Maybe it was the release of Charles Murray's latest book - which is not about race! Or the recent firing of John Derbyshire. Or the continued failure of NCLB to show much progress at all. Or maybe just that we have a black president. But paleo-conservativism seems to be getting bullish on the political incorrect notions of genetic and racial explanations of social inequality.

As I have written before, there is an enormous degree of correlation

between the acceptance of right wing assumptions and the acceptance of genetic explanations for race and socioeconomics. Because of the

unconscious nature of how racism tends to operate, it is therefore

appropriate to ask how much right wing assumptions are actually

facilitating acceptance of racist frameworks for socioeconomic analysis.

It is easy to see why. The right wing framing generally sees social

class as meritocratic and fair. Yet the continued disproportionate

representation of blacks among the lower-SES strata presents a problem that

needs to be explained. The three general categories of answer are

1) genetic, 2) environmental, and 3) personal choice. Because of our

history of racism, civil society shies away from genetic explanations.

The left wing, comfortable with subverting traditional power structures

and state intervention in social environments, tends toward

environmental explanations.

The right, to the degree that it opposes social redistribution or

state intervention, is challenged to propose its own solutions.

Generally, it adopts the personal choice model; even though it accepts

some of the environmental explanations (who could deny so much

research?), as a practical matter - to the degree that we value justice

- it argues for the metaphysical existence of an individual's power to

transcend environmental limitations. This isn't actually supported by

social research, but it apparently has great intuitive and rhetorical

power.

Another choice, one favored by right-leaning individuals, is to be "politically incorrect", and adopt the

genetic explanation. The IQ-SES framing adopts the genetic explanation,

with higher IQs in positions of power, and lower IQs in position of

subordinance. While intuitively "icky", this explanation at least

removes the burden of having to explain stubborn patterns of racial and

socioeconomic inequality in environmental or personal choice terms.

Of course, as with right wing claims about personal choice and the effects of environment on development, claims about the existence of a genetic meritocracy aren't supported by the research. Sure, you can always find research that agrees with you. But like evolution or global warming, the research is poorly designed and rejected by a large consensus of experts in the relevant fields.

Yet given the troubling persistence of unscientific views on the right (far more representative of majority opinion than unscientific views on the left), one wonders whether genetic explanations of socioeconomics and race will begin to become more acceptable in conservative circles, and among the base of the Republican party?

A bastard's take on human behavior, politics, religion, social justice, family, race, pain, free will, and trees

Sunday, April 29, 2012

Sunday, April 22, 2012

Compensation & Ideals

In the capitalist system, labor is generally payed for out of the difference between profit from the consumer and compensation to the employer. In other words, if a businessman can spend $1 on materials and sell a widget for $5, he has $4 with which to pay the worker and himself. Just as there is a larger competitive market within he must sell his widget, so to is there a larger competitive market within which he must hire his workers. If the going rate for assembling widgets is $10 an hour, he must work within some rough margin of that number.

The market for wages can often seem highly unfair. Backbreaking labor is often rewarded very poorly, while relatively comfortable labor is rewarded highly. By what mechanisms does this occur?

This is a question that has always perplexed me: To what degree is compensation related to skill (investment in training), value, sheer difficulty, and then of course, social rank?

The really creepy thing in this equation is the degree to which one's position is socially determined, having to do with privilege of human and societal capital. The free marketeer would argue the market is an objective arbiter of what is fair. Yet a more sophisticated mind would acknowledge the multiple ways in which the market merely enforces inherited privileges reinforced through institutional norms.

Regarding acquisition of skill via college vs. trade, the bias towards social rank has no doubt something to do with how we perceive the value-added component of college. In other words, the attainment of knowledge outside a specific skill-set is thought of as worth something to society apart from labor value. In this way, does college's conferral of social rank represent an enforcement of enlightenment as a social norm, rewarding those who pursue this value so as to uphold its continued social aspiration?

Or is this a story we, the college-educated elite tell ourselves? I for one admit my bias - I consider my time in college as foundational to how I have learned to think about the world. I have been exposed to the highest traditions of civilized thought. I can't help but imagine that had I not gone to college, I would be a lesser man for it. How can I not be biased then against those who have not gone to college, at least in terms of a general lack of contextual knowledge and or critical thinking skills. Let me put it to you this way: one is a better man for having read Plato and Marx, and engaged in its critical analysis. There may be no direct correlation to a specific workplace skill, but there is no doubt that one's mind is at least marginally better at understanding the world and better contributing to it.

So again, is the added compensation for a college degree to some extent enforcing this broad social value of the expansive mind?

The market for wages can often seem highly unfair. Backbreaking labor is often rewarded very poorly, while relatively comfortable labor is rewarded highly. By what mechanisms does this occur?

This is a question that has always perplexed me: To what degree is compensation related to skill (investment in training), value, sheer difficulty, and then of course, social rank?

The really creepy thing in this equation is the degree to which one's position is socially determined, having to do with privilege of human and societal capital. The free marketeer would argue the market is an objective arbiter of what is fair. Yet a more sophisticated mind would acknowledge the multiple ways in which the market merely enforces inherited privileges reinforced through institutional norms.

Regarding acquisition of skill via college vs. trade, the bias towards social rank has no doubt something to do with how we perceive the value-added component of college. In other words, the attainment of knowledge outside a specific skill-set is thought of as worth something to society apart from labor value. In this way, does college's conferral of social rank represent an enforcement of enlightenment as a social norm, rewarding those who pursue this value so as to uphold its continued social aspiration?

Or is this a story we, the college-educated elite tell ourselves? I for one admit my bias - I consider my time in college as foundational to how I have learned to think about the world. I have been exposed to the highest traditions of civilized thought. I can't help but imagine that had I not gone to college, I would be a lesser man for it. How can I not be biased then against those who have not gone to college, at least in terms of a general lack of contextual knowledge and or critical thinking skills. Let me put it to you this way: one is a better man for having read Plato and Marx, and engaged in its critical analysis. There may be no direct correlation to a specific workplace skill, but there is no doubt that one's mind is at least marginally better at understanding the world and better contributing to it.

So again, is the added compensation for a college degree to some extent enforcing this broad social value of the expansive mind?

Saturday, April 21, 2012

Watching People Talk

Keith Humphreys proposes that great Hollywood dialogue has been in decline for a long time. He mentions Sorkin and the Coen brothers as exceptions.

Sorkin's dialogue has always irritated me. I've never been quite able to put my finger on it, and I'm not dextrous enough with my understanding of writing to properly critique it. There are many styles of dialogue, and I suppose you could define a spectrum with realism on one end and - here my ignorance limits me - a sort of heavily laden, poetic, - I'll just call it the "expository style", in which the character is as much a sort of avatar for larger expression. I don't mean to demean it as a reduction to exposition in the classic sense, but rather as a style that is exposing some idea, or emotion, or otherwise narrative that would not be conveyed by mere realism. I'm not opposed to this. In great hands it is sublime, if demanding of the audience. Many of Shakespeare's character's I imagine represent the ultimate form of this sort of character-as-vessel style.

At the other end, realism allows for an intimacy and immediacy that can transcend its limitations and capture as much if not more poetry and truth. As a style it also seems to work so much better on film, as close-ups and environmental realism allow us to develop so much more intimacy and transported experience. A Shakespearean or Sorkin soliloquy isn't ever going to reach places that the audience can be taken to through the sensory richness and purely subjective experience of something like getting the gesture of a hand just right as it nervously taps out a cigarette, or the protagonist's solemn commute in the front seat of a deteriorating station wagon. Dialogue in such settings needs to not get in the way of what is being conveyed elsewhere in the film - the set, the light, the costume, the acting, etc.

In the end, I may just prefer realism more than the "exposition style". But this may owe more to it being done well less often. And I think when it fails it does so miserably. It comes off as forced and clunky, or, worst of all, clumsily representative of the writer's own pedantic narcissism, baldly scoring points through the characters' showy demonstration of wit, audacity, brilliance, or some other superlative skill carefully slaved over line by line, yet flowing from the actor as if the most natural thing in the world. I felt this way about Juno, and about The West Wing. The former in the character's precocious rebellion, the latter in wonk after wonks' wankery.

If ambitious dialogue has been in decline, I wonder why? Have we - our tastes - changed? Has the medium's change contributed. Plenty out there would have much more interesting to say than I. It's a fascinating question.

Sorkin's dialogue has always irritated me. I've never been quite able to put my finger on it, and I'm not dextrous enough with my understanding of writing to properly critique it. There are many styles of dialogue, and I suppose you could define a spectrum with realism on one end and - here my ignorance limits me - a sort of heavily laden, poetic, - I'll just call it the "expository style", in which the character is as much a sort of avatar for larger expression. I don't mean to demean it as a reduction to exposition in the classic sense, but rather as a style that is exposing some idea, or emotion, or otherwise narrative that would not be conveyed by mere realism. I'm not opposed to this. In great hands it is sublime, if demanding of the audience. Many of Shakespeare's character's I imagine represent the ultimate form of this sort of character-as-vessel style.

At the other end, realism allows for an intimacy and immediacy that can transcend its limitations and capture as much if not more poetry and truth. As a style it also seems to work so much better on film, as close-ups and environmental realism allow us to develop so much more intimacy and transported experience. A Shakespearean or Sorkin soliloquy isn't ever going to reach places that the audience can be taken to through the sensory richness and purely subjective experience of something like getting the gesture of a hand just right as it nervously taps out a cigarette, or the protagonist's solemn commute in the front seat of a deteriorating station wagon. Dialogue in such settings needs to not get in the way of what is being conveyed elsewhere in the film - the set, the light, the costume, the acting, etc.

In the end, I may just prefer realism more than the "exposition style". But this may owe more to it being done well less often. And I think when it fails it does so miserably. It comes off as forced and clunky, or, worst of all, clumsily representative of the writer's own pedantic narcissism, baldly scoring points through the characters' showy demonstration of wit, audacity, brilliance, or some other superlative skill carefully slaved over line by line, yet flowing from the actor as if the most natural thing in the world. I felt this way about Juno, and about The West Wing. The former in the character's precocious rebellion, the latter in wonk after wonks' wankery.

If ambitious dialogue has been in decline, I wonder why? Have we - our tastes - changed? Has the medium's change contributed. Plenty out there would have much more interesting to say than I. It's a fascinating question.

Is McDonalds the Opiate of the Poor?

Apparently "food deserts" - neighborhoods lacking in access to quality groceries - don't have as much to do with obesity as some thought. Kevin Drum has an interesting piece up trying to disentangle the results from some recent studies on the issue. One study finds that "Access to different kinds of stores didn't have any impact on weight gain among elementary-school-aged children". From another, "Obesity rates among supermarket shoppers closely tracked both food

prices and incomes," he found, but not the kinds of food available.

Shoppers at  Albertson's,

a low-cost chain, were far more obese than shoppers at Whole Foods,

even though both provided plenty of access to fresh fruits and

vegetables." Another study of 13,000 California kids found "no relationship between what type of food students said

they ate, what they weighed, and the type of food within a mile and a

half of their homes…Living close to supermarkets or grocers did not make

students thin and living close to fast food outlets did not make them

fat."

Albertson's,

a low-cost chain, were far more obese than shoppers at Whole Foods,

even though both provided plenty of access to fresh fruits and

vegetables." Another study of 13,000 California kids found "no relationship between what type of food students said

they ate, what they weighed, and the type of food within a mile and a

half of their homes…Living close to supermarkets or grocers did not make

students thin and living close to fast food outlets did not make them

fat."

The Mother Jones comments to the piece are illustrative of what I think is an interesting picture of how liberals tend to perceive poverty. On the one hand, you have people dismissing the findings, claiming that it all comes down to price: that poor people simply can't afford quality foods, even when offered. This assumes that there is a nutritional consciousness, but that it is overcome by economic realities. On the other hand, you have people saying that there is no nutritional consciousness, that the problem is due to a lack of the requisite knowledge to discern healthy from unhealthy diets.

Between these competing narratives, you have a tension between not wanting to blame poor people and assuming that their choices are rational, and trying to explain poor choices in the context of lack of education.

It is a fascinating discussion, and there aren't any easy answers. Poor people clearly tend to make more poor choices. But to what extent are these choices unavoidable, and to what extent do they represent a lack of education? The term consciousness is interesting, because it encompasses both what might be a lack of education, or world-knowledge, as well as lack of self-knowledge. For instance, one might know that food A is better for you (world-knowledge), but feel compelled to choose food B, a less healthier, yet more immediately satisfying choice. The degree to which one gives in to temptation is partly due to an understanding of one's good vs. bad habits (self-knowledge).

Now, this second aspect of consciousness - self-knowledge - is tricky. It is very difficult to disentangle to what extent one's conscious perception is based on prior habits, and how much it is being directly influenced by environmental factors. We all struggle at times to eat healthy. Yet after a long, stressful day at work, the struggle becomes much more difficult. This is especially true when one feels as though the unhealthy yet highly-craved choice is felt to be a sort of reward, as in, "My day was so hard - I deserve this." In this sense, the choice becomes rationalized as a form of justice. It isn't hard to imagine that the more one feels that their lot in life is unjust, that giving in to poor choices can seem justified.

I'm reminded of an incredibly interesting study done on the behavior of rats and their seeming sense of justice and motivation. Unfortunately, I've searched in vain for a link. But from memory, apparently it was found that when rats were placed within viewing distance of other rats, their motivation decreased significantly when they observed inequity in reward. Other research in non-humans has found similar evidence: inequity and unfairness tends to create anger and resentment. It makes sense that this would at the very least create stress. And there is much evidence that stress leads to compensatory, pleasure-inducing mechanisms of self-stimulation to recapture dopamine. When all else fails, eat a candy bar.

This is a Marxist analysis, so it is only appropriate to paraphrase Marx in asking whether low-nutrition, high-pleasure foods are the opiates of the masses.

Albertson's,

a low-cost chain, were far more obese than shoppers at Whole Foods,

even though both provided plenty of access to fresh fruits and

vegetables." Another study of 13,000 California kids found "no relationship between what type of food students said

they ate, what they weighed, and the type of food within a mile and a

half of their homes…Living close to supermarkets or grocers did not make

students thin and living close to fast food outlets did not make them

fat."

Albertson's,

a low-cost chain, were far more obese than shoppers at Whole Foods,

even though both provided plenty of access to fresh fruits and

vegetables." Another study of 13,000 California kids found "no relationship between what type of food students said

they ate, what they weighed, and the type of food within a mile and a

half of their homes…Living close to supermarkets or grocers did not make

students thin and living close to fast food outlets did not make them

fat."The Mother Jones comments to the piece are illustrative of what I think is an interesting picture of how liberals tend to perceive poverty. On the one hand, you have people dismissing the findings, claiming that it all comes down to price: that poor people simply can't afford quality foods, even when offered. This assumes that there is a nutritional consciousness, but that it is overcome by economic realities. On the other hand, you have people saying that there is no nutritional consciousness, that the problem is due to a lack of the requisite knowledge to discern healthy from unhealthy diets.

Between these competing narratives, you have a tension between not wanting to blame poor people and assuming that their choices are rational, and trying to explain poor choices in the context of lack of education.

It is a fascinating discussion, and there aren't any easy answers. Poor people clearly tend to make more poor choices. But to what extent are these choices unavoidable, and to what extent do they represent a lack of education? The term consciousness is interesting, because it encompasses both what might be a lack of education, or world-knowledge, as well as lack of self-knowledge. For instance, one might know that food A is better for you (world-knowledge), but feel compelled to choose food B, a less healthier, yet more immediately satisfying choice. The degree to which one gives in to temptation is partly due to an understanding of one's good vs. bad habits (self-knowledge).

Now, this second aspect of consciousness - self-knowledge - is tricky. It is very difficult to disentangle to what extent one's conscious perception is based on prior habits, and how much it is being directly influenced by environmental factors. We all struggle at times to eat healthy. Yet after a long, stressful day at work, the struggle becomes much more difficult. This is especially true when one feels as though the unhealthy yet highly-craved choice is felt to be a sort of reward, as in, "My day was so hard - I deserve this." In this sense, the choice becomes rationalized as a form of justice. It isn't hard to imagine that the more one feels that their lot in life is unjust, that giving in to poor choices can seem justified.

I'm reminded of an incredibly interesting study done on the behavior of rats and their seeming sense of justice and motivation. Unfortunately, I've searched in vain for a link. But from memory, apparently it was found that when rats were placed within viewing distance of other rats, their motivation decreased significantly when they observed inequity in reward. Other research in non-humans has found similar evidence: inequity and unfairness tends to create anger and resentment. It makes sense that this would at the very least create stress. And there is much evidence that stress leads to compensatory, pleasure-inducing mechanisms of self-stimulation to recapture dopamine. When all else fails, eat a candy bar.

This is a Marxist analysis, so it is only appropriate to paraphrase Marx in asking whether low-nutrition, high-pleasure foods are the opiates of the masses.

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

An Ugly Marriage

|

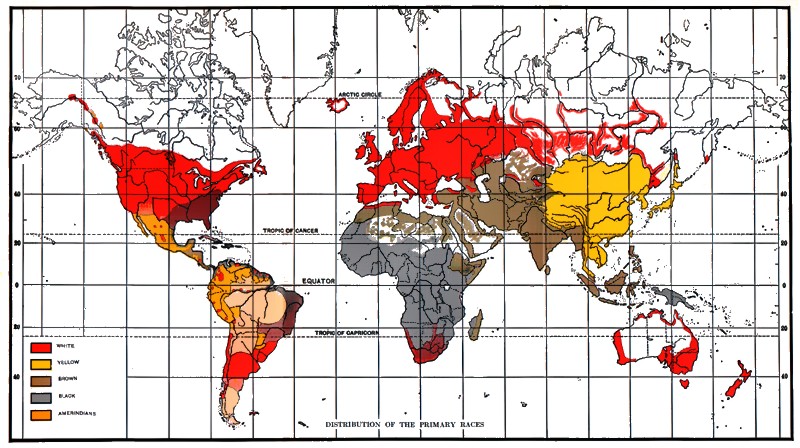

| "Race Map" from 1920 |

My interest piqued by the title, I was struck however by this bit from the synopsis on Amazon,

"Weissberg argues that most of America's educational woes would vanishI then noticed that this was followed by a favorable blurb from none other than John Derbyshire, the conservative columnist for the National Review who was recently fired after achieving infamy in a column in which he pretended (?) to give advice to his white child on how to avoid various threats black people might pose - a racist version of "the talk", the much publicized response amid furor over the George Zimmerman profiling case many black parents have felt necessary giving their children. Here's a little taste:

if indifferent, troublesome students were permitted to leave when they

had absorbed as much as they could learn; they would quickly be replaced

by learning-hungry students, including many new immigrants from other

countries."

...Thus, while always attentive to the particular qualities of individuals, on the many occasions where you have nothing to guide you but knowledge of those mean differences, use statistical common sense:In my last podcast, I pointed to the fact that racists always seem to be conservative. I argued that this is likely due at least in part to the substantive claims conservatism makes. While its logic does not unavoidably lead to racism, its underlying assumptions do much of the logical heavy-lifting. Taking a spin around the site that hosted Derbyshire's writing, the racism is as close to explicit as it gets. And the list of contributors is paleo-conservative to the bone. You can almost hear the brandy glasses clinking in the background as the phrenology calipers are adjusted.

(10a) Avoid concentrations of blacks not all known to you personally.

(10b) Stay out of heavily black neighborhoods.

(10c) If planning a trip to a beach or amusement park at some date, find out whether it is likely to be swamped with blacks on that date (neglect of that one got me the closest I have ever gotten to death by gunshot)....

(11) The mean intelligence of blacks is much lower than for whites. The least intelligent ten percent of whites have IQs below 81; forty percent of blacks have IQs that low. Only one black in six is more intelligent than the average white; five whites out of six are more intelligent than the average black. These differences show in every test of general cognitive ability that anyone, of any race or nationality, has yet been able to devise. They are reflected in countless everyday situations. “Life is an IQ test.”

One might dismiss these radical types as not representative of any larger conservative movement. And to an extent that is no doubt true. Yet while most prominent conservatives would have a hard time coming right out so bluntly, it isn't hard to see how such thinking represents a mere coherence of the nebulous, uncomfortability conservatism has with race and class in general. In a tragic way, race acts as a kind of litmus test for the poisoned waters of "meritocracy", the sly fantasy the right-wing embraces as a means of perpetuating traditional power structures. In a sea of undifferentiated masses, it is easier to pretend that the poor are merely choosing their own sorry destitution. Yet when poverty remains so wedded to race and ethnicity, it becomes hard not to seek explanations either in social structures or genetics. As embracing radical change in social hierarchies is anathema to conservatism, radical paleo-conservatives are merely being honest when they voice their preference to adopt genetic explanations.

Milton Friedman, in his 1980 miniseries Free to Choose

I'm fascinated by the politics of education reform, and the lenses that it gets viewed through. I do agree that the problem is the students, and demographics - you can't argue with facts. But where I differ is that I see this not as a problem of racial or ethnic inferiority, but as one perpetuated by our economic and social system, where human and societal capital are distributed according to privilege.

I see current reform efforts ultimately as a clever alliance between this kind of paleo-conservative racial & class exclusion and neo-liberal naivete that wants to believe that poor kids' only enemy is bad teaching. Vouchers have been replaced by charter schools, which promise to give both groups what they think they want.

Unfortunately, the problem - for those of us neither right-wing racialists, nor pie-in-the-sky teacher demagogues - is about equality of opportunity. If we really want to give kids an equal education, we need to invest in levels of service appropriate to the necessary intervention. That, we have not yet begun.

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

But What Kind of Collaboration?

A recent article in the Atlantic emphasizes the need for more collaboration among teachers in schools.

Saturday, April 14, 2012

A Difference in Framing

Non-reformer writes: "Because we know that poorly educated parents and poverty are the root causes of poor achievement."

Reformer responds: "We don't know that at all. In fact, all historical and global evidence would completely contradict that hypothesis. What we know is that poor children in the U.S. are not educated well within the U.S. public education system."

Curiously, if one could sum up the education Reform mindset, it might come down to this difference in framing. Reformers tend to want to diminish the effects of SES, and emphasize teacher efficacy. The response from Non-reformers is generally to push back and emphasize SES. The Reformer often calls this "making excuses", famously "the soft bigotry of low expectations". The term reform itself has become loaded as it sets up one particular framework as being reform, and anything else as, well, non-reform. And when everyone agrees the education system is broken, the non-reformer becomes defined by an implication that they support the system as it stands.

Non-reformer responds: "Of course it is not poverty itself that affects learning but the EFFECTS of poverty ...."

However, most Non-reformers I know (which also happens to be most teachers and non-teachers), actually want even greater reforms to education. They don't see teachers as the problem, but larger social problems. They point to all the things the Non-refomer referred to - the EFFECTS - of poverty as being what we need to reform.

Now, part of the difference in frameworks might have to do with a broader sort of political temperament. Reformers have been so successful because they have built a coalition of conservatives and neo-liberals. As a group, a common feature is a tendency away from radical, progressivism. Yet this is exactly what non-reformers would champion.

The reality is of course, that the public is in no mood for radical progressivism. There is simply no political momentum toward an agenda of going after the EFFECTS (as Linda so succinctly put it) of poverty, which would require massive (OK, *cough* I use this term relatively! "Imagine if they had to have a bake sale...") state spending.

So the neo-liberal model, biased as it is towards the political *possible*, essentially has thrown in the towel on looking at SES as the real reform and emphasizing instead the marginal benefits of squeezing more achievement out of teachers. Unfortunately, the result has been so good. I realize my bias as a non-reformer, but there just doesn't seem to be much evidence that union-busting, charters, performance-pay, punitive testing, etc. has really done much at all.

Non-reformers would say, of course, "See. I told you so." And the system has been really screwed up. Teachers feel completely demoralized, their jobs as un-meaningful as ever, expectations higher than ever yet their tasks only more daunting, humanity removed from the profession and countless punitive professional development sessions and administrators forced by their bosses into a bizarro world that fundamentally misunderstands the classroom.

Personally, I think all this "reform", based as much of it has been on an attempt to find consensus and work within political realities has not only made the system worse, but has moved the debate away from where it really should be. To use an analogy, it would be as a bus were speeding towards you and instead of jumping out of the way, you start running in the opposite direction, hoping it won't catch up. Well, I think it's finally caught up.

Reformers talk about making "excuses". However, I would argue it is they who are the real excuse-makers. By constantly shifting the blame away from larger, more serious social problems, they excuse them. The reality is that the achievement gap is based on a fundamental reality: SES means human and societal capital. The advantaged have a lot more of it than the disadvantaged. Reformers would have us believe that this inequality can be overcome simply by "better teaching". They would have us believe that teachers in a poor community should be expected to work twice as hard - be twice as good - as teachers in affluent communities.

Yet in the end, what this tells poor communities is that, despite your lower levels of human and societal capital, we're not going to give you any more support. We're going to force to to rely on the same teaching pool as everyone else, even though your needs are so much more profound. Imagine if we did this with police departments. What if every neighborhood only got a limited number of service calls, then we blamed the police for the rise in crime rates?

That isn't reform. It's perpetuation of social inequality by a privileged class who doesn't want to sacrifice for those less fortunate. It's also a betrayal of what public education has always been about.

Monday, April 9, 2012

A Model for True Reform

(cross-posted from Solutions for Educators)

As this is my first guest post here at Solutions for Schools, let me start by introducing myself. I currently teach science at a continuation high school, but I also have experience teaching kindergarten, as well as a number of years spent as a substitute in a number of districts around the country. Before I was a teacher, I worked in various areas of social services. I have a profound commitment to social justice and equality of opportunity for all citizens. I originally went into education because I felt that it was where I could do the most good in this regard. Unfortunately, the reality of what I have seen has disabused me of much of my former naivete. In community after community, I have seen a severity of developmental problems being dealt with heroically by local schools. Yet under-resourced and trapped in larger policy framework that fails to grasp the reality of the situation, they cannot help but fail in their mission of closing the achievement gap and guaranteeing every child an equal education.

Where I teach, the students are basically the "worst of the worst", in terms of academic, behavioral and emotional problems. Primarily juniors and seniors, their profiles are colored by severe truancy, substance abuse, mental illness (mainly depression), defiance and poor impulse control, broken homes, teen pregnancy and poor academic skills. They are incredibly diverse in life experience, with common denominators generally being poverty and low-parent income and education. At this point in their education, they are more in need of triage than anything else. Because they are credit deficient, and so fragile emotionally and behaviorally, they are given condensed curriculum packets that they can quickly finish and move on from. Even this however, proves too much for many of them too handle, and many disappear to never return, or spend days, weeks - even months - staring at their (admittedly) boring work and never completing any of it. Direct instruction is, as you might imagine, neither effective nor practical with this population. (As a non-tenured teacher, I was actually recently asked not to return by an administrator who insisted on direct instruction and was thus penalized when my students failed to be "properly engaged". There was likely an element of caprice involved as well, but suffice it to say that what I was doing was no different than any other teacher in the building, who all agreed that direct instruction was inappropriate, and whose students displayed equal levels of disengagement.)

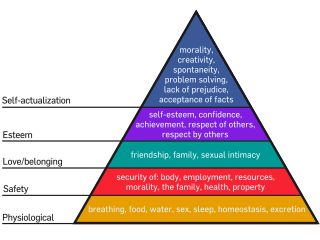

So, let us now look at why these students are so difficult to engage. Two ideas in education have powerful explanatory power here: Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs and Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development. The former essentially states that there is a hierarchy of human needs, and that lower levels must be satisfied before higher levels can be achieved. For instance, a lower level need like hunger will have a profoundly negative effect on higher order needs such as the acquisition of critical thinking or moral integrity. Vygotsky’s theory refers to “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, 1978). This concept is of central importance to foundational pedagogical ideas such as differentiation, scaffolding, and constructivism.

Since Maslow's writing half a century ago, there has been considerable

support for his theory, especially in brain sciences. The areas of the

brain responsible for higher-order thinking and complex problem-solving are

secondary to the more primitive areas of the brain which are responsible for

regulating basic physiological processes. An example of this we can all

relate to would be to try to imagine studying for a test while a jackhammer is

blasting just outside the window. A more psychodynamic extension of this

problem would be not a jackhammer but a negative emotional state plaguing the

conscious mind with disruptive ideations. The primitive brain is thus

being constantly stimulated, and essentially re-routing brain power towards the

regulation of first-order needs. As we age and develop, we hopefully

acquire compensatory skills that allow us to better regulate primitive brain

responses. But there will still always be a limit to our regulatory

capacity. This is especially true for children, especially children

coming from environments of profound neglect, or ones that actively contribute

to negative stimulus response - for example, an angry, stressed-out parent or daily

peer bullying.

In my classroom, students exist in the lower levels of the needs hierarchy. Many of their affective behaviors can be seen as natural defense mechanisms, primarily the direct result of not having these needs met, and natural response mechanisms. Students are actually highly aware of this, routinely speaking of being stressed out. Unfortunately, their go-to responses tend to be highly dysfunctional: substance abuse, fighting, crime, or sex. That so much of the music they listen to is essentially a glorification of these unhealthy responses is indicative of a wider pattern throughout their communities. Many students, also, will speak openly of behaviors among family and friends - often adults - that are clearly unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Of course, these behaviors are considered unhealthy because of the detrimental effect they have both personally and in the community. It is therefore unsurprising that what goes on in the community will also go on in the classroom. With my students, this is literally true as fights break out with relative frequency, and students routinely come to school high or intoxicated. The janitor sometimes shows me the empty beer cans he retrieves from the bathroom. One student - a mother of a 2 year old - once came to my class late, reeking of alcohol. I let her in, and handed her the worksheet we were using with a video. During the lesson, she blurted out, "Mr. Rector, hurry up! I'm falling asleep!" Indeed, she passed out at her desk shortly thereafter.

Of course, I could have sent her to the office so that she could be suspended on suspicion. However this is something I rarely do, even when I have reason to suspect drug abuse is occurring. My reasoning is that there would be little point. Students are suspended right and left, and what this mainly means is that they get a short holiday from school. Remember, these students have records a mile long. The parents have long since lost control of them - and in many cases actively contribute to their dysfunction. No, I generally believe that my classroom is a "safe harbor". I would rather they be with me, safe, then anywhere else. I talk to them about their issues. I listen to their concerns and do my best to guide them to appropriate behavior. Punishing them often has the effect of building up their defensive walls, instead allowing them to come down so that healing can begin. Rebuilding trust is a critical step in the process of reintegration with positive social norms - as opposed to the negative norms of their peer group, or frequently that of their family. Evidence of the efficacy of this approach I believe has earned me the honor of one of the "best-loved" teachers in the school, and students routinely open up to me with their problems and concerns. What follows from this process of emotional growth is both an increased academic as well as behavioral classroom engagement.

This need for affirmation and rebuilding of trust is, I feel, the student's primary need. After speaking with the counselors, it became clear to me that if I wasn't going to do it, then no one would. The counselors had their hands full on procedural, academic matters, and never had the time to build the kind of student relationships required. A grant was once written for a psychological counselor, but therapy limited to one hour a week was impractical for a variety of reasons, the most salient being that rapport was still difficult to establish, and truancy was often an issue for the students in greatest need of help. As a teacher, I see the students one or two hours a day, and am able to build up enormous levels of trust and rapport. This can only happen in a non-direct instruction setting, when there is the time and environment conducive for casual discussion. A common technique of mine is to enter into a discussion between a group of students - non-schoolwork related, of course! - and through humor or genuine interest insinuate myself in the conversation. After a certain point in the year, the students actually actively welcome my insights. I tend to tell colorful stories, or try in some other way to creatively engage them so as to both respect their experiences and attitudes, but also to subtly guide them to more healthy modes of thought and behavior. In a way, it is a sort of psychological jujitsu - using their - often negative - thoughts and experiences to expose them to a more positive world.

I admit this is highly unconventional, and not something one could easily be trained in, or even really explain to someone who would not at least grasp it in some intuitive way. The technique doesn't always work, and my mistakes often haunt me. For instance, coming on too strong can risk a defensive reaction and dismissal as an outsider undeserving of trust. With such a fragile population, this can be disastrous. Many students will literally only come to school for the sake of one or another teacher who they feel a connection with. Breaking a fragile bond can literally mean the difference between dropping out and coming to school, or even something more serious, such as getting too high at a party or behaving too recklessly. I've seen too many students be pulled away from the brink by the love they receive from school staff to question its centrality to their lives. It also helps that I possess a relatively intimate knowledge of their culture. When students learn that I have my own rap album their jaws drop in disbelief! (Unfortunately, because of the explicit nature of some of the lyrics I only play them short snippets - which likely only increases the mystique).

So, how does any of this relate to academics? Do the students ever actually learn anything, or do they merely sit around and goof-off all day? Not if I have anything to say about it. Because of the instructional limitations I referred to previously, I have had to be very creative in developing from scratch a curriculum that is generalizable to a broad range of academic skill levels, is something that students will actually attempt to complete and not be put off by (a serious problem for many), is aligned with the standards, encourages higher-order thinking, and hopefully doesn't bore them to tears. At any given moment in a classroom, I will have students working in any area of any one of 4 quarters of either Biology or Earth Science. I spend my days facilitating their movement through the material, taking pre and post assessments, designing projects, and generally trying to keep them on-task, supplied with paper and pencils, etc. Many of them will still refuse to do much work. But it is my job to teach them, and every day I do my best to come up with ways of reaching them. Ultimately, even if they aren't going to leave my classroom knowing the difference between convection and radiation, or the process of protein synthesis, at least they will have experienced my love and support, and my unconditional belief in them. And in the end, this will no doubt help them more when dealing with the boss in a crappy service-wage position or - sad to say - pimp or prison guard.

Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal development tells us that learning is self-building, or, that new knowledge can only be integrated with the old. This is generally thought of in education in terms of academic development. A student with a reading level of 3 should not be reading a book at level 13. It would make much more sense to have them read a range of levels, say 1-6, the lower levels for confidence, the higher levels for skill building. As such, teachers must differentiate their instruction so as to target optimal levels of development and content integration. This is always a difficult task, and made more so in disadvantaged communities, where the developmental range in any one classroom can be vast.

But apart from academic skill, this model can be applied to different developmental domains. Students diverge widely in skill such as cognitive processing (something like the ability to organize ideas, or contrast new ideas with the old), or emotional regulation (taking time to breath before responding to an insult), or cultural and behavioral norms. We know from Hart andRisley that low-income children tend to come to school with vastly lower vocabularies. But an often overlooked aspect to their landmark study is the nuance in parenting styles accompanying that language gap, and the degree to which cognition is stimulated at home. For instance, in one home, a toddler who picks up an object and brings it to the mother might hear something like, "Be careful. Put that back. That isn't yours." While in another household, the child might hear something like, "What is that you have? Oh, it’s a stapler. Mommy uses that for papers. Yes, it's heavy. Let's put it back where it goes. Where is your ball?" These two responses represent not merely different parenting styles, but different levels of the kinds of environmental stimulus that build dynamic neural pathways. These compound for years and years, over thousands of hours, leading to widely divergent developmental skill-sets. Annette Lareau wrote powerfully of this in her book Unequal Childhoods.

Public schools in America have never been properly designed to handle such differing needs among a diverse public. For a number of larger socio-economic reasons, there exist profound developmental disparities across classes, and concentrated into different neighborhoods. The traditional model of one teacher and one classroom of 25-35 students drawn from the local community largely at random has been disastrous. Current attempts at reform have done little to address the underlying problem of development and differentiation. Excuses and exceptions have been found in an attempt to promote the notion that this model is sustainable. They have largely centered around the notion that individual teachers have simply not been doing a good enough job.

Yet this doesn't explain the overwhelming pattern of failure in poor schools, as the relative efficacy of teachers has been shown to be rather evenly distributed across affluent and poor schools alike. It is certainly the case that a less-effective teacher is going to do more harm at a poor school than she would at an affluent school. This would be true of any occupation. It is just as true that an effective teacher is going to be less effective at a school in which the student population is developmentally disadvantaged. Pretending that the solution is to find all the best teachers and send them to all the poor schools is not only highly unrealistic, but a bizarre way of looking at the problem. It would be as if our solution to a troubled war zone was not to invest in more resources or different tactics, but to blame ordinary troops and instead send in super-soldiers. I call this the "Rambo Escalante" model, based as it is on part fantasy, part misunderstanding of child development and the constraints of the current classroom model.

What then, would I propose in place of current reform models ultimately built around the notion that bad teaching is the problem, such as pay-for-performance, union busting charters, testing accountability and endless professional development? Critics have long assailed calls for more resources as "throwing money at the problem". Yet of course, this ignores the vast amounts of money NCLB has spent in pursuit of its goals. I'm not sure how much money my ideas might cost, but they will no doubt be expensive. If effective, however, they will pay for themselves many times over in increased productivity and reduced secondary social costs.

Some of what I think needs to happen is being implemented in small ways in different parts of the country, as individual programs are run in isolation. Yet it is rarely the case that a comprehensive system is established that truly intervenes in the developmental problem in a targeted, long-term way. The student I spoke of earlier, drunk in class with a two year old at home? What can be done for that two year old child right now, and for the next 16 years so that she will graduate with an equal chance of success in life, as a citizen with relatively equal prospects? Social services and educational institutions need to essentially close ranks, and envelop the child in a rich network of inter-connected, orchestrated outreach that assess and target her environmental needs so as to provide agile interventions both for her as well as her family. Her mother no doubt already has substance abuse issues. There are likely negative interactions with law enforcement among friends and family. The state is already no doubt intervening in their lives. I would propose however, the interventions - while conducive to the short-term safety of the rest of society - they are not conducive to the building of human and societal capital in that family cohort, and in many ways may be depleting it.

I don't know what a well-designed ecosystem of social services would look like. But I know what its functional purpose would be. And that, I fear, is more than can be said for too many of would-be education reformers today.

As this is my first guest post here at Solutions for Schools, let me start by introducing myself. I currently teach science at a continuation high school, but I also have experience teaching kindergarten, as well as a number of years spent as a substitute in a number of districts around the country. Before I was a teacher, I worked in various areas of social services. I have a profound commitment to social justice and equality of opportunity for all citizens. I originally went into education because I felt that it was where I could do the most good in this regard. Unfortunately, the reality of what I have seen has disabused me of much of my former naivete. In community after community, I have seen a severity of developmental problems being dealt with heroically by local schools. Yet under-resourced and trapped in larger policy framework that fails to grasp the reality of the situation, they cannot help but fail in their mission of closing the achievement gap and guaranteeing every child an equal education.

Where I teach, the students are basically the "worst of the worst", in terms of academic, behavioral and emotional problems. Primarily juniors and seniors, their profiles are colored by severe truancy, substance abuse, mental illness (mainly depression), defiance and poor impulse control, broken homes, teen pregnancy and poor academic skills. They are incredibly diverse in life experience, with common denominators generally being poverty and low-parent income and education. At this point in their education, they are more in need of triage than anything else. Because they are credit deficient, and so fragile emotionally and behaviorally, they are given condensed curriculum packets that they can quickly finish and move on from. Even this however, proves too much for many of them too handle, and many disappear to never return, or spend days, weeks - even months - staring at their (admittedly) boring work and never completing any of it. Direct instruction is, as you might imagine, neither effective nor practical with this population. (As a non-tenured teacher, I was actually recently asked not to return by an administrator who insisted on direct instruction and was thus penalized when my students failed to be "properly engaged". There was likely an element of caprice involved as well, but suffice it to say that what I was doing was no different than any other teacher in the building, who all agreed that direct instruction was inappropriate, and whose students displayed equal levels of disengagement.)

So, let us now look at why these students are so difficult to engage. Two ideas in education have powerful explanatory power here: Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs and Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development. The former essentially states that there is a hierarchy of human needs, and that lower levels must be satisfied before higher levels can be achieved. For instance, a lower level need like hunger will have a profoundly negative effect on higher order needs such as the acquisition of critical thinking or moral integrity. Vygotsky’s theory refers to “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, 1978). This concept is of central importance to foundational pedagogical ideas such as differentiation, scaffolding, and constructivism.

|

| Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Pyramid |

In my classroom, students exist in the lower levels of the needs hierarchy. Many of their affective behaviors can be seen as natural defense mechanisms, primarily the direct result of not having these needs met, and natural response mechanisms. Students are actually highly aware of this, routinely speaking of being stressed out. Unfortunately, their go-to responses tend to be highly dysfunctional: substance abuse, fighting, crime, or sex. That so much of the music they listen to is essentially a glorification of these unhealthy responses is indicative of a wider pattern throughout their communities. Many students, also, will speak openly of behaviors among family and friends - often adults - that are clearly unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Of course, these behaviors are considered unhealthy because of the detrimental effect they have both personally and in the community. It is therefore unsurprising that what goes on in the community will also go on in the classroom. With my students, this is literally true as fights break out with relative frequency, and students routinely come to school high or intoxicated. The janitor sometimes shows me the empty beer cans he retrieves from the bathroom. One student - a mother of a 2 year old - once came to my class late, reeking of alcohol. I let her in, and handed her the worksheet we were using with a video. During the lesson, she blurted out, "Mr. Rector, hurry up! I'm falling asleep!" Indeed, she passed out at her desk shortly thereafter.

Of course, I could have sent her to the office so that she could be suspended on suspicion. However this is something I rarely do, even when I have reason to suspect drug abuse is occurring. My reasoning is that there would be little point. Students are suspended right and left, and what this mainly means is that they get a short holiday from school. Remember, these students have records a mile long. The parents have long since lost control of them - and in many cases actively contribute to their dysfunction. No, I generally believe that my classroom is a "safe harbor". I would rather they be with me, safe, then anywhere else. I talk to them about their issues. I listen to their concerns and do my best to guide them to appropriate behavior. Punishing them often has the effect of building up their defensive walls, instead allowing them to come down so that healing can begin. Rebuilding trust is a critical step in the process of reintegration with positive social norms - as opposed to the negative norms of their peer group, or frequently that of their family. Evidence of the efficacy of this approach I believe has earned me the honor of one of the "best-loved" teachers in the school, and students routinely open up to me with their problems and concerns. What follows from this process of emotional growth is both an increased academic as well as behavioral classroom engagement.

This need for affirmation and rebuilding of trust is, I feel, the student's primary need. After speaking with the counselors, it became clear to me that if I wasn't going to do it, then no one would. The counselors had their hands full on procedural, academic matters, and never had the time to build the kind of student relationships required. A grant was once written for a psychological counselor, but therapy limited to one hour a week was impractical for a variety of reasons, the most salient being that rapport was still difficult to establish, and truancy was often an issue for the students in greatest need of help. As a teacher, I see the students one or two hours a day, and am able to build up enormous levels of trust and rapport. This can only happen in a non-direct instruction setting, when there is the time and environment conducive for casual discussion. A common technique of mine is to enter into a discussion between a group of students - non-schoolwork related, of course! - and through humor or genuine interest insinuate myself in the conversation. After a certain point in the year, the students actually actively welcome my insights. I tend to tell colorful stories, or try in some other way to creatively engage them so as to both respect their experiences and attitudes, but also to subtly guide them to more healthy modes of thought and behavior. In a way, it is a sort of psychological jujitsu - using their - often negative - thoughts and experiences to expose them to a more positive world.

I admit this is highly unconventional, and not something one could easily be trained in, or even really explain to someone who would not at least grasp it in some intuitive way. The technique doesn't always work, and my mistakes often haunt me. For instance, coming on too strong can risk a defensive reaction and dismissal as an outsider undeserving of trust. With such a fragile population, this can be disastrous. Many students will literally only come to school for the sake of one or another teacher who they feel a connection with. Breaking a fragile bond can literally mean the difference between dropping out and coming to school, or even something more serious, such as getting too high at a party or behaving too recklessly. I've seen too many students be pulled away from the brink by the love they receive from school staff to question its centrality to their lives. It also helps that I possess a relatively intimate knowledge of their culture. When students learn that I have my own rap album their jaws drop in disbelief! (Unfortunately, because of the explicit nature of some of the lyrics I only play them short snippets - which likely only increases the mystique).

So, how does any of this relate to academics? Do the students ever actually learn anything, or do they merely sit around and goof-off all day? Not if I have anything to say about it. Because of the instructional limitations I referred to previously, I have had to be very creative in developing from scratch a curriculum that is generalizable to a broad range of academic skill levels, is something that students will actually attempt to complete and not be put off by (a serious problem for many), is aligned with the standards, encourages higher-order thinking, and hopefully doesn't bore them to tears. At any given moment in a classroom, I will have students working in any area of any one of 4 quarters of either Biology or Earth Science. I spend my days facilitating their movement through the material, taking pre and post assessments, designing projects, and generally trying to keep them on-task, supplied with paper and pencils, etc. Many of them will still refuse to do much work. But it is my job to teach them, and every day I do my best to come up with ways of reaching them. Ultimately, even if they aren't going to leave my classroom knowing the difference between convection and radiation, or the process of protein synthesis, at least they will have experienced my love and support, and my unconditional belief in them. And in the end, this will no doubt help them more when dealing with the boss in a crappy service-wage position or - sad to say - pimp or prison guard.

Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal development tells us that learning is self-building, or, that new knowledge can only be integrated with the old. This is generally thought of in education in terms of academic development. A student with a reading level of 3 should not be reading a book at level 13. It would make much more sense to have them read a range of levels, say 1-6, the lower levels for confidence, the higher levels for skill building. As such, teachers must differentiate their instruction so as to target optimal levels of development and content integration. This is always a difficult task, and made more so in disadvantaged communities, where the developmental range in any one classroom can be vast.

But apart from academic skill, this model can be applied to different developmental domains. Students diverge widely in skill such as cognitive processing (something like the ability to organize ideas, or contrast new ideas with the old), or emotional regulation (taking time to breath before responding to an insult), or cultural and behavioral norms. We know from Hart andRisley that low-income children tend to come to school with vastly lower vocabularies. But an often overlooked aspect to their landmark study is the nuance in parenting styles accompanying that language gap, and the degree to which cognition is stimulated at home. For instance, in one home, a toddler who picks up an object and brings it to the mother might hear something like, "Be careful. Put that back. That isn't yours." While in another household, the child might hear something like, "What is that you have? Oh, it’s a stapler. Mommy uses that for papers. Yes, it's heavy. Let's put it back where it goes. Where is your ball?" These two responses represent not merely different parenting styles, but different levels of the kinds of environmental stimulus that build dynamic neural pathways. These compound for years and years, over thousands of hours, leading to widely divergent developmental skill-sets. Annette Lareau wrote powerfully of this in her book Unequal Childhoods.

Public schools in America have never been properly designed to handle such differing needs among a diverse public. For a number of larger socio-economic reasons, there exist profound developmental disparities across classes, and concentrated into different neighborhoods. The traditional model of one teacher and one classroom of 25-35 students drawn from the local community largely at random has been disastrous. Current attempts at reform have done little to address the underlying problem of development and differentiation. Excuses and exceptions have been found in an attempt to promote the notion that this model is sustainable. They have largely centered around the notion that individual teachers have simply not been doing a good enough job.

Yet this doesn't explain the overwhelming pattern of failure in poor schools, as the relative efficacy of teachers has been shown to be rather evenly distributed across affluent and poor schools alike. It is certainly the case that a less-effective teacher is going to do more harm at a poor school than she would at an affluent school. This would be true of any occupation. It is just as true that an effective teacher is going to be less effective at a school in which the student population is developmentally disadvantaged. Pretending that the solution is to find all the best teachers and send them to all the poor schools is not only highly unrealistic, but a bizarre way of looking at the problem. It would be as if our solution to a troubled war zone was not to invest in more resources or different tactics, but to blame ordinary troops and instead send in super-soldiers. I call this the "Rambo Escalante" model, based as it is on part fantasy, part misunderstanding of child development and the constraints of the current classroom model.

What then, would I propose in place of current reform models ultimately built around the notion that bad teaching is the problem, such as pay-for-performance, union busting charters, testing accountability and endless professional development? Critics have long assailed calls for more resources as "throwing money at the problem". Yet of course, this ignores the vast amounts of money NCLB has spent in pursuit of its goals. I'm not sure how much money my ideas might cost, but they will no doubt be expensive. If effective, however, they will pay for themselves many times over in increased productivity and reduced secondary social costs.

Some of what I think needs to happen is being implemented in small ways in different parts of the country, as individual programs are run in isolation. Yet it is rarely the case that a comprehensive system is established that truly intervenes in the developmental problem in a targeted, long-term way. The student I spoke of earlier, drunk in class with a two year old at home? What can be done for that two year old child right now, and for the next 16 years so that she will graduate with an equal chance of success in life, as a citizen with relatively equal prospects? Social services and educational institutions need to essentially close ranks, and envelop the child in a rich network of inter-connected, orchestrated outreach that assess and target her environmental needs so as to provide agile interventions both for her as well as her family. Her mother no doubt already has substance abuse issues. There are likely negative interactions with law enforcement among friends and family. The state is already no doubt intervening in their lives. I would propose however, the interventions - while conducive to the short-term safety of the rest of society - they are not conducive to the building of human and societal capital in that family cohort, and in many ways may be depleting it.

I don't know what a well-designed ecosystem of social services would look like. But I know what its functional purpose would be. And that, I fear, is more than can be said for too many of would-be education reformers today.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

Self-Destruction as Rebellion

|

| image: Paulina Sergeeva |

In a guest piece on teen pregnancy for edweek, he writes about a student's life who is completely derailed by an unplanned pregnancy.

Most unfortunate is that this student had the potential to transform his life's path from one of poverty to one of hope and prosperity. The American Dream was within grasp. His future options used to be between universities. He is now choosing between a superstore and a fast-food joint, as his only concern is supporting his child, "being a father better than the one I never knew."

This is an enormous problem, and a major contributor to generational poverty. In my career, I've taught both Kindergarten in a poor community, as well as continuation high school students. So, I've seen the sort of cycle of underdevelopment that runs through the system.

In my kindergarten class, I saw first hand what is born out in the research: most of my students were coming in with almost zero knowledge of the alphabet or numeracy. Cognitive skills were quite low, and there were a number of behavioral problems.

With "at-risk" high-schoolers, it is not uncommon to see low-elementary reading levels. You ask yourself, "How did they get this far without learning to read or do basic multiplication?" But it isn't so simple. Many had moved multiple times, or had terrible truancy issues. But more common, I think, was this weird sort of "immunity to learning". You could maybe get them to take notes, work with them one-on-one to flesh out concepts, and it might stick for a time, but it would then disappear.

What I think is going on is that such students are in a state of severe rebellion against learning. A process of disassociation happens whereby they go through the motions, but at a deep level resent the whole system and gain control by refusing to learn.

I actually see pregnancy as a symptom of a similar attitude of rebellion. For the boys, having sex and being tough is a badge of honor. (The glorification of fighting is immense - they practice with each other and routinely brag about it). It is a continuous "F*** You" to the system. For the girls, not having sex, but actually getting pregnant seems to serve a similar purpose. They see no future for themselves, and when faced with what seem like impossible life expectations, having a baby is the ultimate act of defiance.

These students have been told all their lives to do the "right thing", and they haven't been able to, because they have never been able to develop the emotional, behavioral and cognitive skills to do so. In crowded classrooms, with overburdened teachers and a community that is failing all around them, they've fallen further and further behind.

And yet the societal scolding remains: you can't do the work, you can't behave, you can't follow rules, you and your culture are worthless. They see this implied not only to them, but to their community in general. And so they rebel. And the ultimate rebellion is self-destruction. It is the attitude of, "If this is what you think of me, I'll show just how bad I can be!"

Now, I think it is likely rare that they hear this message explicitly. Most social workers and teachers I have worked with have been very supporting and loving. Yet the sum of the effects of the response to their behavior amounts to an implicit judgement of them as inferior human beings.

There is an important point here that needs to be made. We, as a society, still fail to integrate what we know about human development with our social response. At one level, we understand that there are reasons for why people do what they do. But when it comes to our response, we struggle to incorporate that understanding.

For example, a student who misbehaves is often scolded for having made "wrong choices". Now, he did make bad choices. But he only made them because he hadn't developed the capacity to not make them. This is why we have so much compassion and understanding for small children. Yet as they age, we become less and less understanding. Eventually, we completely give up. We assume them to be in complete control of their actions and able to have made the "right decision". Yet this is clearly not true! While as people age and their developmental process becomes much more complex and hard to track, it is not fundamentally different than that of a small child. There are still reasons for why they were or were not able to make decisions.

Our failure in education has been, I feel, rooted in our failure as a society to understand human development. We have not made the connection between development and consciousness, development and behavior. If we are to truly solve teen pregnancy, we are going to have to solve deeper problems of human agency.

A good place to start will be to begin to do better, earlier assessments of children. These will point us towards the kinds of targeted interventions that will allow us to deliver high-resolution developmental remediation where it is needed.

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Moneyroom

Last night I made the mistake of watching the film Moneyball, about the baseball general manager Billy Beane, played by Brad Pitt, who figured out a way to revolutionize his sport by concentrating solely on his players' statistical performance, as opposed to the inclusion of more traditional measures such as personality, looks, attitude, health, age or other difficult-to-quantify factors. The underdog element of the story gives it its biggest punch, as the team he manages resides in a smaller market, and thus can't afford to compete with larger teams, who can afford to buy superstars for their teams.

Yet this appeal to humility makes the film deeply ironic. A sense of unfairness and cold economics is responded to with an even colder, albeit deviously smart, emphasis on calculation and dehumanization. While romantic notions of well-matched competition might have been dashed by market realities and multi-million-dollar salaries that turned the game into a dueling of paychecks, the underdog response is neither pluck, serendipity nor sheer human courage, but rather a double-down dueling of rigid statistical maneuvering. Adding insult to injury, the team is managed like widgets, coldly fired and hired at will, shuffled like inorganic set-pieces. Tellingly, the film seems to recognize this dynamic, and in a nod to the existence of what a more touchy-feely type might describe as human "spirit", draws a causal connection between more humane contact between administration and the players and their increased performance on the field.

Whether because I'm not a natural fan of baseball, or just tedious scenes of complex business deals over speaker-phones, I eventually turned the film off in boredom. Maybe I just could look at a cocky Brad Pitt shoving another hotdog into his plump lips, talking about the "bottom line" in his greasy sport shirts.

Or maybe because the story hit too close to home. The film's parallels to education reform are many, even if there are as many differences. The deepest problem in education may indeed be that so many in the reform movement wouldn't see the differences.

Leaving aside the romance of the game, the outcome in sports is perfectly clear: runs, points, errors, touchdowns, etc. All are right there in front of you in black and white. Success means stepping up to the plate and delivering. In education, this is true as far as it goes: a good test score generally means a kid is doing well in school. However, how you get there is infinitely more complex. In baseball, the individual player is largely responsible for his own success or failure. He puts in the training hours, and he ultimately gives it his best on the field.

The education reform movement is nothing if not infatuated with numbers. It designed the infamous NCLB laws that mandated nationwide testing. It tied those scores to classroom teaching. It penalized schools and teachers who didn't improve their students' scores. It brought a business-oriented buzzwords like "accountability", "data" and "performance". It sought to ignore the human side of teaching, what is possibly one of the most complex of human endeavors, reducing everything to the "bottom-line", literally a number in a column.

Yet this reductionist model, while maybe more meaningful in a simple system like professional sports, or a widget factory, required in its pursuit of simplicity and convenience a throwing out, or ignoring, of vast amounts of relevant data. Because while baseball players, or widgets, are relatively static, known quantities, students are not. A baseball player is a highly motivated individual with a set of comprehensive statistics. A widget is an inorganic unit with a weight, size and shape that can be measured with perfect precision.

A classroom on the other hand, is a dynamic group of children, all with complex environmental and developmental needs, from a multiplicity of backgrounds and circumstances that change by the day, that must be differentiated by a teacher. The teacher does not merely deliver content into their heads as if static receptacles. The teacher must first create an environment in which their minds are safe and comfortable enough to become open to positive learning. Their social interaction and participation must be carefully orchestrated so as to facilitate not only the acquisition of new knowledge, but its digestion and synthesis with old knowledge to form

greater and deeper understandings which can then be applied in novel ways. The teacher must assess and identify where each student is at every single moment of class, and subsequently deliver instruction tailored to their specific and unique needs.

In contemporary American society, we are still highly stratified and segregated by human and societal capital. Thus, a given school's demographic population will vary widely from one community to the next. The specific and unique needs of the students in classroom X at school Y will be entirely different than the needs of the students in classroom A in school B. The teaching of such diverse populations of children will be dramatically different. Because the needs of the students are so different, so to will be their capacity to learn. For instance, a student with a vocabulary of 20k words will have a much more difficult time studying a given length of grade-level text than a student with a vocabulary of 40k words. Or, to present a non-academic, but rather environmental, physiological example, a student from a single-parent household who had to put himself to bed, fix his own breakfast, and then ride a bus filled with angry, bullying children will face similar struggles when presented with text to read, when compared with a child from a two-parent home who was lovingly read to before bed, gently woken up, had her hair brushed and driven to school by a calm, soothing mother.

I was recently let-go by a principal who was disappointed that my students were not as engaged as he felt they should have been in my direct-instruction lessons. This, despite the fact that I teach at a continuation school, where the population is severely emotionally and academically underdeveloped, and face all manner of trauma at home. For this reason, the staff rarely bothers with direct-instruction, because it is an ineffective model of instruction with our student population, and for the most part only does so because administrators insist on scoring them according to a direct-instruction rubric. Comments attached to my low-marks would say things like, "a few students were not taking notes", or "one student kept looking at his cell phone".