|

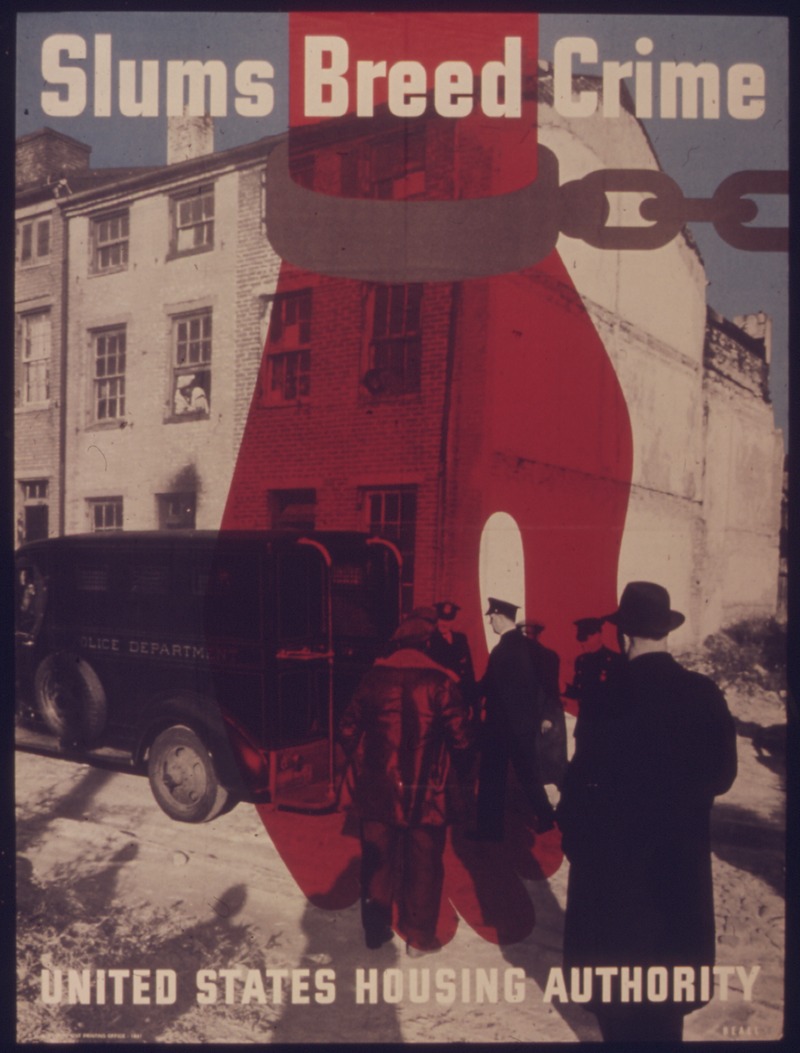

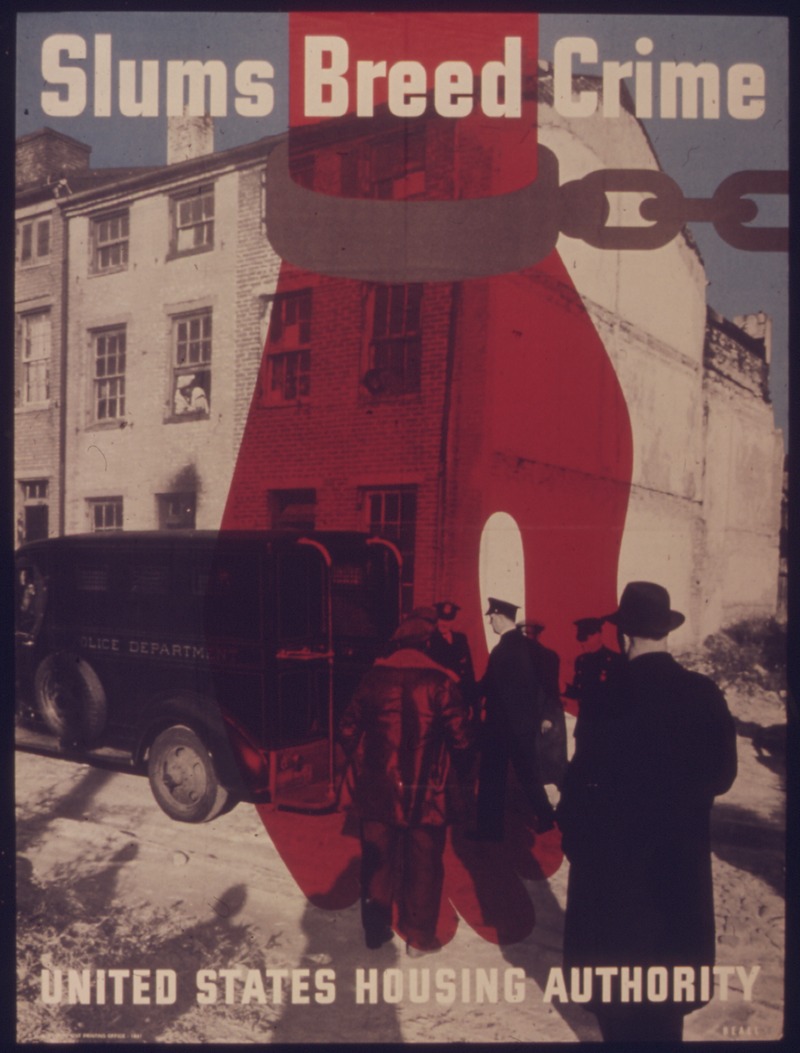

| Unite States Housing Authority poster, 1940 |

Keith Humphreys has an

important piece in the WaPo today highlighting the nuance of poor black communities with regard to violence and incarceration.

In his new book, Locking Up Our Own, Yale University Law School Professor James Forman Jr. points out that in national surveys conducted over the past 40 years, African Americans have consistently described the criminal justice system as too lenient. Even in the 2000s, after a large and sustained drop in the crime rate and hundreds of thousands of African Americans being imprisoned, almost two-thirds of African Americans maintained that courts were “not harsh enough” with criminals.....Through a compelling mixture of personal stories and wonky data analysis, Fortner and Forman document how African Americans have grappled with an anguished choice. On the one hand they want to protect themselves from crime, on the other hand they know that the more active and powerful the criminal justice system grows, the more African Americans will be caught up in it, some of whom will be subjected to grossly racist treatment.

As for Forman's policy recommendations - "expanded employment opportunities, improved housing options and better schools" - I'm not sure how far they will get into the problem. Even if you had all of these things, the black community would still have a lot of difficult contingencies to reckon with.

Education always seems most meaningful to me, as you're getting kids while they're young. But without a solid home, you're going to be spending a ton of money chasing maladaptive behaviors. A lot of the so-called innovation we see in creating "good schools" is really about selectivity, as the parents who go the extra mile for their kids are exactly *not* the problem. Instead, we want to target the overworked, stressed, dead-beat, angry, confused, overwhelmed, etc. parents. These parents are not in a position to make good choices, they are barely able to keep it together as it is. They won't be signing up for special charters, enforcing homework, looking out for their children. And these kids are the ones who are the dirty little secret behind "bad" schools.

Traditional schools continue to fail them, with neither the funding nor comprehensive strategy to deal with them. Charters just plain avoid them.

But they are the result of a larger economic system which segregates by property value. Middle class neighborhoods populate schools with children of middle class parents and all the stability that represents. Poor neighborhoods populate schools with children of poor parents and all the lack of stability that represents.

I have two ideas for intervention. The first is to simply implement economic integration. Each school must have a certain percentage from different socio-economic levels. If you really wanted to get creative, you could create an SES scale that goes beyond mere income, and takes into account things like education, health, family support, issues, etc. (all of the the contingencies that go into supporting the development of a child). Families would be assigned a score based on filling out a new card each year. This would require a certain level of busing, which has its downsides. But it would "spread the hardship" across our neighborhood schools. There would likely be some downwards pressure from these struggling kids on the rest of the student body. But there would likewise be upwards pressure from the rest of the students. However, with this method, you're still not directly addressing the particular need of the student. With a 30:1 ratio, and few other interventions, stressed out kids in stressed families who don't do their homework or get read to at night will still be highly at-risk. The other way of going at this would be to incentivize economic desegregation by offering tax rewards to poor families who move out of poor communities and wealthier families who move in. This brings up a gentrification worries for many, as ethnicity is so tied to income. Personally, I wonder if actual economic desegregation wouldn't make the notion of gentrification irrelevant though.

A second option would be to forget busing, and focus on interventions at the local level instead. Poor schools would get 10x the funds, the ability to cut class sizes by a half or even two-thirds. Instruction and support would be much more differentiated to the needs of the individual student. Similar to the

IEP model for students with physical disabilities, every child would get an academic, "wrap-around" team to monitor performance both at school - and as would be central in this case - home. On the television show The Wire, a so-called

"Hamsterdam" experiment was invented, in which the police created a decriminalization block where drug users could freely use and pushers to sell their wares. The idea was to end the violence of the trade, and allow the users to come out of the shadows where they would be able to be targeted by social service workers. While poor, struggling families aren't quite drug addicts, I'm struck by the similarities, as well as our social response to their plight - which is a muddled mix of disdain, pity and victim-blaming. Rather, these are fellow humans who need all of our help. The bonus being, of course, eradication of a major source of social ill.

Both of these ideas are radical, but in my view more directly align with our values, and support fundamental notions of fairness in public education. If we must have economic segregation in our capitalist economic system, then we must also reckon with the fact that we are going to be creating segregated economic ghettos, defined by their lack of resources and societal capital.