A guest-blogger for Megan McArdle has an interesting piece on the necessity of parents of special-needs kids to lobby for adequate resources for their child's education - and how this ultimately becomes an issue of class, as wealthier parents can afford to successfully navigate the bureaucratic world of educational advocacy. As a libertarian, McArdle, and presumably her guest, are no boosters of public education in general, in her mind no doubt making a false comparison between bloated, uncompetitive government inefficiencies and nimble, a la carte private tutelage. But the criticism - that public schools are often not providing adequate resources for special needs students - is perfectly valid.

The guest describes a dynamic of education law that when a public school can't provide reasonably adequate services, the parent can lobby for what she calls a "shadow voucher", with which they can "purchase" the care elsewhere. The guest argues that "malfunctioning" school systems often make it difficult for families to receive these vouchers. The issue of class enters when you consider that this opportunity requires substantial financial - as well as human and societal - capital.

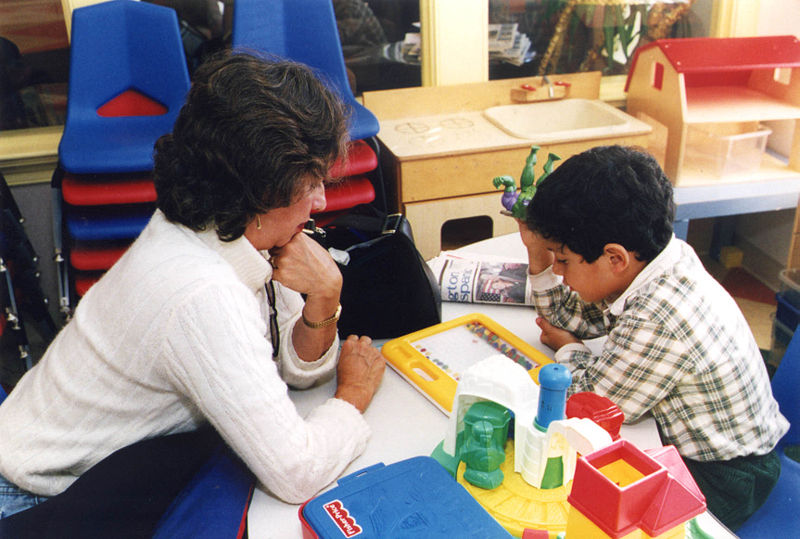

Where I become interested, is in the framing of adequate resources, and how its provision should be structured by the state. Traditionally, vouchers, and their effective modern incarnation, charters, have operated off the principle that ineffective provision of adequate resources fairly requires the ability of parents to receive publicly funded educational services elsewhere. Because of the rarity of special needs students, especially the specificity of many students' particular need, it is reasonable to ask whether a shadow voucher system makes sense. One does have to wonder however, how it is that private special-needs schools would be able to provide much better service at similar levels of funding. If the demand is there, why can't public schools provide similar levels of service? My suspicion is that providing a 1:1 teacher-student ratio is unheard of in public schools purely for financial reasons.In practice, as another manifestation of their failures, malfunctioning school systems will often fight with all the bureaucratic resources they can muster effectively against families who attempt to use the rights granted under IDEA to obtain services which differ from what the system is offering. Thus, families will often need to fight the malfunctioning school systems to obtain services for their special-needs children. Those fights are necessary even for wealthy families, as children with extreme needs require services which can outstrip even the ability of rich families to pay entirely out of pocket.My family has lived this reality for many years. We have a severely autistic son who has attended private schools which offer intensive behavioral therapy ("Applied Behavior Analysis" or "ABA," which is the only therapeutic methodology for which much evidence of effectiveness exists) with a student-teacher ratio of 1:1, and has also been receiving extensive ABA and other related services after school. Those schools and related services have enabled our son to make what progress he has been able to achieve. They are also necessarily and extremely expensive. But every single year, we have to "sue" NYC (technically it's not a lawsuit in a court but an impartial hearing as provided under IDEA, but it functions in very similar fashion) to cover the costs of such a school and services when they invariably recommend services far below what is necessary for our son to achieve any educational benefit.

In the case of general population students, where the needs are much less specific, there is no reason they cannot be served by traditional public school settings.

Proponents of vouchers/charters for general education argue that as a practical matter, students aren't receiving adequate education. However, their argument is that the issue is not resources, but teacher quality. Until such time as public schools are reformed, and adequate education is being provided, a family has the right to receive services elsewhere. Opponents argue however, that the problem is not teachers, but rather resources, specifically the lack of funding for resources to disadvantaged community schools. This places them in both philosophical and practical opposition, as the solution to teacher quality is not a matter of more funding, but bureaucratic structure - a problem appealing to free-marketeers and technocrats.

As I argue on this blog, the problem in education boils down to class, specifically that low-SES families have lower levels of financial, human, and societal capital, and therefore have a greater need for educational resources. The problem is not teaching, but SES, and a response from public institutions that provides adequate resources to meet disadvantaged populations. Making matters worse, high-capital families tend to raise enormous funds for their public schools, furthering the educational divide.

So, in our current situation, we face a similar problem with special needs students as disadvantaged students: access to resources. Even if we implemented a voucher system, it wouldn't cover the cost of more services, but rather a supplement for those able to afford the cost of extra services. In other words, a special carve-out for the affluent.

What is interesting about the case for shadow vouchers is the indictment not of teachers, but of the somewhat nebulously termed "malfunctioning school system". Obviously, special needs students - as the guest points out - have by definition special needs. This is clearly backed up by research. What is also backed up by research is the fact that low-SES students have special needs. Why, when we do not blame teachers for inadequate provision of services to special needs students, do we do so when we speak of disadvantaged students? What if, when faced with the proposition of teaching a class of developmentally delayed first-graders, we demanded more data and professional development, blamed "powerful unions"

and the quality of teacher programs, and insisted that calls for more resources was "making excuses"?

In a perfect world, every special needs child should receive adequate services, even 1:1 teacher-student ratios. But disadvantaged students should also receive adequate resources. They need aides. They need smaller classes. They need tutors, counselors, mentors, parent trainers, and social workers. Vouchers won't cover these costs, nor will equivalency funding to charter schools. Hopefully, we'll one day realize that, like special education, disadvantaged populations face - one would assume definitionally - disadvantages that require special educational resources.

No comments:

Post a Comment