Political gaffes are interesting less because of what is said, but by how their interpretation on both sides of the aisle illustrates larger political themes. When Romney said "corporations are people too", he was likely talking about the shareholders and workers, who deserved to be included in the conversation. But this mattered less than the way it seemed to succinctly illustrate the left's perception of conservatives caring more about the profits of big business than their negative, corrupting effects in society.

Obama's recent gaffe about what small businesses - taken out of context to mean that small businesses are wholly reliant on government, likely in fact meaning that they are not wholly unreliant (two quite different claims) - illustrate what different political sides want to focus on.

In much of our political discourse, we have arguments over gut feelings, or

larger narratives with implicit assumptions, not by debating those grand

philosophical ideals, but rather by quibbling with details by proxy -

raising anecdotes, emphasizing facts that support our side, etc.

A bastard's take on human behavior, politics, religion, social justice, family, race, pain, free will, and trees

Friday, July 20, 2012

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

Towards An Optimistic Determinism

|

| The Gilded Cage, Morgan (1919) |

(For those unfamiliar with the debate: libertarian free will posits we are the original cause of our choices', and thus ultimately responsible; compatibilists and determinists acknowledge that we make choices, and feel as though we are free in doing so, we cannot actually "choose to choose" our choices, thus our will not originating within our consciousness.)

In a recent review of Sam Harris', Free Will, the reviewer - having largely ceded the determinist case - expresses an all-too common sentiment.

Couldn’t it be that we need the experience of what Wegner and others call “perceived control,” at least as a model of voluntary behavior, to get on with our lives and to have our achievements recognized and to be instructed by our failures? (Doesn’t Harris enjoy his success? I bet he does.) Finally, what happens to traditional qualities of character like courage, villainy, leadership? Poof! However correct Harris’s position may be — and I believe that his basic thesis must indeed be correct — it seems to me a sadder truth than he wants to realize.

So, why all the pessimism?

Rather than seeing determinism as a cold, subtractive, fatalism, I would argue the opposite – that current society is generally opposed to a determinist model, with some terrible policy implications. For starters, our criminal justice system is highly retributionist, terrorizing hundreds of thousands (with not only moral but practical implications – the almost complete lack of rehabilitative thinking). Understanding people as fully-caused would promote not only compassion, but an embrace of the science behind rehabilitation measures.

Income inequality is another. Too many currently feel that people are responsible, original causes of their successes or failures, leading to an acceptance of dire poverty and decadent wealth. Accepting determinism means acknowledging that biological and social privilege, combined with extant social structures are the original causes. This makes a moral case against inequality, as opposed to the notion of free will that apologizes for it.

At the very least, the notion of contra-causal free will overstates the case for reward and punishment. For while determinists much acknowledge the positive import of behavioral triggers like deterrence and success, they are in the end not only limited in their ability to drive behavior – only one factor among many others – but to the extent that they contribute to inequality, are immoral.

Finally, in terms of personal interactions and conscious development of self, determinism provides an enormous amount of grace and forgiveness. The more we are able to see one another as caused, the more we are able to accept each other as we are, not who we pretend to be, over-imagining agency where it does not exist. Often, the mere remembering of determinism is enough to occasion a soothing sigh and reminder to be compassionate and empathetic.

In the end, it seems much more liberating, if we must live caged, to do so fully aware of our humble position, rather than pretending to enjoy freedoms that do not exist.

Monday, July 16, 2012

God = Ego = Death, p.2

James Wimberly responds to my analogy of the ego as a dog in a rooftop crate on a car.

I see the point, and I'm not saying it isn't enormously useful. The angst alone has resulted in plenty of remarkable achievements. But as a part of a feedback loop, it's hard to think of anything as a driver - even self-awareness. With a lower animal, the stimulus is unreflective and external, and easy to think of as automatic. With humans, it's partly reflective, the stimulus being regurgitated through higher-order thinking processes such as compare/contrast, ordering, mathematics, prediction, etc. We facilitate in our young the development of highly complex identities that integrate all of these skills into an amazingly efficient and sophisticated platform for stimuli interaction. (You should see the way I interact with my children! I kid. I realize this all sounds absurdly cold. But it's only a framework for understanding.)

And yet, sophisticated as it is, there seems no reason to think of it as other than a feedback loop, operating according to laws of cause and effect, constrained by time itself, flowing from past to future. We learn from our past and the future is changed. Our agency in all of this seems entirely dependent upon past events, how our biological systems have integrated external stimuli. The idea of the ego as crate, as I have described it, is an attempt to get at this transcendent notion of the self not as superfluous, or useless - indeed it is the greatest thing ever created in the universe. But rather that it seems, as a thing *of* the universe, a mistake to assume that it is somehow a thing apart.

I'm reminded of the notion that, as creatures of a particular time, space and scale, we are biased to view the universe from a very particular perspective. We see a limited spectrum of light. We feel a particular gravity. We have a particular relationship with atomic particles. Yet, there exists a great range of electromagnetic waves we can't see directly. If we were 100th of our size, our weight would feel very different. If we could experience atoms at the atomic level, we would see a particles made up mostly of space. Our "common sense" experience would be completely different. An everyday example of this is how we still talk about the sun rising and falling, because it makes more *sense* to think of it that way. Relative only to us, it actually is rising and falling.

In this way, it seems we are trapped in a common sense view of consciousness in which we are the final agents of our agency. Yet clearly, we are highly developed beings that have spent years achieving this particular state of agency. And still, there are God knows how many forces (emergent or otherwise) at work on our every thought, pulling strings from deep within our psyche, like the dark matter of space, creating the context within which our thoughts enter our awareness. So how is it that our agency is not simply a manifestation of everything that has thus far come?

But now that we are here, in this final platform configuration, one might ask, are we not free then to go forward, to use all of this sophisticated mental equipment to do our bidding? My response would be: but from where does that "bidding" come? Again, we face the dark matter problem. Any bidding we would seem to choose has to arise from somewhere. And unlike galaxies that appear to have nothing around them, yet seem to exist in some miraculously ordered context, our bidding - our desire to choose - is surrounded not by nothing, but rather embedded deeply within an organic mechanism highly ordered and designed by the complex history of the individual, highly traceable and quantifiable - even to some extent predictable.

But not enough, right? This is the rub. The resolution on consciousness fantastically dim. In theory, by knowing every possible angle and trajectory of every particle one could determine the exact thoughts that might arise. But then you get into quantum problems and problems in constructing a model of emergence itself and it all seems so.. well, hopeless. But in the aggregate, people are incredibly predictable. Psychology, sociology and economics for instance tell us an enormous amount about human behavior. Animal behavior is even easier, right? When specific molecules attach to certain smell receptors, huge arrays of neuronal networks become very predictable. Just because we can't yet make the physical models for this process, can't we pretty safely assume there is a purely physical mechanism at work.

And much of this can be applied to humans. Place a bacon molecule in my nose and I will salivate. So far so mechanistic. Ditto for pornographic imagery. Violence. Food, sex, fear - all pretty simple, so to speak.

And then comes reflection. Consciousness. Higher-order thinking, memory, emotional regulation. While we can measure some of this stuff, the paths become infinitely more complex. Add to this the very real sense we have that we design our own thoughts. However, just because the sun comes up, it does not follow that the sun spins around the Earth. When I eat someone's sandwich from the lounge refrigerator and they get mad at me, I feel guilty. I feel like "I" did something wrong. "I" made a mistake. "I" am useful to myself as a thing, a thing to mold and correct, to improve upon going forward in the world. But whether a dog in a crate, or a spinning gyroscope, am "I" more than a device useful to the platform that is me, yet still utterly dependent on contextual forces that imprint memories? Neuroscience describes the way in which myelin sheaths around neurons serve to reinforce pathways of thought. Apparently they are underdeveloped when we are young, so as to facilitate creative thinking and the laying down of new avenues of thought. Yet as we age patterns become ingrained, and the sheaths thicken. Arterials become freeways. Rudimentary, but another piece of evidence towards a mechanistic understanding of conscious thought.

“Only along for the ride?” My image for this hypothesis is looking out of the rear window of the bus. The main objection to it is Darwinism. The brain we have is enormously expensive metabolically – and creates SFIK the most dangerous childbirth in nature. It would be contrary to everything we know about evolution to think that such consequential and high-priced developments as the self-aware, reflective brain come about for no adaptive reason.

I see the point, and I'm not saying it isn't enormously useful. The angst alone has resulted in plenty of remarkable achievements. But as a part of a feedback loop, it's hard to think of anything as a driver - even self-awareness. With a lower animal, the stimulus is unreflective and external, and easy to think of as automatic. With humans, it's partly reflective, the stimulus being regurgitated through higher-order thinking processes such as compare/contrast, ordering, mathematics, prediction, etc. We facilitate in our young the development of highly complex identities that integrate all of these skills into an amazingly efficient and sophisticated platform for stimuli interaction. (You should see the way I interact with my children! I kid. I realize this all sounds absurdly cold. But it's only a framework for understanding.)

And yet, sophisticated as it is, there seems no reason to think of it as other than a feedback loop, operating according to laws of cause and effect, constrained by time itself, flowing from past to future. We learn from our past and the future is changed. Our agency in all of this seems entirely dependent upon past events, how our biological systems have integrated external stimuli. The idea of the ego as crate, as I have described it, is an attempt to get at this transcendent notion of the self not as superfluous, or useless - indeed it is the greatest thing ever created in the universe. But rather that it seems, as a thing *of* the universe, a mistake to assume that it is somehow a thing apart.

I'm reminded of the notion that, as creatures of a particular time, space and scale, we are biased to view the universe from a very particular perspective. We see a limited spectrum of light. We feel a particular gravity. We have a particular relationship with atomic particles. Yet, there exists a great range of electromagnetic waves we can't see directly. If we were 100th of our size, our weight would feel very different. If we could experience atoms at the atomic level, we would see a particles made up mostly of space. Our "common sense" experience would be completely different. An everyday example of this is how we still talk about the sun rising and falling, because it makes more *sense* to think of it that way. Relative only to us, it actually is rising and falling.

In this way, it seems we are trapped in a common sense view of consciousness in which we are the final agents of our agency. Yet clearly, we are highly developed beings that have spent years achieving this particular state of agency. And still, there are God knows how many forces (emergent or otherwise) at work on our every thought, pulling strings from deep within our psyche, like the dark matter of space, creating the context within which our thoughts enter our awareness. So how is it that our agency is not simply a manifestation of everything that has thus far come?

But now that we are here, in this final platform configuration, one might ask, are we not free then to go forward, to use all of this sophisticated mental equipment to do our bidding? My response would be: but from where does that "bidding" come? Again, we face the dark matter problem. Any bidding we would seem to choose has to arise from somewhere. And unlike galaxies that appear to have nothing around them, yet seem to exist in some miraculously ordered context, our bidding - our desire to choose - is surrounded not by nothing, but rather embedded deeply within an organic mechanism highly ordered and designed by the complex history of the individual, highly traceable and quantifiable - even to some extent predictable.

But not enough, right? This is the rub. The resolution on consciousness fantastically dim. In theory, by knowing every possible angle and trajectory of every particle one could determine the exact thoughts that might arise. But then you get into quantum problems and problems in constructing a model of emergence itself and it all seems so.. well, hopeless. But in the aggregate, people are incredibly predictable. Psychology, sociology and economics for instance tell us an enormous amount about human behavior. Animal behavior is even easier, right? When specific molecules attach to certain smell receptors, huge arrays of neuronal networks become very predictable. Just because we can't yet make the physical models for this process, can't we pretty safely assume there is a purely physical mechanism at work.

And much of this can be applied to humans. Place a bacon molecule in my nose and I will salivate. So far so mechanistic. Ditto for pornographic imagery. Violence. Food, sex, fear - all pretty simple, so to speak.

And then comes reflection. Consciousness. Higher-order thinking, memory, emotional regulation. While we can measure some of this stuff, the paths become infinitely more complex. Add to this the very real sense we have that we design our own thoughts. However, just because the sun comes up, it does not follow that the sun spins around the Earth. When I eat someone's sandwich from the lounge refrigerator and they get mad at me, I feel guilty. I feel like "I" did something wrong. "I" made a mistake. "I" am useful to myself as a thing, a thing to mold and correct, to improve upon going forward in the world. But whether a dog in a crate, or a spinning gyroscope, am "I" more than a device useful to the platform that is me, yet still utterly dependent on contextual forces that imprint memories? Neuroscience describes the way in which myelin sheaths around neurons serve to reinforce pathways of thought. Apparently they are underdeveloped when we are young, so as to facilitate creative thinking and the laying down of new avenues of thought. Yet as we age patterns become ingrained, and the sheaths thicken. Arterials become freeways. Rudimentary, but another piece of evidence towards a mechanistic understanding of conscious thought.

Sunday, July 15, 2012

God = Ego = Death

James Wimberly questions the physical nature of consciousness.

I always return to Richard Hofstadter, who in his book, I Am A Strange Loop, came up with some fascinating metaphors for consciousness, based both on what we know as well as what we might infer (and a good deal of pure speculation).

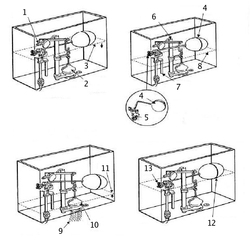

But he had a system he called the Hunecker scale, which measured consciousness, based on the principle that consciousness is ultimately about a series of feedback loops. One on the scale would be the simple mechanism of a toilet ballast which, sensitive to the amount of water filling up in the tank, receives feedback and stops the water flow. At the other end of the scale would be a sort of omnipotence, in which all future possible events are known. Humans would land somewhere in between, with lower forms of life occupying places further down the scale.

One of the things I like about this is that it seems to illustrate just this sort of gap between the material activity of the physical world and the elusiveness of consciousness. (Hofstadter spends considerable time in the book exploring different ways thinking about this problem.) I’ve always been struck by how ridiculously mechanistic people tend to be. Maybe it was the acid I took in my youth, but I’ve always felt we tend to anthropomorphize people too much.

So animal-like, we are mostly the only self-aware creatures on the planet. But this fact of supposed self-awareness seems only marginal to the larger complexity of our brain, the rest of which we have in common with most mammals, etc. I say “supposed” because in reality we aren’t very self-aware at all. Mostly we are incredibly un-self-aware, most of the time. And yet this tantalizing illusion that we are little Gods walking around thinking ourselves original, responsible and all the rest, this or that behavior somehow designed by us, that we are somehow in control of our lives, is such an – ironically – ego-feeding enterprise that we just can’t seem to quit it.

Yet as best as I can tell, this little ego-box in which we fly, strapped to fate no less than Mitt Romney’s crated Irish setter, is only along for the ride, pretending to run the show instead of merely enjoying it. Animals without much self-awareness surely experience all the same qualias. Yet what kind of consciousness do we assume in them? And as we travel down the brain-chain, what do we see but decreasing neural complexity? Hunecker after hunecker, myriad network dynamics shrink until we reach creatures that could hardly be described as thinking at all. Rather, they are mechanisms.

Apparently the enlightenment didn’t kill God, but merely made him human. An ironic reversal indeed. He ought to be finished off entirely.

Materialists say that it’s the matter that’s conscious, stupid, and laugh at the myth of “ghosts in the machine”. However that commits them to a strange view of matter. The physical properties of all instances of an elementary particle are identical. But some, a tiny proportion, support consciousness, by mechanisms not yet elucidated but, it is assumed, following the standard models of natural law. So all elementary particles (or possibly all particles of a particular common type; it may be the electrons or the protons) are consciousness-capable. If not, the materialist answer to the “what substance?” question is handwaving.

I always return to Richard Hofstadter, who in his book, I Am A Strange Loop, came up with some fascinating metaphors for consciousness, based both on what we know as well as what we might infer (and a good deal of pure speculation).

But he had a system he called the Hunecker scale, which measured consciousness, based on the principle that consciousness is ultimately about a series of feedback loops. One on the scale would be the simple mechanism of a toilet ballast which, sensitive to the amount of water filling up in the tank, receives feedback and stops the water flow. At the other end of the scale would be a sort of omnipotence, in which all future possible events are known. Humans would land somewhere in between, with lower forms of life occupying places further down the scale.

One of the things I like about this is that it seems to illustrate just this sort of gap between the material activity of the physical world and the elusiveness of consciousness. (Hofstadter spends considerable time in the book exploring different ways thinking about this problem.) I’ve always been struck by how ridiculously mechanistic people tend to be. Maybe it was the acid I took in my youth, but I’ve always felt we tend to anthropomorphize people too much.

So animal-like, we are mostly the only self-aware creatures on the planet. But this fact of supposed self-awareness seems only marginal to the larger complexity of our brain, the rest of which we have in common with most mammals, etc. I say “supposed” because in reality we aren’t very self-aware at all. Mostly we are incredibly un-self-aware, most of the time. And yet this tantalizing illusion that we are little Gods walking around thinking ourselves original, responsible and all the rest, this or that behavior somehow designed by us, that we are somehow in control of our lives, is such an – ironically – ego-feeding enterprise that we just can’t seem to quit it.

Yet as best as I can tell, this little ego-box in which we fly, strapped to fate no less than Mitt Romney’s crated Irish setter, is only along for the ride, pretending to run the show instead of merely enjoying it. Animals without much self-awareness surely experience all the same qualias. Yet what kind of consciousness do we assume in them? And as we travel down the brain-chain, what do we see but decreasing neural complexity? Hunecker after hunecker, myriad network dynamics shrink until we reach creatures that could hardly be described as thinking at all. Rather, they are mechanisms.

Apparently the enlightenment didn’t kill God, but merely made him human. An ironic reversal indeed. He ought to be finished off entirely.

The 'Values" Excuse

|

| Mohammed visits unfaithful women in Hell, 15th c. |

Less than 10 percent of the births to college-educated women occur outside marriage, while for women with high school degrees or less the figure is nearly 60 percent.It illustrates this divide by contrasting the lives of two families - one working class mother struggling to pay the bills for herself and three kids after the no-good father left, and two middle-class parents able to afford yearly cruises, good schools for the kids and extra-curricular activities. The stories are meant to paint a picture of what usually happens, not what is possible. Many single mothers are able to find jobs that support their families comfortably, and send their children to college. But this is not the norm. Statistically, they tend to be less educated, and their children ending up so.

What is so often missing from these stories is a sense of causality. We see a correlation between education and stable families. But what does that mean? Is it a simple matter of income? Surely, better pay means a mother is better able to afford a nicer neighborhood, with nicer schools and a safer environment. But this doesn't explain how it is that undereducated families are less stable, births are often out of wedlock, and from multiple partners.

It seems easy to make hand-waving claims about declining morality and values. If these people would just have safe sex, or wait until they find a good partner - demonstrating proper values, their children would have stable homes, and an opportunity for more success. Indeed, decades ago, this was clearly happening.

Yet, even in the "good old days", we still had poverty and economic segregation. It wasn't as if all that family stability was enforcing economic mobility. The lower classes were still staying poor. Poverty still meant poor neighborhoods, more crime, worse schools, etc. It's easy to look at staggering numbers about family breakdown and assume it is responsible for poverty today, considering that family instability is suboptimal.

But let us return to the question of why exactly it is that the poor seem to have more trouble forming lasting family bonds. Why are so many children being born out of wedlock, to parents unable to stay together, with fathers out of the picture.

In the story, details are not given but the father of the poor mother's children is implied to have been somewhat of a menace, finally requiring police to remove him from the house in the end. One can imagine that, decades ago, the scene might have played out differently, with the mother quietly suffering her partner's behavior. Indeed, they would no doubt have been married - the young woman resigned to her primary role in life as obedient wife. Would it be so terrible a thing if social norms evolved to allow for a woman to dream of more, even if it meant lower on average rates of family stability?

And yet, the poor will still be poor. This economic reality of capitalism cannot be denied.

A question I have is why affluent couples have higher rates of family stability. The gap is clearly enormous. And any social norms that evolved over the decades are lining up along class lines, not being distributed evenly. Is Charles Murray correct in assuming that the affluent have better values? What does that even mean? The affluent tend to do a lot of things that give their children advantages. They performed better in school, the went to college, they read more to their children. They also grew up in nicer neighborhoods, went to nicer schools - with "nicer" children, and generally inherited opportunities for social advancement that the poor did not.

All of this is the stuff of human and societal capital. It is not simply a "value". The term value implies a clear choice. But the choice is not clear, it arrives from the vast accumulation of life experiences one has. It isn't as easy as simply possessing the "value" of choosing to have protected sex, choosing a partner you know will be a good father, or choosing to work hard in school and finish college.

And yet it is enormously difficult to tease out what any individual's accumulation of experience ultimately has been, such that causality can be traced to the final problematic decision or outcome. Articles like these, can only ever - in the course of a few pages - not only set the table for sociological discussion, but dig very deeply into an individual's lifelong developmental trajectory. The forces at work are myriad and complex, interacting dynamically to push and pull an individual through time and space, society and consciousness.

In order to truly understand how class works, we must broaden our scope to include not merely one individual's conscious decision-making process, but the larger social structure in which they have developed, with a careful accounting of the advantages and disadvantages they have been afforded. Things like attitudes, values and behaviors are merely the products - the symptoms - of social privilege, and ultimately the product of capitalism's economic requirement for a permanent underclass. To see them as primary causes is not only lazy, but philosophically incoherent.

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

The Other 1%

Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in the NY Times today about his own troubled interaction with schooling, and his dream that his son not experience the same failures he did. Coates' parents grew up poor, but found consciousness and knowledge. His father, Paul Coates, eventually became a black panthe,r and through his devotion to the power of literature, founded the Black Classic Press, "one of the oldest independently owned Black publishers in operation in the United States."

In his memoir, Coates describes growing up on the mean streets of Baltimore, having to force himself to act tough when his real interest lay in sports and comic books. His father took pains to reinforce this defensive ability and enrolled him in a notoriously violent school. One might imagine his father was not only interested in imparting street smarts, but so too a conscious perspective of black struggle. This was the real black experience - poverty, ghettos, violent schools and thuggishness - all conspiring to deplete consciousness. Incarceration, low-wages, single-parenthood and broken homes were all a part of the reality of the underclass, a class black people had been propelled into over centuries of oppression, and only now was it finally becoming possible to see the light at the end of the tunnel. Clearly, the work was not done, and Coates' father knew his son had to be a part of the struggle.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is now a senior editor of the Atlantic. Although he struggled in school, and eventually dropped out of college, he picked himself up after landing a job writing for the Washington City Paper. His is the kind of boot-strap story that America loves to tell itself. Anything is possible. All it takes is hard work and determination. Anyone can be successful. If a poor kid from Baltimore can do it, so can anyone.

Yet the reality of these stories always belie their falsity. The truth is that Coates had advantages that most young men in his neighborhood did not. Not only did he have a bookish temperament that would later serve him well by the norms of larger society, he was raised by a father who, though not without flaws, obviously was incredibly smart and exposed his son to a world of intellectual aspiration that was exceedingly rare. Indeed, if every father in the ghetto had the consciousness of Paul Coates, there would be no ghettos.

It takes no great imagination to see how the privilege of the "1%" virtually ensures their legacy of wealth for future familial generations. Yet so too does the privilege of an intellectual 1%, imbuing as it does a consciousness that forms the basis of agency-building human capital. This is the stuff of societal capital, a concept I return to frequently on this blog. Paul Coates' represented great resources of societal capital that in turn allowed Ta-Nehisi to develop the human capital that would eventually parlay into future social success.

A fundamental flaw with boot-strap stories is that they assume the possibility of self-created agency - as if we somehow design our efforts to be successful. Coates did not, as a boy, decide to be a bookworm instead of a thug. It came naturally to him. It comes "naturally" to all of us. In fact, when it does not come naturally to us, it is due to some lesson of circumstance that forces upon us some new way of thinking or being. The term naturally itself seems defined by the idea of forces beyond our control, outside our powers of influence. Coates bookishness, combined with his father's guidance, put him far beyond his less-developed peers.

This cannot but lead to a vision of inequality as injustice, as our relative successes or failures cannot be separated from determining factors in our lives. This uncomfortable logic worries many into denying it post hoc. Yet when we examine human behavior, we see interactions between society and temperament that leave little room for determination that does not come from circumstance, in other words self-created self-agency.

In his memoir, Coates describes growing up on the mean streets of Baltimore, having to force himself to act tough when his real interest lay in sports and comic books. His father took pains to reinforce this defensive ability and enrolled him in a notoriously violent school. One might imagine his father was not only interested in imparting street smarts, but so too a conscious perspective of black struggle. This was the real black experience - poverty, ghettos, violent schools and thuggishness - all conspiring to deplete consciousness. Incarceration, low-wages, single-parenthood and broken homes were all a part of the reality of the underclass, a class black people had been propelled into over centuries of oppression, and only now was it finally becoming possible to see the light at the end of the tunnel. Clearly, the work was not done, and Coates' father knew his son had to be a part of the struggle.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is now a senior editor of the Atlantic. Although he struggled in school, and eventually dropped out of college, he picked himself up after landing a job writing for the Washington City Paper. His is the kind of boot-strap story that America loves to tell itself. Anything is possible. All it takes is hard work and determination. Anyone can be successful. If a poor kid from Baltimore can do it, so can anyone.

Yet the reality of these stories always belie their falsity. The truth is that Coates had advantages that most young men in his neighborhood did not. Not only did he have a bookish temperament that would later serve him well by the norms of larger society, he was raised by a father who, though not without flaws, obviously was incredibly smart and exposed his son to a world of intellectual aspiration that was exceedingly rare. Indeed, if every father in the ghetto had the consciousness of Paul Coates, there would be no ghettos.

It takes no great imagination to see how the privilege of the "1%" virtually ensures their legacy of wealth for future familial generations. Yet so too does the privilege of an intellectual 1%, imbuing as it does a consciousness that forms the basis of agency-building human capital. This is the stuff of societal capital, a concept I return to frequently on this blog. Paul Coates' represented great resources of societal capital that in turn allowed Ta-Nehisi to develop the human capital that would eventually parlay into future social success.

A fundamental flaw with boot-strap stories is that they assume the possibility of self-created agency - as if we somehow design our efforts to be successful. Coates did not, as a boy, decide to be a bookworm instead of a thug. It came naturally to him. It comes "naturally" to all of us. In fact, when it does not come naturally to us, it is due to some lesson of circumstance that forces upon us some new way of thinking or being. The term naturally itself seems defined by the idea of forces beyond our control, outside our powers of influence. Coates bookishness, combined with his father's guidance, put him far beyond his less-developed peers.

This cannot but lead to a vision of inequality as injustice, as our relative successes or failures cannot be separated from determining factors in our lives. This uncomfortable logic worries many into denying it post hoc. Yet when we examine human behavior, we see interactions between society and temperament that leave little room for determination that does not come from circumstance, in other words self-created self-agency.

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

See No Evil, Hear No Evil: The Case Against Unfair Taxation

|

| See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil, Philip Absolontion |

"3,000 people in the past two years may have had close contact with contagious people at Jacksonville’s homeless shelters, an outpatient mental health clinic and area jails.Conservative commentariate push-back on Kleiman's post argues that the hospital was a perfect example of unnecessary, wasteful spending. These people could easily have been treated at regular hospitals.

....

Treatment for TB can be an ordeal. A person with an uncomplicated, active case of TB must take a cocktail of three to four antibiotics — dozens of pills a day — for six months or more. The drugs can cause serious side effects — stomach and liver problems chief among them. But failure to stay on the drugs for the entire treatment period can and often does cause drug resistance.

At that point, a disease that can cost $500 to overcome grows exponentially more costly. The average cost to treat a drug-resistant strain is more than $275,000, requiring up to two years on medications. For this reason, the state pays for public health nurses to go to the home of a person with TB every day to observe them taking their medications.

However, the itinerant homeless, drug-addicted, mentally ill people at the core of the Jacksonville TB cluster are almost impossible to keep on their medications. Last year, Duval County sent 11 patients to A.G. Holley under court order. Last week, with A.G. Holley now closed, one was sent to Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami. The ones who will stay put in Jacksonville are being put up in motels, to make it easier for public health nurses to find them, Duval County health officials said."

The treatment of TB had indeed been making the hospital less necessary. However, lest we assume that the hospital was indeed inefficient, Wikipedia states that,

"With the discovery of drugs to treat tuberculosis patients outside of the hospital setting, the daily census at the hospital by 1971 dropped to less than half of the original 500. By 1976 the beds and staff at A. G. Holley were reduced to serve a maximum of 150 patients. As space became available, other agencies were invited to move onto the complex to utilize the unique environment."

It would be easier to believe that Republicans gave a shit if so much of their identity and political philosophy didn’t rest on principles that excuse them from giving a shit.

To recap:

1. The poor are poor because they lack initiative/common sense and thus choose poverty; people “choose” their lot in life.

2. Taking care of them creates moral hazard that promotes more poverty.

3. Government is less efficient/more corrupt than private markets, i.e. charity.

4. Charity should be left to non-profits and families, not the “nanny state”.

5. The wealthy have earned their wealth by themselves, and thus owe no greater percentage of taxes to anyone.

6. Taxes are often little better than theft, and thus progressive taxation is tantamount to fascism.

7. Redistributive policies are driven by envy and class warfare, not practicality, moral concern, or social responsibility/justice.

8. The problems of the poor aren’t nearly as bad as liberals make them seem.

9. The liberal media present these one-sided stories unfairly.

10. Back in the good old days people took care of themselves.

11. Social programs inevitably lead to serfdom and socialism.

12. Democrats only offer such programs to earn votes from the poor (who probably shouldn’t be voting anyway).

13. Liberals have actually created the social dysfunction we see today with all their hippie sex and feminism, so it’s their fault.

I’m sure I left out plenty. Of course not all Republicans would agree with every item (although Libertarians surely would). But you’d be hard-pressed to find one who didn’t agree with at least half.

If one truly believes these things, then why would one support the state helping the poor at all? To come out and say these things explicitly on a daily basis would surely expose one as heartless, cruel and well, lacking in common decency. And so these principles are only heard when conservatives are pressed. Instead, we hear about cutting taxes, balancing the budget, wasteful spending, limited government, and annoying liberals who whine about the poor, racial discrimination, worker rights, and any other cause that might remind one of the suffering and injustice that exists in society.

Hopefully, one presumes the conservative must feel, maybe if they just stop talking about it the "problems" will simply go away.

Monday, July 9, 2012

The Wealth Producers

|

| H. J. Heinz factory workers, 1909 |

According to Wikipedia,

Productivity is a measure of the efficiency of production. Productivity is a ratio of production output to what is required to produce it (inputs). The measure of productivity is defined as a total output per one unit of a total input.An assumption commonly made by those not progressively inclined is that labor compensation ought to follow productivity. In other words, pay ought to reflect one's productive contribution. This is a reasonable enough proposition. But what is often overlooked are the unseen factors involved in production. There is a tendency to view those who's productivity is associated with larger quantities of production as being more productive than they actually are. Thus, a manager of 100 employees is seen to be much more productive than a single employee, as he is responsible for the net production of one hundred people, rather than one person. His contribution is less the creation of goods, but rather the management of structures involved. To the extent that he creates efficiency, he is adding value. But it is a mistake to measure his value by the end product, as his role is much more limited.

Because productivity is a combination of what the worker brings to the table, as well as the structures at their disposal, man digging a ditch with a shovel is less productive than a man using a backhoe, even though his work is much harder. The man with the backhoe has the advantage of the structure which designed, developed, purchased, etc. the backhoe. What he brings to the table might be his skill with operating it, yet that depends on the structures that trained him. His increased productivity is thus a result of larger social systems.

This is the thinking underlying progressivism, that there are systems in place that facilitate and allocate different levels of production and capital (human/societal/financial). These systems tend to solidify inequality in very real ways, ways that create an unfair distribution of capital, which results in rewards not being just. All manner of factors conspire to limit freedom of individuals to access agency-increasing capital.

There is a moral case here for progressive redistribution. But there is also an economic argument, in that a degree of redistribution of capital lubricates individual agency and promotes innovation. For instance, libraries, public schools, health care, minimum wages, etc. all redistribute capital in ways which promote human agency by more evenly spreading it around society and allowing more creative enterprise to develop.

The last thing you want is capital stuck in the hands of the few, with fewer opportunities for it to be leveraged into growth. The meritocratic argument assumes that the high levels of inequality and wealth concentration we currently see are a function of those best able to allocate, manage and create growth. Yet this is a post-hoc justification of power structures that are often not a function of merit at all, but rather systemic privilege.

Sunday, July 8, 2012

Real Accountability

|

| Education, Gyula Derkovits 1923 |

"Here in the real world, no matter how brilliant your teachers are and how solid your curriculum is, you'll never get 100% of your kids to pass a standardized test."

What's kind of weird to me is what this statement reflects about A) our lack of knowledge about education and B) our misplaced priorities.

For me, the beauty of NCLB was always that it was about shining a giant spotlight on the achievement gap. The tragedy was that it had no idea how to go about remedying it, apart from a silly scheme for teacher accountability and school competition.

A decade later, Kevin's statement rings absolutely true. While everyone is mightily aware of the achievement gap, there has been almost no real progress, and everyone thinks that the problem is either crappy or poorly-trained teachers (protected by corrupt unions), or insurmountable social problems.

Yet as a teacher, the problem doesn't actually seem so hard. If I have 30 students - 10 of them at or above grade level, 10 maybe a year behind, and 10 more even further (a standard arrangement in low-SES classrooms), my job is to get them all to grade level by the end of the year.

Unfortunately, low-SES populations have serious disadvantages. The lowest performers will have serious behavioral problems, poor attendance, and severe lack of motivation. Parent support will be minimal, as many parents will not have the time or know-how to help their children be successful. As a teacher, I will only have so much time to give all 30 students the kind of individualized instruction and attention required for them to achieve peak performance. In a 55 minute lesson, after housekeeping, a brief lesson, even in the most well-structured classroom many students will fall through the cracks.

Compare this with a higher-SES classroom, where kids are generally better prepared, closer to grade level, have better attendance and support at home, fewer behavioral problems, the job will always be much easier.

So, aside from accountability and competition, what to do? What I have listed are usually dismissed as "excuses". Yet they are real problems that, when waved off as "excuses", the practical effect is that they are ignored. Thus, the very problems central to closing the achievement gap are being ignored. Is it no wonder that hundreds of thousands of teachers are frustrated beyond measure, and that morale is at an all-time low? Could you imagine soldiers in a losing battle complaining that there wasn't enough support - body armor, bullets, rations, troops, etc. - and their concerns being dismissed as "excuses"?

What if our priority was in fact to actually listen to teachers (and the research), and find ways to target specific issues, interventions designed to take the real cause of the achievement gap head-on? We aren't going to be able to solve larger issues of poverty, but we can look at what the specific effects on student achievement are, what specifically happens in the classroom because of them, and design our public education system accordingly.

To me, that is real reform and real accountability.

Wednesday, July 4, 2012

The Right Wing Crap Rocket

Jaime works hard. Everyday he wakes at the crack of dawn, pulls on his work boots and sets out for a long day of mowing lawns and digging ditches in the hot sun. His wife, Maria, wakes, gets the kids off to school, then dons her uniform, packs up her cleaning supplies and takes the bus to the wealthy houses on the hill where she will spend the day scouring toilets and polishing crystal. Together, they make less than $30K a year, yet do not have health insurance and employment can be fragile. They live in a modest home in a poor neighborhood, always seemingly on the edge of getting by.

By all measures, Jaime and Maria represent the lower end of inequality; their reward for their hard work is in no way equal to the rewards earned by the affluent. Yet, there a creepy argument on the right that this sort of inequality is actually good for society. It provides an incentive for people to strive and be more productive. The low pay and devaluing of certain jobs actually function as an inspiration to social mobility. No one wants to earn low pay for low-status work - especially work that is back breaking and mind-numbing. Therefore, these jobs act as behavioral reinforcers of productive economic activity, investments in one's skill-level and striving for a better life. How can one strive for what is "better" if there is no "better"?

This narrative is deeply embedded in our national political conversation. It is to some extent true. Those of us who are not low-skill, low-wage, low-status workers, we are glad we are not and no doubt at some point in our life made a conscious decision to not wind up as one. We like to tell ourselves that we are "deserving" of our higher wages and status because of our merit, the skill we have acquired that allows us to offer more than arms to dig or clean with. In many ways, there is a strong correlation between pay and merit, in the sense that the more one has to offer, the more one is compensated for it. As an educator and parent, forefront in my mind has been the future career prospects of my students and children. A hallmark rallying cry of public education in the past decade has been that "every child have the opportunity to go to college". A worthy sentiment no doubt - the idea that every citizen have as much agency and human capital as possible.

Yet the reality is that millions of Americans will spend their lives in low-wage, low-skill, low-status jobs. They are essential to our modern economy, in that there is a large portion of the citizenry with low enough levels of human and societal (H/S) capital that they will, in a practical sense, have no other option than to work in these occupations. Many of these jobs are not essential - gardening, house cleaning, nannying for two-parent families, washing cars, etc. But many of them are - janitorial services, cashiers, home health workers, etc. If these jobs are the "behavioral incentive" for the rest of us to pursue more skilled, higher status and better paying employment, they are also the actual jobs that millions of Americans must work in order to support themselves and their families.

It is a convenient story to tell ourselves - especially as we avail ourselves of their cheap labor, no thought to the implications of this relationship on their family, their health, the career prospects of their children, etc. - but it relies on the subjugation, disenfranchisement and exploitation of millions. These are the families that live in the poorest communities, go to the poorest schools, and suffer the worst of our social problems.

If this sort of existence is so dreadful, so as to serve as the launching pad of our economic engine, that dreadful gravity so despicable we'll go to any lengths to reach its escape velocity, to propel not only our own growth but that of society - of civilization itself, it is an existence that would therefor seem required. For, what if these jobs were compensated more fairly, thus likely regaining some status in the process. What if instead of $8 dollars an hour, a gardener was receiving $24, able to choose where he wanted to live, pay all his bills, open a savings account, and pay for healthcare for his family?

What effect would this have on individual striving? What effect on economic growth overall? Would many of us forgo college or advanced technical training for the prospect of simple, well-compensated service work? Non-essential services like gardening would no doubt become more rarefied as they would become a less affordable market.

The deeper question we need to ask is what is it that drives some individuals into low-SES work, and others into higher-SES work. It simply isn't the case that every citizen has the same odds of entering either occupation. Demographics play an enormous role, as I have discussed the concepts of human and societal capital at length on this blog. The societal capital one is born into is enormously determinative.

So on the one hand you have the theory of SES incentive as a driver of life success. Yet on the other, you have the fact that this incentive appears to operate quite differently across demographics. How could this be? If it were the most important determining factor, you would see little demographic effect. So it seems clearly to be of marginal importance. No one dreams of being a gardener or maid - certainly not the students I have taught whose parents were employed thusly. In fact, they tended to be quite angry and rebellious, feeling, yet likely not understanding in a very comprehensive way, the very real sense that society was exploiting their family.

One might think that this would create in them an even stronger incentive to gain more skills than their parents, so as to acquire a job with better pay and higher status. After all, they were living the example of why these jobs are to be avoided. Yet interestingly, their feelings were more complex. For one, they were surrounded since birth by those with a similarly low-SES. From their family to their neighbors, to their school peers, they were exposed to a lack of high-SES examples. None of their parents were doctors or lawyers or teachers or successful business owners. It therefore become more normal to expect less from life. As much as they were exposed to examples of the reality of low-pay and low-status, they were also exposed to human resilience and transcendence. They found ways to achieve status that were defined not by larger social norms - which were outside their immediate grasp - but that could be defined within the community.

If they were not going to get respect from society - which, it must be said, had a racial component, namely "whiteness" - they were going to enforce and maintain it within their peer groups and community. Juan's mom may have only been a maid for a "rich white lady", but Juan was going to have a bad-ass truck with pimped out speakers. In this way, low-status work enforces social norms that acquire status through non-traditional, "outsider" means. Among low income whites, these norms are going to be less radical than the "white" norms of larger society. Yet among low income minorities, these "white" norms are going to be seen as less accessible, and furthermore resented as historical barriers to acquisition of status.

The concept of low-SES being a social good, as a promoter of incentive towards higher productivity is a convenient myth. It sounds good, especially as a salve for our conscience as we engage in a marketplace that exploits low-SES workers. But it is an ad-hoc construct with little evidence to back up its central claim of net benefit to human agency. Instead, it undermines opportunity and social mobility by creating an economically and socially segregated caste of workers from which few escape. It promotes not social mobility but generational poverty by depleting societal and human capital.

By all measures, Jaime and Maria represent the lower end of inequality; their reward for their hard work is in no way equal to the rewards earned by the affluent. Yet, there a creepy argument on the right that this sort of inequality is actually good for society. It provides an incentive for people to strive and be more productive. The low pay and devaluing of certain jobs actually function as an inspiration to social mobility. No one wants to earn low pay for low-status work - especially work that is back breaking and mind-numbing. Therefore, these jobs act as behavioral reinforcers of productive economic activity, investments in one's skill-level and striving for a better life. How can one strive for what is "better" if there is no "better"?

This narrative is deeply embedded in our national political conversation. It is to some extent true. Those of us who are not low-skill, low-wage, low-status workers, we are glad we are not and no doubt at some point in our life made a conscious decision to not wind up as one. We like to tell ourselves that we are "deserving" of our higher wages and status because of our merit, the skill we have acquired that allows us to offer more than arms to dig or clean with. In many ways, there is a strong correlation between pay and merit, in the sense that the more one has to offer, the more one is compensated for it. As an educator and parent, forefront in my mind has been the future career prospects of my students and children. A hallmark rallying cry of public education in the past decade has been that "every child have the opportunity to go to college". A worthy sentiment no doubt - the idea that every citizen have as much agency and human capital as possible.

Yet the reality is that millions of Americans will spend their lives in low-wage, low-skill, low-status jobs. They are essential to our modern economy, in that there is a large portion of the citizenry with low enough levels of human and societal (H/S) capital that they will, in a practical sense, have no other option than to work in these occupations. Many of these jobs are not essential - gardening, house cleaning, nannying for two-parent families, washing cars, etc. But many of them are - janitorial services, cashiers, home health workers, etc. If these jobs are the "behavioral incentive" for the rest of us to pursue more skilled, higher status and better paying employment, they are also the actual jobs that millions of Americans must work in order to support themselves and their families.

It is a convenient story to tell ourselves - especially as we avail ourselves of their cheap labor, no thought to the implications of this relationship on their family, their health, the career prospects of their children, etc. - but it relies on the subjugation, disenfranchisement and exploitation of millions. These are the families that live in the poorest communities, go to the poorest schools, and suffer the worst of our social problems.

If this sort of existence is so dreadful, so as to serve as the launching pad of our economic engine, that dreadful gravity so despicable we'll go to any lengths to reach its escape velocity, to propel not only our own growth but that of society - of civilization itself, it is an existence that would therefor seem required. For, what if these jobs were compensated more fairly, thus likely regaining some status in the process. What if instead of $8 dollars an hour, a gardener was receiving $24, able to choose where he wanted to live, pay all his bills, open a savings account, and pay for healthcare for his family?

What effect would this have on individual striving? What effect on economic growth overall? Would many of us forgo college or advanced technical training for the prospect of simple, well-compensated service work? Non-essential services like gardening would no doubt become more rarefied as they would become a less affordable market.

The deeper question we need to ask is what is it that drives some individuals into low-SES work, and others into higher-SES work. It simply isn't the case that every citizen has the same odds of entering either occupation. Demographics play an enormous role, as I have discussed the concepts of human and societal capital at length on this blog. The societal capital one is born into is enormously determinative.

So on the one hand you have the theory of SES incentive as a driver of life success. Yet on the other, you have the fact that this incentive appears to operate quite differently across demographics. How could this be? If it were the most important determining factor, you would see little demographic effect. So it seems clearly to be of marginal importance. No one dreams of being a gardener or maid - certainly not the students I have taught whose parents were employed thusly. In fact, they tended to be quite angry and rebellious, feeling, yet likely not understanding in a very comprehensive way, the very real sense that society was exploiting their family.

One might think that this would create in them an even stronger incentive to gain more skills than their parents, so as to acquire a job with better pay and higher status. After all, they were living the example of why these jobs are to be avoided. Yet interestingly, their feelings were more complex. For one, they were surrounded since birth by those with a similarly low-SES. From their family to their neighbors, to their school peers, they were exposed to a lack of high-SES examples. None of their parents were doctors or lawyers or teachers or successful business owners. It therefore become more normal to expect less from life. As much as they were exposed to examples of the reality of low-pay and low-status, they were also exposed to human resilience and transcendence. They found ways to achieve status that were defined not by larger social norms - which were outside their immediate grasp - but that could be defined within the community.

If they were not going to get respect from society - which, it must be said, had a racial component, namely "whiteness" - they were going to enforce and maintain it within their peer groups and community. Juan's mom may have only been a maid for a "rich white lady", but Juan was going to have a bad-ass truck with pimped out speakers. In this way, low-status work enforces social norms that acquire status through non-traditional, "outsider" means. Among low income whites, these norms are going to be less radical than the "white" norms of larger society. Yet among low income minorities, these "white" norms are going to be seen as less accessible, and furthermore resented as historical barriers to acquisition of status.

The concept of low-SES being a social good, as a promoter of incentive towards higher productivity is a convenient myth. It sounds good, especially as a salve for our conscience as we engage in a marketplace that exploits low-SES workers. But it is an ad-hoc construct with little evidence to back up its central claim of net benefit to human agency. Instead, it undermines opportunity and social mobility by creating an economically and socially segregated caste of workers from which few escape. It promotes not social mobility but generational poverty by depleting societal and human capital.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Romney/conservatives think liberals over-emphasize the importance of government. Obama/liberals think conservatives underestimate importance of government.

I suppose in the end all of this stuff, marginal as it appears at the time, nibbles away into the formation of political movements over the decades. But in the moment, it all feels a bit too much like we're all caught in a sort of molasses-like political ether in which much of what we communicate to one another is merely an expression of larger, intangible forces.