As this is my first guest post here at Solutions for Schools, let me start by introducing myself. I currently teach science at a continuation high school, but I also have experience teaching kindergarten, as well as a number of years spent as a substitute in a number of districts around the country. Before I was a teacher, I worked in various areas of social services. I have a profound commitment to social justice and equality of opportunity for all citizens. I originally went into education because I felt that it was where I could do the most good in this regard. Unfortunately, the reality of what I have seen has disabused me of much of my former naivete. In community after community, I have seen a severity of developmental problems being dealt with heroically by local schools. Yet under-resourced and trapped in larger policy framework that fails to grasp the reality of the situation, they cannot help but fail in their mission of closing the achievement gap and guaranteeing every child an equal education.

Where I teach, the students are basically the "worst of the worst", in terms of academic, behavioral and emotional problems. Primarily juniors and seniors, their profiles are colored by severe truancy, substance abuse, mental illness (mainly depression), defiance and poor impulse control, broken homes, teen pregnancy and poor academic skills. They are incredibly diverse in life experience, with common denominators generally being poverty and low-parent income and education. At this point in their education, they are more in need of triage than anything else. Because they are credit deficient, and so fragile emotionally and behaviorally, they are given condensed curriculum packets that they can quickly finish and move on from. Even this however, proves too much for many of them too handle, and many disappear to never return, or spend days, weeks - even months - staring at their (admittedly) boring work and never completing any of it. Direct instruction is, as you might imagine, neither effective nor practical with this population. (As a non-tenured teacher, I was actually recently asked not to return by an administrator who insisted on direct instruction and was thus penalized when my students failed to be "properly engaged". There was likely an element of caprice involved as well, but suffice it to say that what I was doing was no different than any other teacher in the building, who all agreed that direct instruction was inappropriate, and whose students displayed equal levels of disengagement.)

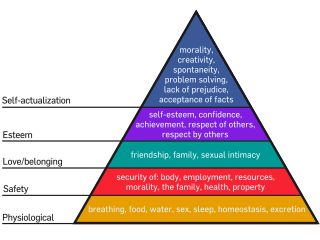

So, let us now look at why these students are so difficult to engage. Two ideas in education have powerful explanatory power here: Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs and Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development. The former essentially states that there is a hierarchy of human needs, and that lower levels must be satisfied before higher levels can be achieved. For instance, a lower level need like hunger will have a profoundly negative effect on higher order needs such as the acquisition of critical thinking or moral integrity. Vygotsky’s theory refers to “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, 1978). This concept is of central importance to foundational pedagogical ideas such as differentiation, scaffolding, and constructivism.

|

| Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Pyramid |

In my classroom, students exist in the lower levels of the needs hierarchy. Many of their affective behaviors can be seen as natural defense mechanisms, primarily the direct result of not having these needs met, and natural response mechanisms. Students are actually highly aware of this, routinely speaking of being stressed out. Unfortunately, their go-to responses tend to be highly dysfunctional: substance abuse, fighting, crime, or sex. That so much of the music they listen to is essentially a glorification of these unhealthy responses is indicative of a wider pattern throughout their communities. Many students, also, will speak openly of behaviors among family and friends - often adults - that are clearly unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Of course, these behaviors are considered unhealthy because of the detrimental effect they have both personally and in the community. It is therefore unsurprising that what goes on in the community will also go on in the classroom. With my students, this is literally true as fights break out with relative frequency, and students routinely come to school high or intoxicated. The janitor sometimes shows me the empty beer cans he retrieves from the bathroom. One student - a mother of a 2 year old - once came to my class late, reeking of alcohol. I let her in, and handed her the worksheet we were using with a video. During the lesson, she blurted out, "Mr. Rector, hurry up! I'm falling asleep!" Indeed, she passed out at her desk shortly thereafter.

Of course, I could have sent her to the office so that she could be suspended on suspicion. However this is something I rarely do, even when I have reason to suspect drug abuse is occurring. My reasoning is that there would be little point. Students are suspended right and left, and what this mainly means is that they get a short holiday from school. Remember, these students have records a mile long. The parents have long since lost control of them - and in many cases actively contribute to their dysfunction. No, I generally believe that my classroom is a "safe harbor". I would rather they be with me, safe, then anywhere else. I talk to them about their issues. I listen to their concerns and do my best to guide them to appropriate behavior. Punishing them often has the effect of building up their defensive walls, instead allowing them to come down so that healing can begin. Rebuilding trust is a critical step in the process of reintegration with positive social norms - as opposed to the negative norms of their peer group, or frequently that of their family. Evidence of the efficacy of this approach I believe has earned me the honor of one of the "best-loved" teachers in the school, and students routinely open up to me with their problems and concerns. What follows from this process of emotional growth is both an increased academic as well as behavioral classroom engagement.

This need for affirmation and rebuilding of trust is, I feel, the student's primary need. After speaking with the counselors, it became clear to me that if I wasn't going to do it, then no one would. The counselors had their hands full on procedural, academic matters, and never had the time to build the kind of student relationships required. A grant was once written for a psychological counselor, but therapy limited to one hour a week was impractical for a variety of reasons, the most salient being that rapport was still difficult to establish, and truancy was often an issue for the students in greatest need of help. As a teacher, I see the students one or two hours a day, and am able to build up enormous levels of trust and rapport. This can only happen in a non-direct instruction setting, when there is the time and environment conducive for casual discussion. A common technique of mine is to enter into a discussion between a group of students - non-schoolwork related, of course! - and through humor or genuine interest insinuate myself in the conversation. After a certain point in the year, the students actually actively welcome my insights. I tend to tell colorful stories, or try in some other way to creatively engage them so as to both respect their experiences and attitudes, but also to subtly guide them to more healthy modes of thought and behavior. In a way, it is a sort of psychological jujitsu - using their - often negative - thoughts and experiences to expose them to a more positive world.

I admit this is highly unconventional, and not something one could easily be trained in, or even really explain to someone who would not at least grasp it in some intuitive way. The technique doesn't always work, and my mistakes often haunt me. For instance, coming on too strong can risk a defensive reaction and dismissal as an outsider undeserving of trust. With such a fragile population, this can be disastrous. Many students will literally only come to school for the sake of one or another teacher who they feel a connection with. Breaking a fragile bond can literally mean the difference between dropping out and coming to school, or even something more serious, such as getting too high at a party or behaving too recklessly. I've seen too many students be pulled away from the brink by the love they receive from school staff to question its centrality to their lives. It also helps that I possess a relatively intimate knowledge of their culture. When students learn that I have my own rap album their jaws drop in disbelief! (Unfortunately, because of the explicit nature of some of the lyrics I only play them short snippets - which likely only increases the mystique).

So, how does any of this relate to academics? Do the students ever actually learn anything, or do they merely sit around and goof-off all day? Not if I have anything to say about it. Because of the instructional limitations I referred to previously, I have had to be very creative in developing from scratch a curriculum that is generalizable to a broad range of academic skill levels, is something that students will actually attempt to complete and not be put off by (a serious problem for many), is aligned with the standards, encourages higher-order thinking, and hopefully doesn't bore them to tears. At any given moment in a classroom, I will have students working in any area of any one of 4 quarters of either Biology or Earth Science. I spend my days facilitating their movement through the material, taking pre and post assessments, designing projects, and generally trying to keep them on-task, supplied with paper and pencils, etc. Many of them will still refuse to do much work. But it is my job to teach them, and every day I do my best to come up with ways of reaching them. Ultimately, even if they aren't going to leave my classroom knowing the difference between convection and radiation, or the process of protein synthesis, at least they will have experienced my love and support, and my unconditional belief in them. And in the end, this will no doubt help them more when dealing with the boss in a crappy service-wage position or - sad to say - pimp or prison guard.

Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal development tells us that learning is self-building, or, that new knowledge can only be integrated with the old. This is generally thought of in education in terms of academic development. A student with a reading level of 3 should not be reading a book at level 13. It would make much more sense to have them read a range of levels, say 1-6, the lower levels for confidence, the higher levels for skill building. As such, teachers must differentiate their instruction so as to target optimal levels of development and content integration. This is always a difficult task, and made more so in disadvantaged communities, where the developmental range in any one classroom can be vast.

But apart from academic skill, this model can be applied to different developmental domains. Students diverge widely in skill such as cognitive processing (something like the ability to organize ideas, or contrast new ideas with the old), or emotional regulation (taking time to breath before responding to an insult), or cultural and behavioral norms. We know from Hart andRisley that low-income children tend to come to school with vastly lower vocabularies. But an often overlooked aspect to their landmark study is the nuance in parenting styles accompanying that language gap, and the degree to which cognition is stimulated at home. For instance, in one home, a toddler who picks up an object and brings it to the mother might hear something like, "Be careful. Put that back. That isn't yours." While in another household, the child might hear something like, "What is that you have? Oh, it’s a stapler. Mommy uses that for papers. Yes, it's heavy. Let's put it back where it goes. Where is your ball?" These two responses represent not merely different parenting styles, but different levels of the kinds of environmental stimulus that build dynamic neural pathways. These compound for years and years, over thousands of hours, leading to widely divergent developmental skill-sets. Annette Lareau wrote powerfully of this in her book Unequal Childhoods.

Public schools in America have never been properly designed to handle such differing needs among a diverse public. For a number of larger socio-economic reasons, there exist profound developmental disparities across classes, and concentrated into different neighborhoods. The traditional model of one teacher and one classroom of 25-35 students drawn from the local community largely at random has been disastrous. Current attempts at reform have done little to address the underlying problem of development and differentiation. Excuses and exceptions have been found in an attempt to promote the notion that this model is sustainable. They have largely centered around the notion that individual teachers have simply not been doing a good enough job.

Yet this doesn't explain the overwhelming pattern of failure in poor schools, as the relative efficacy of teachers has been shown to be rather evenly distributed across affluent and poor schools alike. It is certainly the case that a less-effective teacher is going to do more harm at a poor school than she would at an affluent school. This would be true of any occupation. It is just as true that an effective teacher is going to be less effective at a school in which the student population is developmentally disadvantaged. Pretending that the solution is to find all the best teachers and send them to all the poor schools is not only highly unrealistic, but a bizarre way of looking at the problem. It would be as if our solution to a troubled war zone was not to invest in more resources or different tactics, but to blame ordinary troops and instead send in super-soldiers. I call this the "Rambo Escalante" model, based as it is on part fantasy, part misunderstanding of child development and the constraints of the current classroom model.

What then, would I propose in place of current reform models ultimately built around the notion that bad teaching is the problem, such as pay-for-performance, union busting charters, testing accountability and endless professional development? Critics have long assailed calls for more resources as "throwing money at the problem". Yet of course, this ignores the vast amounts of money NCLB has spent in pursuit of its goals. I'm not sure how much money my ideas might cost, but they will no doubt be expensive. If effective, however, they will pay for themselves many times over in increased productivity and reduced secondary social costs.

Some of what I think needs to happen is being implemented in small ways in different parts of the country, as individual programs are run in isolation. Yet it is rarely the case that a comprehensive system is established that truly intervenes in the developmental problem in a targeted, long-term way. The student I spoke of earlier, drunk in class with a two year old at home? What can be done for that two year old child right now, and for the next 16 years so that she will graduate with an equal chance of success in life, as a citizen with relatively equal prospects? Social services and educational institutions need to essentially close ranks, and envelop the child in a rich network of inter-connected, orchestrated outreach that assess and target her environmental needs so as to provide agile interventions both for her as well as her family. Her mother no doubt already has substance abuse issues. There are likely negative interactions with law enforcement among friends and family. The state is already no doubt intervening in their lives. I would propose however, the interventions - while conducive to the short-term safety of the rest of society - they are not conducive to the building of human and societal capital in that family cohort, and in many ways may be depleting it.

I don't know what a well-designed ecosystem of social services would look like. But I know what its functional purpose would be. And that, I fear, is more than can be said for too many of would-be education reformers today.

No comments:

Post a Comment