Maybe it was the release of Charles Murray's latest book - which is not about race! Or the recent firing of John Derbyshire. Or the continued failure of NCLB to show much progress at all. Or maybe just that we have a black president. But paleo-conservativism seems to be getting bullish on the political incorrect notions of genetic and racial explanations of social inequality.

As I have written before, there is an enormous degree of correlation

between the acceptance of right wing assumptions and the acceptance of genetic explanations for race and socioeconomics. Because of the

unconscious nature of how racism tends to operate, it is therefore

appropriate to ask how much right wing assumptions are actually

facilitating acceptance of racist frameworks for socioeconomic analysis.

It is easy to see why. The right wing framing generally sees social

class as meritocratic and fair. Yet the continued disproportionate

representation of blacks among the lower-SES strata presents a problem that

needs to be explained. The three general categories of answer are

1) genetic, 2) environmental, and 3) personal choice. Because of our

history of racism, civil society shies away from genetic explanations.

The left wing, comfortable with subverting traditional power structures

and state intervention in social environments, tends toward

environmental explanations.

The right, to the degree that it opposes social redistribution or

state intervention, is challenged to propose its own solutions.

Generally, it adopts the personal choice model; even though it accepts

some of the environmental explanations (who could deny so much

research?), as a practical matter - to the degree that we value justice

- it argues for the metaphysical existence of an individual's power to

transcend environmental limitations. This isn't actually supported by

social research, but it apparently has great intuitive and rhetorical

power.

Another choice, one favored by right-leaning individuals, is to be "politically incorrect", and adopt the

genetic explanation. The IQ-SES framing adopts the genetic explanation,

with higher IQs in positions of power, and lower IQs in position of

subordinance. While intuitively "icky", this explanation at least

removes the burden of having to explain stubborn patterns of racial and

socioeconomic inequality in environmental or personal choice terms.

Of course, as with right wing claims about personal choice and the effects of environment on development, claims about the existence of a genetic meritocracy aren't supported by the research. Sure, you can always find research that agrees with you. But like evolution or global warming, the research is poorly designed and rejected by a large consensus of experts in the relevant fields.

Yet given the troubling persistence of unscientific views on the right (far more representative of majority opinion than unscientific views on the left), one wonders whether genetic explanations of socioeconomics and race will begin to become more acceptable in conservative circles, and among the base of the Republican party?

A bastard's take on human behavior, politics, religion, social justice, family, race, pain, free will, and trees

Sunday, April 29, 2012

Sunday, April 22, 2012

Compensation & Ideals

In the capitalist system, labor is generally payed for out of the difference between profit from the consumer and compensation to the employer. In other words, if a businessman can spend $1 on materials and sell a widget for $5, he has $4 with which to pay the worker and himself. Just as there is a larger competitive market within he must sell his widget, so to is there a larger competitive market within which he must hire his workers. If the going rate for assembling widgets is $10 an hour, he must work within some rough margin of that number.

The market for wages can often seem highly unfair. Backbreaking labor is often rewarded very poorly, while relatively comfortable labor is rewarded highly. By what mechanisms does this occur?

This is a question that has always perplexed me: To what degree is compensation related to skill (investment in training), value, sheer difficulty, and then of course, social rank?

The really creepy thing in this equation is the degree to which one's position is socially determined, having to do with privilege of human and societal capital. The free marketeer would argue the market is an objective arbiter of what is fair. Yet a more sophisticated mind would acknowledge the multiple ways in which the market merely enforces inherited privileges reinforced through institutional norms.

Regarding acquisition of skill via college vs. trade, the bias towards social rank has no doubt something to do with how we perceive the value-added component of college. In other words, the attainment of knowledge outside a specific skill-set is thought of as worth something to society apart from labor value. In this way, does college's conferral of social rank represent an enforcement of enlightenment as a social norm, rewarding those who pursue this value so as to uphold its continued social aspiration?

Or is this a story we, the college-educated elite tell ourselves? I for one admit my bias - I consider my time in college as foundational to how I have learned to think about the world. I have been exposed to the highest traditions of civilized thought. I can't help but imagine that had I not gone to college, I would be a lesser man for it. How can I not be biased then against those who have not gone to college, at least in terms of a general lack of contextual knowledge and or critical thinking skills. Let me put it to you this way: one is a better man for having read Plato and Marx, and engaged in its critical analysis. There may be no direct correlation to a specific workplace skill, but there is no doubt that one's mind is at least marginally better at understanding the world and better contributing to it.

So again, is the added compensation for a college degree to some extent enforcing this broad social value of the expansive mind?

The market for wages can often seem highly unfair. Backbreaking labor is often rewarded very poorly, while relatively comfortable labor is rewarded highly. By what mechanisms does this occur?

This is a question that has always perplexed me: To what degree is compensation related to skill (investment in training), value, sheer difficulty, and then of course, social rank?

The really creepy thing in this equation is the degree to which one's position is socially determined, having to do with privilege of human and societal capital. The free marketeer would argue the market is an objective arbiter of what is fair. Yet a more sophisticated mind would acknowledge the multiple ways in which the market merely enforces inherited privileges reinforced through institutional norms.

Regarding acquisition of skill via college vs. trade, the bias towards social rank has no doubt something to do with how we perceive the value-added component of college. In other words, the attainment of knowledge outside a specific skill-set is thought of as worth something to society apart from labor value. In this way, does college's conferral of social rank represent an enforcement of enlightenment as a social norm, rewarding those who pursue this value so as to uphold its continued social aspiration?

Or is this a story we, the college-educated elite tell ourselves? I for one admit my bias - I consider my time in college as foundational to how I have learned to think about the world. I have been exposed to the highest traditions of civilized thought. I can't help but imagine that had I not gone to college, I would be a lesser man for it. How can I not be biased then against those who have not gone to college, at least in terms of a general lack of contextual knowledge and or critical thinking skills. Let me put it to you this way: one is a better man for having read Plato and Marx, and engaged in its critical analysis. There may be no direct correlation to a specific workplace skill, but there is no doubt that one's mind is at least marginally better at understanding the world and better contributing to it.

So again, is the added compensation for a college degree to some extent enforcing this broad social value of the expansive mind?

Saturday, April 21, 2012

Watching People Talk

Keith Humphreys proposes that great Hollywood dialogue has been in decline for a long time. He mentions Sorkin and the Coen brothers as exceptions.

Sorkin's dialogue has always irritated me. I've never been quite able to put my finger on it, and I'm not dextrous enough with my understanding of writing to properly critique it. There are many styles of dialogue, and I suppose you could define a spectrum with realism on one end and - here my ignorance limits me - a sort of heavily laden, poetic, - I'll just call it the "expository style", in which the character is as much a sort of avatar for larger expression. I don't mean to demean it as a reduction to exposition in the classic sense, but rather as a style that is exposing some idea, or emotion, or otherwise narrative that would not be conveyed by mere realism. I'm not opposed to this. In great hands it is sublime, if demanding of the audience. Many of Shakespeare's character's I imagine represent the ultimate form of this sort of character-as-vessel style.

At the other end, realism allows for an intimacy and immediacy that can transcend its limitations and capture as much if not more poetry and truth. As a style it also seems to work so much better on film, as close-ups and environmental realism allow us to develop so much more intimacy and transported experience. A Shakespearean or Sorkin soliloquy isn't ever going to reach places that the audience can be taken to through the sensory richness and purely subjective experience of something like getting the gesture of a hand just right as it nervously taps out a cigarette, or the protagonist's solemn commute in the front seat of a deteriorating station wagon. Dialogue in such settings needs to not get in the way of what is being conveyed elsewhere in the film - the set, the light, the costume, the acting, etc.

In the end, I may just prefer realism more than the "exposition style". But this may owe more to it being done well less often. And I think when it fails it does so miserably. It comes off as forced and clunky, or, worst of all, clumsily representative of the writer's own pedantic narcissism, baldly scoring points through the characters' showy demonstration of wit, audacity, brilliance, or some other superlative skill carefully slaved over line by line, yet flowing from the actor as if the most natural thing in the world. I felt this way about Juno, and about The West Wing. The former in the character's precocious rebellion, the latter in wonk after wonks' wankery.

If ambitious dialogue has been in decline, I wonder why? Have we - our tastes - changed? Has the medium's change contributed. Plenty out there would have much more interesting to say than I. It's a fascinating question.

Sorkin's dialogue has always irritated me. I've never been quite able to put my finger on it, and I'm not dextrous enough with my understanding of writing to properly critique it. There are many styles of dialogue, and I suppose you could define a spectrum with realism on one end and - here my ignorance limits me - a sort of heavily laden, poetic, - I'll just call it the "expository style", in which the character is as much a sort of avatar for larger expression. I don't mean to demean it as a reduction to exposition in the classic sense, but rather as a style that is exposing some idea, or emotion, or otherwise narrative that would not be conveyed by mere realism. I'm not opposed to this. In great hands it is sublime, if demanding of the audience. Many of Shakespeare's character's I imagine represent the ultimate form of this sort of character-as-vessel style.

At the other end, realism allows for an intimacy and immediacy that can transcend its limitations and capture as much if not more poetry and truth. As a style it also seems to work so much better on film, as close-ups and environmental realism allow us to develop so much more intimacy and transported experience. A Shakespearean or Sorkin soliloquy isn't ever going to reach places that the audience can be taken to through the sensory richness and purely subjective experience of something like getting the gesture of a hand just right as it nervously taps out a cigarette, or the protagonist's solemn commute in the front seat of a deteriorating station wagon. Dialogue in such settings needs to not get in the way of what is being conveyed elsewhere in the film - the set, the light, the costume, the acting, etc.

In the end, I may just prefer realism more than the "exposition style". But this may owe more to it being done well less often. And I think when it fails it does so miserably. It comes off as forced and clunky, or, worst of all, clumsily representative of the writer's own pedantic narcissism, baldly scoring points through the characters' showy demonstration of wit, audacity, brilliance, or some other superlative skill carefully slaved over line by line, yet flowing from the actor as if the most natural thing in the world. I felt this way about Juno, and about The West Wing. The former in the character's precocious rebellion, the latter in wonk after wonks' wankery.

If ambitious dialogue has been in decline, I wonder why? Have we - our tastes - changed? Has the medium's change contributed. Plenty out there would have much more interesting to say than I. It's a fascinating question.

Is McDonalds the Opiate of the Poor?

Apparently "food deserts" - neighborhoods lacking in access to quality groceries - don't have as much to do with obesity as some thought. Kevin Drum has an interesting piece up trying to disentangle the results from some recent studies on the issue. One study finds that "Access to different kinds of stores didn't have any impact on weight gain among elementary-school-aged children". From another, "Obesity rates among supermarket shoppers closely tracked both food

prices and incomes," he found, but not the kinds of food available.

Shoppers at  Albertson's,

a low-cost chain, were far more obese than shoppers at Whole Foods,

even though both provided plenty of access to fresh fruits and

vegetables." Another study of 13,000 California kids found "no relationship between what type of food students said

they ate, what they weighed, and the type of food within a mile and a

half of their homes…Living close to supermarkets or grocers did not make

students thin and living close to fast food outlets did not make them

fat."

Albertson's,

a low-cost chain, were far more obese than shoppers at Whole Foods,

even though both provided plenty of access to fresh fruits and

vegetables." Another study of 13,000 California kids found "no relationship between what type of food students said

they ate, what they weighed, and the type of food within a mile and a

half of their homes…Living close to supermarkets or grocers did not make

students thin and living close to fast food outlets did not make them

fat."

The Mother Jones comments to the piece are illustrative of what I think is an interesting picture of how liberals tend to perceive poverty. On the one hand, you have people dismissing the findings, claiming that it all comes down to price: that poor people simply can't afford quality foods, even when offered. This assumes that there is a nutritional consciousness, but that it is overcome by economic realities. On the other hand, you have people saying that there is no nutritional consciousness, that the problem is due to a lack of the requisite knowledge to discern healthy from unhealthy diets.

Between these competing narratives, you have a tension between not wanting to blame poor people and assuming that their choices are rational, and trying to explain poor choices in the context of lack of education.

It is a fascinating discussion, and there aren't any easy answers. Poor people clearly tend to make more poor choices. But to what extent are these choices unavoidable, and to what extent do they represent a lack of education? The term consciousness is interesting, because it encompasses both what might be a lack of education, or world-knowledge, as well as lack of self-knowledge. For instance, one might know that food A is better for you (world-knowledge), but feel compelled to choose food B, a less healthier, yet more immediately satisfying choice. The degree to which one gives in to temptation is partly due to an understanding of one's good vs. bad habits (self-knowledge).

Now, this second aspect of consciousness - self-knowledge - is tricky. It is very difficult to disentangle to what extent one's conscious perception is based on prior habits, and how much it is being directly influenced by environmental factors. We all struggle at times to eat healthy. Yet after a long, stressful day at work, the struggle becomes much more difficult. This is especially true when one feels as though the unhealthy yet highly-craved choice is felt to be a sort of reward, as in, "My day was so hard - I deserve this." In this sense, the choice becomes rationalized as a form of justice. It isn't hard to imagine that the more one feels that their lot in life is unjust, that giving in to poor choices can seem justified.

I'm reminded of an incredibly interesting study done on the behavior of rats and their seeming sense of justice and motivation. Unfortunately, I've searched in vain for a link. But from memory, apparently it was found that when rats were placed within viewing distance of other rats, their motivation decreased significantly when they observed inequity in reward. Other research in non-humans has found similar evidence: inequity and unfairness tends to create anger and resentment. It makes sense that this would at the very least create stress. And there is much evidence that stress leads to compensatory, pleasure-inducing mechanisms of self-stimulation to recapture dopamine. When all else fails, eat a candy bar.

This is a Marxist analysis, so it is only appropriate to paraphrase Marx in asking whether low-nutrition, high-pleasure foods are the opiates of the masses.

Albertson's,

a low-cost chain, were far more obese than shoppers at Whole Foods,

even though both provided plenty of access to fresh fruits and

vegetables." Another study of 13,000 California kids found "no relationship between what type of food students said

they ate, what they weighed, and the type of food within a mile and a

half of their homes…Living close to supermarkets or grocers did not make

students thin and living close to fast food outlets did not make them

fat."

Albertson's,

a low-cost chain, were far more obese than shoppers at Whole Foods,

even though both provided plenty of access to fresh fruits and

vegetables." Another study of 13,000 California kids found "no relationship between what type of food students said

they ate, what they weighed, and the type of food within a mile and a

half of their homes…Living close to supermarkets or grocers did not make

students thin and living close to fast food outlets did not make them

fat."The Mother Jones comments to the piece are illustrative of what I think is an interesting picture of how liberals tend to perceive poverty. On the one hand, you have people dismissing the findings, claiming that it all comes down to price: that poor people simply can't afford quality foods, even when offered. This assumes that there is a nutritional consciousness, but that it is overcome by economic realities. On the other hand, you have people saying that there is no nutritional consciousness, that the problem is due to a lack of the requisite knowledge to discern healthy from unhealthy diets.

Between these competing narratives, you have a tension between not wanting to blame poor people and assuming that their choices are rational, and trying to explain poor choices in the context of lack of education.

It is a fascinating discussion, and there aren't any easy answers. Poor people clearly tend to make more poor choices. But to what extent are these choices unavoidable, and to what extent do they represent a lack of education? The term consciousness is interesting, because it encompasses both what might be a lack of education, or world-knowledge, as well as lack of self-knowledge. For instance, one might know that food A is better for you (world-knowledge), but feel compelled to choose food B, a less healthier, yet more immediately satisfying choice. The degree to which one gives in to temptation is partly due to an understanding of one's good vs. bad habits (self-knowledge).

Now, this second aspect of consciousness - self-knowledge - is tricky. It is very difficult to disentangle to what extent one's conscious perception is based on prior habits, and how much it is being directly influenced by environmental factors. We all struggle at times to eat healthy. Yet after a long, stressful day at work, the struggle becomes much more difficult. This is especially true when one feels as though the unhealthy yet highly-craved choice is felt to be a sort of reward, as in, "My day was so hard - I deserve this." In this sense, the choice becomes rationalized as a form of justice. It isn't hard to imagine that the more one feels that their lot in life is unjust, that giving in to poor choices can seem justified.

I'm reminded of an incredibly interesting study done on the behavior of rats and their seeming sense of justice and motivation. Unfortunately, I've searched in vain for a link. But from memory, apparently it was found that when rats were placed within viewing distance of other rats, their motivation decreased significantly when they observed inequity in reward. Other research in non-humans has found similar evidence: inequity and unfairness tends to create anger and resentment. It makes sense that this would at the very least create stress. And there is much evidence that stress leads to compensatory, pleasure-inducing mechanisms of self-stimulation to recapture dopamine. When all else fails, eat a candy bar.

This is a Marxist analysis, so it is only appropriate to paraphrase Marx in asking whether low-nutrition, high-pleasure foods are the opiates of the masses.

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

An Ugly Marriage

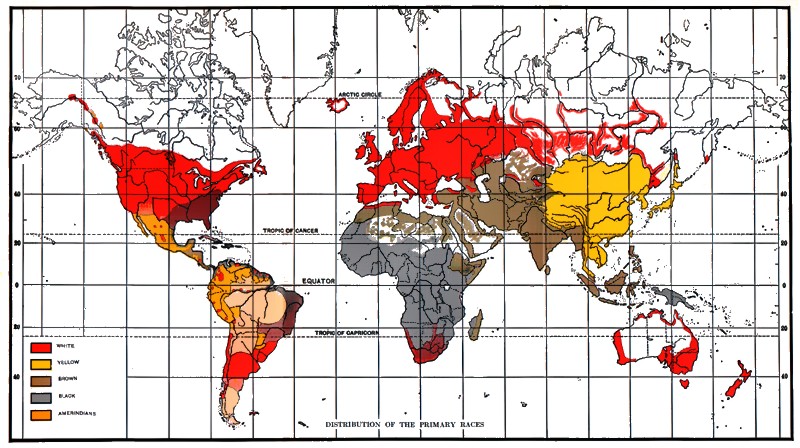

|

| "Race Map" from 1920 |

My interest piqued by the title, I was struck however by this bit from the synopsis on Amazon,

"Weissberg argues that most of America's educational woes would vanishI then noticed that this was followed by a favorable blurb from none other than John Derbyshire, the conservative columnist for the National Review who was recently fired after achieving infamy in a column in which he pretended (?) to give advice to his white child on how to avoid various threats black people might pose - a racist version of "the talk", the much publicized response amid furor over the George Zimmerman profiling case many black parents have felt necessary giving their children. Here's a little taste:

if indifferent, troublesome students were permitted to leave when they

had absorbed as much as they could learn; they would quickly be replaced

by learning-hungry students, including many new immigrants from other

countries."

...Thus, while always attentive to the particular qualities of individuals, on the many occasions where you have nothing to guide you but knowledge of those mean differences, use statistical common sense:In my last podcast, I pointed to the fact that racists always seem to be conservative. I argued that this is likely due at least in part to the substantive claims conservatism makes. While its logic does not unavoidably lead to racism, its underlying assumptions do much of the logical heavy-lifting. Taking a spin around the site that hosted Derbyshire's writing, the racism is as close to explicit as it gets. And the list of contributors is paleo-conservative to the bone. You can almost hear the brandy glasses clinking in the background as the phrenology calipers are adjusted.

(10a) Avoid concentrations of blacks not all known to you personally.

(10b) Stay out of heavily black neighborhoods.

(10c) If planning a trip to a beach or amusement park at some date, find out whether it is likely to be swamped with blacks on that date (neglect of that one got me the closest I have ever gotten to death by gunshot)....

(11) The mean intelligence of blacks is much lower than for whites. The least intelligent ten percent of whites have IQs below 81; forty percent of blacks have IQs that low. Only one black in six is more intelligent than the average white; five whites out of six are more intelligent than the average black. These differences show in every test of general cognitive ability that anyone, of any race or nationality, has yet been able to devise. They are reflected in countless everyday situations. “Life is an IQ test.”

One might dismiss these radical types as not representative of any larger conservative movement. And to an extent that is no doubt true. Yet while most prominent conservatives would have a hard time coming right out so bluntly, it isn't hard to see how such thinking represents a mere coherence of the nebulous, uncomfortability conservatism has with race and class in general. In a tragic way, race acts as a kind of litmus test for the poisoned waters of "meritocracy", the sly fantasy the right-wing embraces as a means of perpetuating traditional power structures. In a sea of undifferentiated masses, it is easier to pretend that the poor are merely choosing their own sorry destitution. Yet when poverty remains so wedded to race and ethnicity, it becomes hard not to seek explanations either in social structures or genetics. As embracing radical change in social hierarchies is anathema to conservatism, radical paleo-conservatives are merely being honest when they voice their preference to adopt genetic explanations.

Milton Friedman, in his 1980 miniseries Free to Choose

I'm fascinated by the politics of education reform, and the lenses that it gets viewed through. I do agree that the problem is the students, and demographics - you can't argue with facts. But where I differ is that I see this not as a problem of racial or ethnic inferiority, but as one perpetuated by our economic and social system, where human and societal capital are distributed according to privilege.

I see current reform efforts ultimately as a clever alliance between this kind of paleo-conservative racial & class exclusion and neo-liberal naivete that wants to believe that poor kids' only enemy is bad teaching. Vouchers have been replaced by charter schools, which promise to give both groups what they think they want.

Unfortunately, the problem - for those of us neither right-wing racialists, nor pie-in-the-sky teacher demagogues - is about equality of opportunity. If we really want to give kids an equal education, we need to invest in levels of service appropriate to the necessary intervention. That, we have not yet begun.

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

But What Kind of Collaboration?

A recent article in the Atlantic emphasizes the need for more collaboration among teachers in schools.

Saturday, April 14, 2012

A Difference in Framing

Non-reformer writes: "Because we know that poorly educated parents and poverty are the root causes of poor achievement."

Reformer responds: "We don't know that at all. In fact, all historical and global evidence would completely contradict that hypothesis. What we know is that poor children in the U.S. are not educated well within the U.S. public education system."

Curiously, if one could sum up the education Reform mindset, it might come down to this difference in framing. Reformers tend to want to diminish the effects of SES, and emphasize teacher efficacy. The response from Non-reformers is generally to push back and emphasize SES. The Reformer often calls this "making excuses", famously "the soft bigotry of low expectations". The term reform itself has become loaded as it sets up one particular framework as being reform, and anything else as, well, non-reform. And when everyone agrees the education system is broken, the non-reformer becomes defined by an implication that they support the system as it stands.

Non-reformer responds: "Of course it is not poverty itself that affects learning but the EFFECTS of poverty ...."

However, most Non-reformers I know (which also happens to be most teachers and non-teachers), actually want even greater reforms to education. They don't see teachers as the problem, but larger social problems. They point to all the things the Non-refomer referred to - the EFFECTS - of poverty as being what we need to reform.

Now, part of the difference in frameworks might have to do with a broader sort of political temperament. Reformers have been so successful because they have built a coalition of conservatives and neo-liberals. As a group, a common feature is a tendency away from radical, progressivism. Yet this is exactly what non-reformers would champion.

The reality is of course, that the public is in no mood for radical progressivism. There is simply no political momentum toward an agenda of going after the EFFECTS (as Linda so succinctly put it) of poverty, which would require massive (OK, *cough* I use this term relatively! "Imagine if they had to have a bake sale...") state spending.

So the neo-liberal model, biased as it is towards the political *possible*, essentially has thrown in the towel on looking at SES as the real reform and emphasizing instead the marginal benefits of squeezing more achievement out of teachers. Unfortunately, the result has been so good. I realize my bias as a non-reformer, but there just doesn't seem to be much evidence that union-busting, charters, performance-pay, punitive testing, etc. has really done much at all.

Non-reformers would say, of course, "See. I told you so." And the system has been really screwed up. Teachers feel completely demoralized, their jobs as un-meaningful as ever, expectations higher than ever yet their tasks only more daunting, humanity removed from the profession and countless punitive professional development sessions and administrators forced by their bosses into a bizarro world that fundamentally misunderstands the classroom.

Personally, I think all this "reform", based as much of it has been on an attempt to find consensus and work within political realities has not only made the system worse, but has moved the debate away from where it really should be. To use an analogy, it would be as a bus were speeding towards you and instead of jumping out of the way, you start running in the opposite direction, hoping it won't catch up. Well, I think it's finally caught up.

Reformers talk about making "excuses". However, I would argue it is they who are the real excuse-makers. By constantly shifting the blame away from larger, more serious social problems, they excuse them. The reality is that the achievement gap is based on a fundamental reality: SES means human and societal capital. The advantaged have a lot more of it than the disadvantaged. Reformers would have us believe that this inequality can be overcome simply by "better teaching". They would have us believe that teachers in a poor community should be expected to work twice as hard - be twice as good - as teachers in affluent communities.

Yet in the end, what this tells poor communities is that, despite your lower levels of human and societal capital, we're not going to give you any more support. We're going to force to to rely on the same teaching pool as everyone else, even though your needs are so much more profound. Imagine if we did this with police departments. What if every neighborhood only got a limited number of service calls, then we blamed the police for the rise in crime rates?

That isn't reform. It's perpetuation of social inequality by a privileged class who doesn't want to sacrifice for those less fortunate. It's also a betrayal of what public education has always been about.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)