them is absurd.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Race and the Problem of Identity

Inside Higher Ed has a fascinating interview with Lee Baker, author of a new book Anthropology and the Politics of Culture. He describes how the disciplines of anthropology and sociology have differed in their treatment of American Indians and Blacks, as well as other immigrant minorities. He makes the point that this arose because of the very different treatment of these groups by larger society.

So Barack Obama can have dark skin, but be raised in white culture, and still be considered black. But a white kids raised in black culture will always be considered white. And yet Obama, because of his skin color, had/has been forced into an identity that has been chosen for him. And yet then in dealing with it, he actively sought out black ethnic forms that were meaningful to him.

Does this make him any more black? What does that even mean? I'm white, and I've certainly sought out black ethnic forms, but I'll never be identified, or self-identify as black. Is Obama's embrace of black forms any more "authentic" than mine? He certainly had more external forces pushing him in that direction. Or, I suppose, one could also say that he had less external forces not pushing him in that direction.

I think all of this goes to the fact that race is such an illusive term. It has meanings which are both true and untrue, depending on circumstance. As a cultural description, either at the individual or social level, the concept of "race" is ultimately a fascinating window into the understanding of what culture itself means. In many ways, culture is a utilitarian mythological device. We can simply lose ourselves into it. By following its rhythms and activities, we can feel safe in knowing that there is something constant and true that we can rely on. Much like a family member or friend, we are able to take it for granted that its narrative will always be there for us, unchanging, not unexpected or disorienting. In many ways it simply comes down to the best means to an end. Of course, it is self-perpetuating, and can be as limiting as it is comforting.

He goes on to mention how prominent anthropologist Francis Boas was instrumental in the evolution of our concept of race.

Before World War II, the consumption of a pacified and out-of-the-way Indian in Wild West shows, World’s Fairs, and museums can be juxtaposed with the consumption of a dangerous and in-the-way Negro in blackfaced minstrelsy, professionally promoted lynchings, and buffoon-saturated advertising. World’s Fair organizers routinely rejected requests to erect African American exhibits, and philanthropists flat-out rejected requests to erect a museum to showcase African and African American achievements. While many performers dressed up to play “authentic” renditions of somber Indians, others blackened up to play exaggerated renditions of knee-slapping Negroes, and there was no African American analog to the Campfire Girls and Indian Guides; middle-class white kids never went to camp to dress up to play Sambo.

Many scholars believed the races were organized in an evolutionary hierarchy that began with savagery and moved through barbarism and ended with Christian Civilization. Franz Boas used the scientific method to demonstrate that races were not organized in a hierarchy, and that cultures should be viewed and understood within their own historical contexts. The notion that the world has multiple cultures and different races that are neither better nor worse, neither advanced nor retarded, can be attributed to the scientific work that Boas began in the 1890s. Although this had a significant long-term impact in terms of challenging the ideas of racial inferiority that served as the basis for Jim Crow segregation, Boas’s research articulated a particular racial politics of culture that provided a compelling argument against racial uplift and cultural assimilation.Many people often express the view that race, as a term, is outdated.. While I agree that it is indeed a vague and largely non-descriptive term, it still has productive meaning - even if it at the same time has pernicious qualities. This is because as a term, race can be is used as a false definition - but then as a description of the experience of that false definition, based on specific historical context.

So Barack Obama can have dark skin, but be raised in white culture, and still be considered black. But a white kids raised in black culture will always be considered white. And yet Obama, because of his skin color, had/has been forced into an identity that has been chosen for him. And yet then in dealing with it, he actively sought out black ethnic forms that were meaningful to him.

Does this make him any more black? What does that even mean? I'm white, and I've certainly sought out black ethnic forms, but I'll never be identified, or self-identify as black. Is Obama's embrace of black forms any more "authentic" than mine? He certainly had more external forces pushing him in that direction. Or, I suppose, one could also say that he had less external forces not pushing him in that direction.

I think all of this goes to the fact that race is such an illusive term. It has meanings which are both true and untrue, depending on circumstance. As a cultural description, either at the individual or social level, the concept of "race" is ultimately a fascinating window into the understanding of what culture itself means. In many ways, culture is a utilitarian mythological device. We can simply lose ourselves into it. By following its rhythms and activities, we can feel safe in knowing that there is something constant and true that we can rely on. Much like a family member or friend, we are able to take it for granted that its narrative will always be there for us, unchanging, not unexpected or disorienting. In many ways it simply comes down to the best means to an end. Of course, it is self-perpetuating, and can be as limiting as it is comforting.

The Angry Boys

There's obviously a high level of comfort on the right with intellectual dishonesty: sloppy facts, a failure to truly attempt to understand the opposition's perspective, and a willingness to engage in cynical rhetoric and fallacy. I think it's fair to say that there is some truth in conservatism - or at least, the conservatism emphasis is often important (liberals can just as easily agree to limit government when appropriate).

But beyond that sort of impulse-to-restraint, there just isn't much to it. Everything else is built upon either distrust of facts or outright pseudoscience. The only difference is in degree of adherence to the Truth: government bad, markets good. One is often reminded of the schoolyard boy - even the bully - who isn't interested in communicating so much as engaging in a blind power struggle.

So while you can find some conservative individuals with a sensible temperament, who are inclined to take each fact as it comes and look at both sides, the vast majority of conservatives exist within an endless cycle of reactionary politics. Attacked on all sides by "liberalism" - which is often merely the truth, the goal is to keep the ball moving down field. The cause is not any end goal, but the ideological war itself. This is why so little conservative literature deals with much other than an attack of some or another liberal idea. They aren't in the business of idea creation, but idea defense.

This explains their tolerance for so much crazy. On an individual level, it is the outright lying of congressmen or pundits. On a larger scale it is entire movements such as creationism, climate skepticism, supply-side economics, or financial deregulation - all ideas which are fundamentally divorced from reality.

While liberals certainly have their own struggle with blind ideological adherence, the difference is that liberalism is at its core relativistic. Relativistic to facts , that is. The goal is simply a better world, whether this comes about through keeping tradition or throwing it out, through relying on markets or government intervention, through private property or redistribution. It is open to trying new things, and no one group or idea is necessarily better than another "just because".

The problem becomes what to do when the world ultimately becomes "better". What will we do then? Conservatives argue that we have reached that point, and that any more intrusion by the state is unjustified - either because it is unnecessary or because it will get in the way. Their inability to see how obviously false this claim is is itself damning evidence of their own denial. But should we one day reach some version of a promised land, because of liberalism's inherent relativism it should be compatible with a dialing down of state intervention in favor of the status quo.

We have already seen this to a large degree as the philosophy learned a valuable lesson in humility from the hubris of communism. Conservatism may one day reach a point where it to may become more flexible and adaptive - indeed many of its forebearers never sought any less. Unfortunately without witnessing the horror of its own extremity - as liberalism did, it may be stuck in an endless cycle of revanchist frustration. Even modest state interventions in the democratic socialist model, no matter how necessary will never be fully accepted.

But the question today is still what to do with people who are blinded by ideology. You can't reason with most of them. The best you can do is it to expose their lies in the hope that they don't suck any more gullible people into their ideological cult. I think, in the grand scheme of things, conservatism's success has been long in the making. For centuries it has been bubbling through American discourse, finding strength in historical events particular to our nation, which have contributed a tempermental distrust in government and a trust in markets and individualism. Yet in the face of a reality in which liberalism is a necessary component of the modern democratic state, conservatism is forever in a state of defense.

The real problem is that discourse rarely reaches these philosophical heights. Stuck in trench warfare, the conservative response in the face of epistemic setback is strategic retreat - only to advance again from a different point on the battlefield. The battle may be lost, but the larger war rages on. Ironically, while conservative's sense of persecution (amplified again in the historical protestant religious narrative - which explains social conservatism's particularly acute form of pathos) is justified, conservatives themselves are much more interested in attacking liberals then liberals are in attacking conservatives. Liberals tend to spend time finding new ways to address issues they care about. Conservatives, considering most issues already resolved, spend most of their time defending themselves from the perceived threat of liberalism. That may just be what we're stuck with for the foreseeable future.

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

The Elephant at the Tea Party

I'm going to take Jamelle's word for it over at postbourgie when he says that there's been a bit of an internet uproar over Charles Blow's recent piece in which he wrote of the racial make-up of a tea party he attended:

I understand why it may not be the most polite, or diplomatic thing to say, but the elephant in the room is this: in today's world, conservatism is an argument for racism. One can be a racist and not be conservative. And one can be a conservative, and not racist. But the two certainly seem to go together like cookies and milk.

The reason for this is really quite simple. The most basic principle of modern conservatism is that we all create our own success; each of us, no matter our lot in life, is perfectly able to grab those bootstraps and give 'em a good tug. The problem is, decades after the civil rights act, there is still a profound amount of racial inequality. And while some of it might be explained by racist managers or schoolteachers, the overwhelming fact is that minorities just aren't doing that well.

Now, liberals have an explanation for this. It's the old story (now with 1000x more scientific data!) about good old social determinism. "You are what society wants you to be." The whole thing can get pretty complicated, but the internal logic is damn airtight: Beginning at birth, via structural mechanisms, social capital is built that will lead one into a statistically predictable social outcome. That's a fancy way of saying, "Growing up in a posh Greenwitch home is a lot better for you than a project in Detroit." (The sad thing is that we know how to change all this but... well that's a whole 'nother post.) Anyway, racial inequality solved.

Poor conservatism. It still believes in fairy tales. Well, at least the one about contra-causal free will. Conservatism can't have racial inequality as long as it's not law. According to its charming view of human nature, we can all be CEOs and corporate bankers, astronauts and doctors! And if we aren't, well it's our own damn fault for not dreaming!

But then there's the racial thing. If all this were true, then we should, year in and year out, see a pretty random distribution of success. Since no structural inequalities exist to hold us down, the same number of kids from Greenwitch should be going to Ivy League schools as kids from Detroit. Since all of us has, at the moment we turn 18, access to the same level of social capital, then we shouldn't see the effects of parenting, culture, schools, income, education, neighborhood, etc.

But wait... maybe there's something else that might account for the persistence of these social indicators. Something impervious to environmental and social pressures. Something inside these individuals that makes them behave this way... I know, how about their race?!!!!!!!!

Of course, the racial explanation is incoherent for a variety of reasons, none of which are worth getting into. But suffice it to say that, to someone maybe on the fence, not that comfortable with the whole lovey-dovey, multicultural, "let's try and change the world" thing - conservatism provides a nifty explanation for this seeming conundrum. Not that anyone will ever admit to it. It's kind of a hush-hush thing. I'm not sure one better even admit it to oneself. But then again, conservatives don't really believe in the power of the unconscious either...

(image: Pauline Lazzarini)

Thursday night I saw a political minstrel show devised for the entertainment of those on the rim of obliviousness and for those engaged in the subterfuge of intolerance. I was not amused.

I understand why it may not be the most polite, or diplomatic thing to say, but the elephant in the room is this: in today's world, conservatism is an argument for racism. One can be a racist and not be conservative. And one can be a conservative, and not racist. But the two certainly seem to go together like cookies and milk.

The reason for this is really quite simple. The most basic principle of modern conservatism is that we all create our own success; each of us, no matter our lot in life, is perfectly able to grab those bootstraps and give 'em a good tug. The problem is, decades after the civil rights act, there is still a profound amount of racial inequality. And while some of it might be explained by racist managers or schoolteachers, the overwhelming fact is that minorities just aren't doing that well.

Now, liberals have an explanation for this. It's the old story (now with 1000x more scientific data!) about good old social determinism. "You are what society wants you to be." The whole thing can get pretty complicated, but the internal logic is damn airtight: Beginning at birth, via structural mechanisms, social capital is built that will lead one into a statistically predictable social outcome. That's a fancy way of saying, "Growing up in a posh Greenwitch home is a lot better for you than a project in Detroit." (The sad thing is that we know how to change all this but... well that's a whole 'nother post.) Anyway, racial inequality solved.

Poor conservatism. It still believes in fairy tales. Well, at least the one about contra-causal free will. Conservatism can't have racial inequality as long as it's not law. According to its charming view of human nature, we can all be CEOs and corporate bankers, astronauts and doctors! And if we aren't, well it's our own damn fault for not dreaming!

But then there's the racial thing. If all this were true, then we should, year in and year out, see a pretty random distribution of success. Since no structural inequalities exist to hold us down, the same number of kids from Greenwitch should be going to Ivy League schools as kids from Detroit. Since all of us has, at the moment we turn 18, access to the same level of social capital, then we shouldn't see the effects of parenting, culture, schools, income, education, neighborhood, etc.

But wait... maybe there's something else that might account for the persistence of these social indicators. Something impervious to environmental and social pressures. Something inside these individuals that makes them behave this way... I know, how about their race?!!!!!!!!

Of course, the racial explanation is incoherent for a variety of reasons, none of which are worth getting into. But suffice it to say that, to someone maybe on the fence, not that comfortable with the whole lovey-dovey, multicultural, "let's try and change the world" thing - conservatism provides a nifty explanation for this seeming conundrum. Not that anyone will ever admit to it. It's kind of a hush-hush thing. I'm not sure one better even admit it to oneself. But then again, conservatives don't really believe in the power of the unconscious either...

(image: Pauline Lazzarini)

Cultural Expression, Oppression, and Transcendance

Will Willkinson talks to Andrew Potter about his book, The Authenticity Hoax on Bloggingheads. The discussion is fascinating, until Potter wanders into some really stupid commentary on race. Potter, in trying to parse what "black authenticity" might be - a very valid discussion - makes the nebulous claim that

Both Wilkinson and Potter are clearly out of their depth here - as am I. Race is a difficult subject that requires a lot of heavy lifting. But I think it is exactly right that "black authenticity" isn't connected to the slave heritage. Actually, I should say *necessarily*, because the legacy of discrimination certainly is.

The main problem is that it defines black ethnicity down, which is actually a larger racist notion (let me be clear that I think racism is a part of all our consciousnesses, black and white). Potter literally says that you can "decode" the way black men walk and dress by assuming that "they are trying to signal one of three things: that they don't have a job, they've been to jail, or that they deal drugs".

Yet how is this different than the essence of "cool"? Certainly there are a disproportionate number of black men in prison, dealing drugs, etc. And this is part of a legacy of discrimination that has its roots in slavery. But black culture is so much more complex than this! "Blackness" is many things: it is a healthy organic culture, it is a dysfunctional culture from oppression, and it is an epic culture of transcendence.