Apparently, the Sarah Palin's staff is now claiming that the infamous "cross-hairs" campaign poster, pointed to by many as evidence of the kind of overheated right-wing rhetoric that may have led to the Rep. Giffords shooting, was really intended to be a "surveyors" symbol all along. Mark Kleiman points to the broader context and the right-wing pattern of using the language of violence.

The political debate over the degree to which rhetoric played a role in the shooting, if any at all, has been polarized as usual. The refrain on the right is defensive, and points to evidence of extreme rhetoric on the left during the Bush years. But this seems pretty wrong to me. I'd pose a couple of questions.

First, is it true that there is a lot of extreme, dishonest and dangerous rhetoric coming from the right? And second, is there an equivalent amount coming from the left – either now, or in the past 10-20 years?

I used to listen to a lot of AM radio in the 90′s – Michael Savage in SF. When Oklahoma City happened it seemed to fit right into the paranoid narrative: the government is illegitimate, conspiracy theories and the endless likening of liberalism to creeping communism. This was all over the airwaves. The callers would frequently start talking about violent revolution, the hosts muting them with a wink. If anything, the rhetoric seems to have gotten worse, with FOX news turning up the volume to eleven.

I don’t ever remember things getting this bad on the left, even during the worst days of the Bush administration, from the left’s perspective. I think there are numerous reasons for this, the largest being the left’s disinterest in guns and violence in general, as a cultural matter. What I don’t understand though, is the right’s seeming willingness to be entertained by so many obviously immoral media personalities. And I mean immoral in the sense that they are routinely meanspirited and dishonest. They revel in ad hominem attacks, and traffic endlessly in overgeneralizations and transparent falsehoods. The left just has never had this. AM radio is completely dominated by the right. MSNBC is giving FOX a run for their money, but their audience pales in comparison.

I suppose you could chalk some of this up to the generally liberal, or at least centrist, slant of the mainstream media, which likely alienates many rural and conservative citizens. But how could you trade something like NPR for Rush Limbaugh? What am I missing? Why isn’t there at least an NPR equivalent on the right, something that attempts serious journalism, treats people with respect and isn’t more akin to the Jerry Springer show than intellectual engagement? Given the obviously large size of American conservatism, fact that there hasn’t been anything built up on the right that isn’t largely mean, dishonest or vapid would seem distressing. If all liberals seemed to be interested in was a sort of Air America-style format, I’d really worry about the seriousness of the left.

A bastard's take on human behavior, politics, religion, social justice, family, race, pain, free will, and trees

Sunday, January 9, 2011

Saturday, January 8, 2011

Discussing Ed Reform on Bloggingheads

My bloggingheads dialogue on education reform is up. Here's the link.

Saturday, January 1, 2011

Looking for Any Excuse

|

| Brookside Mill workers in 1910, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA |

A new regime in state politics is venting frustration less at Goldman Sachs executives (Governor Christie vetoed a proposed “millionaire’s tax” this year) than at unions.This is an interesting point. There is a clear calculus being made here that unionized public sector workers are somehow less deserving of the need to sacrifice than millionaires. This, despite the fact that most public workers clock in at the low end of the middle class pay scale.

The philosophical basis for this distinction is rooted in the conservative, meritocratic fallacy that millionaires not only deserve their wealth because of hard work, but are the active engines of economic growth. Therefore, taxing their income would actually stifle growth. The essential image of this picturesque fantasy is one of every millionaire out there starting new businesses or investing their money in growth-industries. Of course, when speaking of tax breaks of $20-30K, none of these individuals is indulging in zero-sum consumption - in which their spending produces no net gain in growth; i.e. jewelry, fine leather goods or vacations in Aspen. Of course not.

Yet what seems particularly more irksome than the notion that millionaires are magic growth machines, is the idea that lowly non-millionaires are of negligible worth to society. Now, maybe I'm getting ahead of myself... maybe these outraged Americans do actually value the public service workers who spend their days working for the very same "government" despised by those outraged, and who perform jobs they would just as soon not have them do at all.

But even supposing these workers are valued, why expend so much energy trying to cut back on their salaries and benefits while sparing the marginal rates of the very wealthy, unless you fundamentally don't believe those jobs are worth doing. As the article notes, simply acting out of a sense of fairness would seem spiteful.

All of which sounds logical, except that, as Mr. Moriarty also acknowledges, such thinking also “leads to a race to the bottom.” That is, as businesses cut private sector benefits, pressure grows on government to cut pay and benefits for its employees.An increasingly familiar complaint is that anyone should expect a pension at all. On a recent episode of 60 minutes, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie flat out asked the question:

I think the general public thinks, 'I can't believe anybody gets a pension anymore. I've got a 401(k). It got killed in the stock market. I don't know what I'm gonna do for my retirement. I can't believe people get a pension anymore.'Well, we know what Governor Christie thinks. You know, maybe the minimum wage is a bad idea too. And maybe costly workplace safety regulations. Or overtime pay.

I think we know where this is heading. We've literally been there before, and conservatives are itching to take us right back. And a recession is as good an excuse as any.

Invisible Radicals (cont.): Who Determines Equality?

I had originally written the majority of my previous post as a comment at the RBC. I received two interesting responses:

A.

B.

Believe me, I would like as little government intervention as possible. As you'll note though, a more means-tested system would allow for less government in many neighborhoods. The ultimate goal is smarter government, so that we can get the kids the targeted services they need, when they need them, and not when they don't.

But you make an interesting point, and something I struggle with as a teacher in these populations. It is an empirical fact that SES is tied to parenting. This is not simply my idea of what is acceptable. There are activities that you do with your child that produce better developmental outcomes. Studies have been done in granular detail, looking at everything from environmental toxins to vocabulary to cognition to family structure. Believe me, I've sat across from many parents who I knew were not providing their children the best home environment. And as a white guy from a middle class background (both parents attended college, and statistically most teachers are from similar backgrounds), there's a definite sense of invasiveness to the class dynamic. Who am I to be telling them how to raise their kids when I haven't had the struggles they've had? (Short answer: I'm a teacher!)

But you know what - it all comes out in the wash. Poor parents have every reason to parent exactly the way they do (statistically!). They are doing the best they can - so what if it isn't the best? This is what society is all about - helping each other out. Every parent I've ever had cared deeply about their child. They just may have lacked the proper skills (or circumstances) to offer them what they needed. They didn't read to them at night, they never learned English, they never took them to the library, they scolded more than praised, they didn't engage in extended conversation - not because they didn't love their kids, but because they simply weren't aware of the effects this would have on their child's development.

But the reality is that we're just not going to be able to "retrain" parents. And there are many areas of their lives that are beyond anyone's ability to reform. For instance, if they are working two crappy jobs to pay the rent and are stressed because the boss is a prick, and can't spend enough time with their child as they'd like because Dad is either gone or in prison. Or there's drugs. Or abuse. Etc. But there are interventions that can help ease their burden, and in turn the burden on their child. And there are specific interventions we can do to provide support directly to the child, whether for special field trips on weekends, after-school tutoring/camp, psychological services, radically smaller class sizes - 10:1 ratio, personal aids, etc. Those are all things that parents don't have to worry about at all and honestly, most parents would welcome.

And at the end of the day it is all about outcomes. An assessment regime would be tricky. But as the child improves, the services would dial back accordingly, with the ultimate goal of removing the supports entirely. This is generally the model for special education and english-language-learners. The interesting thing is those "disabilities" appear values neutral, as they are not the "fault" of anyone. But I would argue that no one's parenting style is the "fault" of anyone either. We all have a set of skills from which we operate. Those skills involve cognition, emotion, communication, knowledge of self, stress management, etc.

Obviously this is the black box of the mind and things get messy real quick. But the central dogma is that we are developed creatures, and operate from learned behavior. Depending on a mix of genes and environment, we apply what we know to the world. This is why a poor 16 year old girl is likely to be a lousy mother. It isn't her fault - she just doesn't have the proper skills. I think most of us take all of this for granted and we buy into the mythology that every individual possesses the same abilities.

I think much of this comes out of a tension between those who might emphasize innate differences to explain behavioral outcomes, leaving "free will" to explain the rest (interestingly, the philosophical description of this is "metaphysical libertarianism" - the political philosophy seems largely to follow), while others emphasize the environment and learning. The former view seems entirely commonsensical - I choose to get to work on time, I choose to take a bath. Yet so does the latter - I've learned to manage my time, I've learned that proper hygiene is important. The compatibilist (I believe) seeks to reconcile these two as: I've learned to do these things and so I am able to choose them.

To me, this provides for the most powerfully compassionate response to poverty. Being neither condescending nor punitive, it simply acknowledges empirical fact, and supports our human desire to uphold our values of liberty and equality of opportunity. How exactly we get there is certainly unclear. But the moral directive is strong, and there are many promising avenues available.

A.

“equity in achievement”? People DO differ in potential, the only way to achieve this sort of equity is to deliberately fail those who could do better than what the less gifted can achieve. Our goal, (After a learned workforce, of course.) should be to enable each individual student to achieve their own potential, even if it means they leave somebody else in the dust.

B.

Your description of what it would take to get to [equity in achievement] paints the picture of a very intrusive set of interventions. Well-meaning and perhaps not individually burdensome, but still intrusive. I have family members who would no doubt qualify for these interventions, and have to say that some of them sound as if you want to take my relatives and turn them into your idea of acceptable parents.By "equity in achievement" I don't mean that every single child performs exactly the same. I mean that SES is limited in it's impact on educational outcomes, such that each individual student really does have an opportunity to achieve their own potential. As it stands now, academic performance is strongly tied to SES. But this has nothing to do with the individual student, and everything to do with the social capital they receive at home (educated parents, intact families, less stress, etc.).

Believe me, I would like as little government intervention as possible. As you'll note though, a more means-tested system would allow for less government in many neighborhoods. The ultimate goal is smarter government, so that we can get the kids the targeted services they need, when they need them, and not when they don't.

But you make an interesting point, and something I struggle with as a teacher in these populations. It is an empirical fact that SES is tied to parenting. This is not simply my idea of what is acceptable. There are activities that you do with your child that produce better developmental outcomes. Studies have been done in granular detail, looking at everything from environmental toxins to vocabulary to cognition to family structure. Believe me, I've sat across from many parents who I knew were not providing their children the best home environment. And as a white guy from a middle class background (both parents attended college, and statistically most teachers are from similar backgrounds), there's a definite sense of invasiveness to the class dynamic. Who am I to be telling them how to raise their kids when I haven't had the struggles they've had? (Short answer: I'm a teacher!)

But you know what - it all comes out in the wash. Poor parents have every reason to parent exactly the way they do (statistically!). They are doing the best they can - so what if it isn't the best? This is what society is all about - helping each other out. Every parent I've ever had cared deeply about their child. They just may have lacked the proper skills (or circumstances) to offer them what they needed. They didn't read to them at night, they never learned English, they never took them to the library, they scolded more than praised, they didn't engage in extended conversation - not because they didn't love their kids, but because they simply weren't aware of the effects this would have on their child's development.

But the reality is that we're just not going to be able to "retrain" parents. And there are many areas of their lives that are beyond anyone's ability to reform. For instance, if they are working two crappy jobs to pay the rent and are stressed because the boss is a prick, and can't spend enough time with their child as they'd like because Dad is either gone or in prison. Or there's drugs. Or abuse. Etc. But there are interventions that can help ease their burden, and in turn the burden on their child. And there are specific interventions we can do to provide support directly to the child, whether for special field trips on weekends, after-school tutoring/camp, psychological services, radically smaller class sizes - 10:1 ratio, personal aids, etc. Those are all things that parents don't have to worry about at all and honestly, most parents would welcome.

And at the end of the day it is all about outcomes. An assessment regime would be tricky. But as the child improves, the services would dial back accordingly, with the ultimate goal of removing the supports entirely. This is generally the model for special education and english-language-learners. The interesting thing is those "disabilities" appear values neutral, as they are not the "fault" of anyone. But I would argue that no one's parenting style is the "fault" of anyone either. We all have a set of skills from which we operate. Those skills involve cognition, emotion, communication, knowledge of self, stress management, etc.

Obviously this is the black box of the mind and things get messy real quick. But the central dogma is that we are developed creatures, and operate from learned behavior. Depending on a mix of genes and environment, we apply what we know to the world. This is why a poor 16 year old girl is likely to be a lousy mother. It isn't her fault - she just doesn't have the proper skills. I think most of us take all of this for granted and we buy into the mythology that every individual possesses the same abilities.

I think much of this comes out of a tension between those who might emphasize innate differences to explain behavioral outcomes, leaving "free will" to explain the rest (interestingly, the philosophical description of this is "metaphysical libertarianism" - the political philosophy seems largely to follow), while others emphasize the environment and learning. The former view seems entirely commonsensical - I choose to get to work on time, I choose to take a bath. Yet so does the latter - I've learned to manage my time, I've learned that proper hygiene is important. The compatibilist (I believe) seeks to reconcile these two as: I've learned to do these things and so I am able to choose them.

To me, this provides for the most powerfully compassionate response to poverty. Being neither condescending nor punitive, it simply acknowledges empirical fact, and supports our human desire to uphold our values of liberty and equality of opportunity. How exactly we get there is certainly unclear. But the moral directive is strong, and there are many promising avenues available.

Friday, December 31, 2010

The Invisible Radicals

Michael O'Hare appends a thoughtfully-commented post on education reform with a call for, well, what amounts to better teaching and more effective pedagogical suggestions. Yet he makes what I think is a common mistake in the current reform debate: he raises the specter of the achievement-gap, yet then prescribes common educational practices which are routinely found in higher SES schools, yet less common in poor schools, as a substantial solution. By emphasizing classroom instruction and ignoring the more powerful and destructive ways in which SES disadvantages children, he unknowingly promotes the very attitudes that have lead to a continuation of the achievement gap.

He begins his piece by making the reasonable observation that calls for instructional reform need not imply a devaluation of other efforts at reform.

This is a good point on its own. But policy is political, and some ideas are going to be pushed more than others. I'd say the emphasis on good vs. bad teaching right now is about 90% of the debate. That is, it is assumed that we can close the achievement gap through figuring out how to get better teaching. Just look at the Obama administration's policy agenda: charters, accountability, standards, pay for performance - all focused on the teacher. Implicit in this overwhelming focus is an assumption is that most of the problem problem is in teaching itself. It would be as if we we were riding a bus headed for a cliff and everyone was screaming that what we really needed to do is roll down the windows and reduce air flow with our hands.

In my view, the problem is much greater, and involves the larger and much more intractable problem of poverty and disadvantaged parents unable to properly support their children at home. If you look at schools where kids are getting good support at home, "bad teaching" simply isn't an issue. But we don't talk about this anymore. The left and right have converged around the idea that the standard model is fine, and all we need to do is tweak the teaching.

Here's another metaphor: two mountain climbing guides each have a group of hikers he needs to get to the top of the mountain. One group is properly trained, has the right gear, is well-nourished and excited to work hard. The other group is poorly trained, has broken gear, malnourished, depressed and uninterested in climbing at all. Should we give each guide the same resources, and expect them to take their hikers the same distance each day? No, that would be silly. If we were smart we would would still expect both to do their job (obviously), but we should find ways of supporting them and their hikers so that they had a chance in hell of actually making it to the top of the mountain.

We mention pre-K in passing, and it is on the table. But it is kind of the beginning and the end of the acknowledgment that SES plays a role in the achievement gap (pre-K is essentially intervention for the poor). But the extra support ends when they enter kindergarten. Suddenly it is is entirely up to the classroom teacher, with no extra resources, to take each severely disadvantaged kid and make adequate progress.

What if we treated SES the way we treat special education? What if we did an initial assessment, then targeted students for support services as a part of a legal mandate to take their disadvantage seriously? This could mean anything from after-school tutoring to a one-on-one aid, to a social worker who acts as a liaison between the school and home, to home-health visits and parenting classes? All of this of course backed up with extra funding. We do it with reduced-price/free lunches. We acknowledge an SES nutrition gap.

But proper nutrition is just the tip of the iceberg. What other risk-factors exist that affect academic performance? There are many. It's all in the literature. But the problem is in assessment. How do you determine the level of cognitive stimulus a child receives at home? Or stress levels? There are broad predictors such as parent education. But how do you get at specific, targeted needs? There are a variety of ways you can go - maybe routine home visits, maybe starting from birth, maybe a centralized system of sharing between case-workers, teaching staff, counselors and health workers. The goal would be to treat the whole child and develop protocols for intervention that provide support for classroom instruction.

Due to cost, and - probably subsequent - philosophical intransigence, there just haven't been that many large studies of this sort of comprehensive approach to what I'd call "Student Capital Intervention". There have been many small programs which provide rudimentary evidence for this type of thing being successful. I think it is well supported in theory - we know that great gaps exist in family/neighborhood impact on development. But we need more studies that tie specific treatment programs to academic success. But these kinds of longitudinal studies involving multifaceted care are very difficult.

But ultimately, if we remember just what it is we are facing (large-scale poverty and social dysfunction), and what kinds of results we are expecting (equity in achievement by graduation), we will inevitably be faced with the fact that any serious reform will require a massive and radical reformation of what public education looks like. The good news is that we are wasting countless hours and dollars on efforts that will produce marginal results. So, if we were somehow able to shift all that effort into the kind of meaningful reform I've discussed, much of the cost will be offset.

More money could also be found in a reworking of the tradition model of resource allocation. So for instance, my daughter's school is largely a high human and social capital demographic. Educated parents, intact families, reasonably affluent - all providing invaluable resources to the student population. Not only is parent volunteerism high, but fund-raising routinely brings in roughly 30X that of a low-SES school. So if we moved toward a more means-tested model, we could save considerably. (Of course, there might be considerable political push-back here.)

I'm not naive in thinking that this has a chance of happening any time soon. But I do think it is inevitable as long as we are reasonably interested in closing the achievement gap. Presently, it isn't even really on the radar. But I think there is a great deal of "invisible support" for something like it, both from teachers as well as from researchers across the nation.

Interestingly, it's a vaguely acknowledged piece of Geoffrey Canada's Harlem Children's Zone, which spends around 3x per pupil. Yet even there, he's managed to thread an interesting political needle between the teacher-reform crusaders and the human/social capital intervention models that target what research has found to be the primary driver of the achievement gap. As it stands, indications are that the HCZ's success has had more to do with student selection than its smattering of support programs, which are far from the comprehensive regime I've argued for (most recipients of HCZ support programs aren't actually educated in its schools and whose academic outcomes are not being tracked in any kind of substantial way).

Yet there is research that has supported the efficacy of similar types of programs, although much more work needs to be done. Given that we are probably at least a decade a way from the realization that our current trajectory is destined for general failure, we'll certainly have time to lay more of the groundwork. Interestingly, a few court cases have moved in the direction of finding constitutional support for the idea that students have a right to a proper education - leaving of course the proper policy path up to debate. But a legal grounding will come in handy when we realize that more investment will be needed if we are to engage the larger and more difficult problem of SES and education.

He begins his piece by making the reasonable observation that calls for instructional reform need not imply a devaluation of other efforts at reform.

"the instinctive, desperate, desire to believe that a problem has one solution–that advocacy of a reform or practice improvement must be hostile to other possible approaches–is a really big problem. If home environment, parents, and peers matter a lot for learning (of course they do!), trying to hire and train better teachers can’t make a difference, right? Wrong. We can do lots of useful mutually complementary things to improve student learning at all levels, and being paralyzed with doubt because we might be pushing the third most efficacious of these rather than the first is just silly. "

This is a good point on its own. But policy is political, and some ideas are going to be pushed more than others. I'd say the emphasis on good vs. bad teaching right now is about 90% of the debate. That is, it is assumed that we can close the achievement gap through figuring out how to get better teaching. Just look at the Obama administration's policy agenda: charters, accountability, standards, pay for performance - all focused on the teacher. Implicit in this overwhelming focus is an assumption is that most of the problem problem is in teaching itself. It would be as if we we were riding a bus headed for a cliff and everyone was screaming that what we really needed to do is roll down the windows and reduce air flow with our hands.

In my view, the problem is much greater, and involves the larger and much more intractable problem of poverty and disadvantaged parents unable to properly support their children at home. If you look at schools where kids are getting good support at home, "bad teaching" simply isn't an issue. But we don't talk about this anymore. The left and right have converged around the idea that the standard model is fine, and all we need to do is tweak the teaching.

Here's another metaphor: two mountain climbing guides each have a group of hikers he needs to get to the top of the mountain. One group is properly trained, has the right gear, is well-nourished and excited to work hard. The other group is poorly trained, has broken gear, malnourished, depressed and uninterested in climbing at all. Should we give each guide the same resources, and expect them to take their hikers the same distance each day? No, that would be silly. If we were smart we would would still expect both to do their job (obviously), but we should find ways of supporting them and their hikers so that they had a chance in hell of actually making it to the top of the mountain.

We mention pre-K in passing, and it is on the table. But it is kind of the beginning and the end of the acknowledgment that SES plays a role in the achievement gap (pre-K is essentially intervention for the poor). But the extra support ends when they enter kindergarten. Suddenly it is is entirely up to the classroom teacher, with no extra resources, to take each severely disadvantaged kid and make adequate progress.

What if we treated SES the way we treat special education? What if we did an initial assessment, then targeted students for support services as a part of a legal mandate to take their disadvantage seriously? This could mean anything from after-school tutoring to a one-on-one aid, to a social worker who acts as a liaison between the school and home, to home-health visits and parenting classes? All of this of course backed up with extra funding. We do it with reduced-price/free lunches. We acknowledge an SES nutrition gap.

But proper nutrition is just the tip of the iceberg. What other risk-factors exist that affect academic performance? There are many. It's all in the literature. But the problem is in assessment. How do you determine the level of cognitive stimulus a child receives at home? Or stress levels? There are broad predictors such as parent education. But how do you get at specific, targeted needs? There are a variety of ways you can go - maybe routine home visits, maybe starting from birth, maybe a centralized system of sharing between case-workers, teaching staff, counselors and health workers. The goal would be to treat the whole child and develop protocols for intervention that provide support for classroom instruction.

Due to cost, and - probably subsequent - philosophical intransigence, there just haven't been that many large studies of this sort of comprehensive approach to what I'd call "Student Capital Intervention". There have been many small programs which provide rudimentary evidence for this type of thing being successful. I think it is well supported in theory - we know that great gaps exist in family/neighborhood impact on development. But we need more studies that tie specific treatment programs to academic success. But these kinds of longitudinal studies involving multifaceted care are very difficult.

But ultimately, if we remember just what it is we are facing (large-scale poverty and social dysfunction), and what kinds of results we are expecting (equity in achievement by graduation), we will inevitably be faced with the fact that any serious reform will require a massive and radical reformation of what public education looks like. The good news is that we are wasting countless hours and dollars on efforts that will produce marginal results. So, if we were somehow able to shift all that effort into the kind of meaningful reform I've discussed, much of the cost will be offset.

More money could also be found in a reworking of the tradition model of resource allocation. So for instance, my daughter's school is largely a high human and social capital demographic. Educated parents, intact families, reasonably affluent - all providing invaluable resources to the student population. Not only is parent volunteerism high, but fund-raising routinely brings in roughly 30X that of a low-SES school. So if we moved toward a more means-tested model, we could save considerably. (Of course, there might be considerable political push-back here.)

I'm not naive in thinking that this has a chance of happening any time soon. But I do think it is inevitable as long as we are reasonably interested in closing the achievement gap. Presently, it isn't even really on the radar. But I think there is a great deal of "invisible support" for something like it, both from teachers as well as from researchers across the nation.

Interestingly, it's a vaguely acknowledged piece of Geoffrey Canada's Harlem Children's Zone, which spends around 3x per pupil. Yet even there, he's managed to thread an interesting political needle between the teacher-reform crusaders and the human/social capital intervention models that target what research has found to be the primary driver of the achievement gap. As it stands, indications are that the HCZ's success has had more to do with student selection than its smattering of support programs, which are far from the comprehensive regime I've argued for (most recipients of HCZ support programs aren't actually educated in its schools and whose academic outcomes are not being tracked in any kind of substantial way).

Yet there is research that has supported the efficacy of similar types of programs, although much more work needs to be done. Given that we are probably at least a decade a way from the realization that our current trajectory is destined for general failure, we'll certainly have time to lay more of the groundwork. Interestingly, a few court cases have moved in the direction of finding constitutional support for the idea that students have a right to a proper education - leaving of course the proper policy path up to debate. But a legal grounding will come in handy when we realize that more investment will be needed if we are to engage the larger and more difficult problem of SES and education.

Monday, December 27, 2010

Gucci Bags in Wartime

David Halperin and Katherine Mangu-Ward discuss the role of the government in higher education. Mangu-Ward argues the libertarian position - that rather than a force for good in helping striving Americans achieve a better life through college by subsidizing student loans, the government is not only driving up the cost of college tuition, but devaluing the credential itself by over-extending it in the market. What's more, it is doing inefficiently what private banks could do on their own. (One almost waits for her to then start in on the dubious line about how these dumb "wannabes" don't deserve to college anyway. But thankfully she resists).

A commenter on the interview defended her point of view, framing those who would argue for government subsidies as essentially saying this:

I'll get right to the point. Success is largely social determined. This is so overwhelmingly born out in the research it's not disputable (although, be my guest).

So, social structures are thus leveraged by the advantaged. The fact that there are large demographic trends in college admissions makes this a pretty obvious point. If this is true, then who has actually received the subsidy, the poor kid from a crappy neighborhood or the rich kid who's daddy and mommy both graduated from college?

You can argue this sort of "redistribution" is inefficient (as Mangu-Ward does). But that applies just as well to every "common good" service, aka that which is for the good of the society at large. Schools, parks, military, roads, libraries, etc. are more efficient in every way except one: doing it for the public good. Democracy requires legislation, accountability, etc. Not to mention provision of service with the express belief in the right of citizens to some level of access.

So, public libraries have to spend more to clean up after the homeless people you allow in. Police have to answer every 911 call. Schools have to provide special services to the disabled. And they have to do it all in conditions of incredible revenue uncertainty. This can severely hamper asset allocation. Much of the time government is spent in a mad scramble after a fickle public.

These sort of inefficiencies might be too high a price to pay for some. But they should at least acknowledge behind the sacrifice. We all have values and we seek to align our government along side them. I happen to think that the mentally ill have gotten a raw deal in life and ought to receive the very best treatment society can pay for - at least while there are still luxury goods being consumed. That's my America.

A better, more "values-neutral" position might be on an alien invasion (I imagine the prospects of being enslaved by a bloodthirsty alien race seeking to harvest our organs would be pretty universally uncomfortable). So would we not want every last available resource martialed toward defending against the invaders? Of course we would. Gucci bags in wartime are most conspicuous.

OK, well maybe aliens are a stretch - but we only have to go back to WWII to see what a nation is willing to sacrifice when they feel the cause is worth it. In that case, the only alternative was certain Nazi subjugation. I can guarantee you that anyone foolish enough to raise a fuss about "big government" and insisting the war be fought by private armies because of their efficiency would have been given a swift kick in the arse.

Maybe I need to get very specific here: being enslaved by the Nazis is about as anti-freedom as you can get. Especially if you're Jewish, right? Death isn't very liberating. And neither is totalitarianism or torture. The point is that these experiences were so frightening that we were willing to sacrifice just about anything to avoid them happening to us.

How different then is growing up in poverty, or sleeping under a bridge because of the voices in your head? Or how about being a single mom who can't afford childcare for her kids? Or needing health insurance but not being able to afford it - or denied it because of a pre-existing condition? Or being old and not having money to pay the heating bill? Or even just not being able to go to college and better yourself because there is no practical way to do so without government help. I've worked plenty of minimum wage jobs and they felt nothing if not oppressive. There is always the trades, but even then, being forced into a lot in life that you were forced into choosing seems the antithesis of freedom at best.

Yet when the liberal response to these social problems is government intervention, the specter of "big government" is raised. The basic premise being disagreed with is the specific quality of each form of suffering. Nazis = bad, lots of death and rape = government intervention OK. But poverty, food stamps, drug addiction = not really so bad, maybe they deserve it = government intervention not OK.

I think what is most troubling for liberals is that we see these problems as just being very sad and we feel a moral compulsion to respond in a way that no one should have to experience them, even if it requires paying for an expensive and possibly inefficient infrastructure. The moral case is just that strong.

There are certainly philosophical principles that lead us here. We don't believe, for instance that these people truly chose their fate, as many (all?) on the right do. Neither do we feel that everyone should be given everything for free; it is hard to find a liberal these days that doesn't believe in a strong market system in which much of life is indeed ruled by the market.

But what liberalism is definitely not is a solution in search of a problem: that we aren't really concerned with social problems and just want more government for the fun of it - or to waste the money of the rich! This would be akin to claiming the right wants to spend money on the military and war just for the fun of it. Actually, one might say there is something sort of fetishistic about guns on the right. Maybe one day the left will get food stamp Barbie. I'm reminded now of the game Monopoly being so fun as a celebration of pure greed and competition. Games involving empathy, humility and sharing - values glorified on the left - are few and far between. (Ironically, Monopoly itself was popularized by Quakers and based on The Landlord's Game, a board game designed to show how rents "enriched property owners and impoverished tenants".)

And so, I suppose we've come full-circle - back to who owns what, and where we come from. The evidence for distinct structural mechanisms for class-determinism in America is really unassailable. Although many will continue to try. The reason for this is clear: to acknowledge it would generate a considerable amount of cognitive dissonance within the right-wing mind. If people are not freely choosing their lot in life, then a moral wrong is occurring. In the end, it is all about liberty.

A commenter on the interview defended her point of view, framing those who would argue for government subsidies as essentially saying this:

"Shut up and pay up so people like me can go to school for free."Ignoring the absurdity that anyone is "going to school for free", the general idea is that the moochers are weaseling the rich out of their money by getting federal and state college subsidies.

I'll get right to the point. Success is largely social determined. This is so overwhelmingly born out in the research it's not disputable (although, be my guest).

So, social structures are thus leveraged by the advantaged. The fact that there are large demographic trends in college admissions makes this a pretty obvious point. If this is true, then who has actually received the subsidy, the poor kid from a crappy neighborhood or the rich kid who's daddy and mommy both graduated from college?

You can argue this sort of "redistribution" is inefficient (as Mangu-Ward does). But that applies just as well to every "common good" service, aka that which is for the good of the society at large. Schools, parks, military, roads, libraries, etc. are more efficient in every way except one: doing it for the public good. Democracy requires legislation, accountability, etc. Not to mention provision of service with the express belief in the right of citizens to some level of access.

So, public libraries have to spend more to clean up after the homeless people you allow in. Police have to answer every 911 call. Schools have to provide special services to the disabled. And they have to do it all in conditions of incredible revenue uncertainty. This can severely hamper asset allocation. Much of the time government is spent in a mad scramble after a fickle public.

These sort of inefficiencies might be too high a price to pay for some. But they should at least acknowledge behind the sacrifice. We all have values and we seek to align our government along side them. I happen to think that the mentally ill have gotten a raw deal in life and ought to receive the very best treatment society can pay for - at least while there are still luxury goods being consumed. That's my America.

A better, more "values-neutral" position might be on an alien invasion (I imagine the prospects of being enslaved by a bloodthirsty alien race seeking to harvest our organs would be pretty universally uncomfortable). So would we not want every last available resource martialed toward defending against the invaders? Of course we would. Gucci bags in wartime are most conspicuous.

OK, well maybe aliens are a stretch - but we only have to go back to WWII to see what a nation is willing to sacrifice when they feel the cause is worth it. In that case, the only alternative was certain Nazi subjugation. I can guarantee you that anyone foolish enough to raise a fuss about "big government" and insisting the war be fought by private armies because of their efficiency would have been given a swift kick in the arse.

Maybe I need to get very specific here: being enslaved by the Nazis is about as anti-freedom as you can get. Especially if you're Jewish, right? Death isn't very liberating. And neither is totalitarianism or torture. The point is that these experiences were so frightening that we were willing to sacrifice just about anything to avoid them happening to us.

How different then is growing up in poverty, or sleeping under a bridge because of the voices in your head? Or how about being a single mom who can't afford childcare for her kids? Or needing health insurance but not being able to afford it - or denied it because of a pre-existing condition? Or being old and not having money to pay the heating bill? Or even just not being able to go to college and better yourself because there is no practical way to do so without government help. I've worked plenty of minimum wage jobs and they felt nothing if not oppressive. There is always the trades, but even then, being forced into a lot in life that you were forced into choosing seems the antithesis of freedom at best.

Yet when the liberal response to these social problems is government intervention, the specter of "big government" is raised. The basic premise being disagreed with is the specific quality of each form of suffering. Nazis = bad, lots of death and rape = government intervention OK. But poverty, food stamps, drug addiction = not really so bad, maybe they deserve it = government intervention not OK.

I think what is most troubling for liberals is that we see these problems as just being very sad and we feel a moral compulsion to respond in a way that no one should have to experience them, even if it requires paying for an expensive and possibly inefficient infrastructure. The moral case is just that strong.

There are certainly philosophical principles that lead us here. We don't believe, for instance that these people truly chose their fate, as many (all?) on the right do. Neither do we feel that everyone should be given everything for free; it is hard to find a liberal these days that doesn't believe in a strong market system in which much of life is indeed ruled by the market.

But what liberalism is definitely not is a solution in search of a problem: that we aren't really concerned with social problems and just want more government for the fun of it - or to waste the money of the rich! This would be akin to claiming the right wants to spend money on the military and war just for the fun of it. Actually, one might say there is something sort of fetishistic about guns on the right. Maybe one day the left will get food stamp Barbie. I'm reminded now of the game Monopoly being so fun as a celebration of pure greed and competition. Games involving empathy, humility and sharing - values glorified on the left - are few and far between. (Ironically, Monopoly itself was popularized by Quakers and based on The Landlord's Game, a board game designed to show how rents "enriched property owners and impoverished tenants".)

And so, I suppose we've come full-circle - back to who owns what, and where we come from. The evidence for distinct structural mechanisms for class-determinism in America is really unassailable. Although many will continue to try. The reason for this is clear: to acknowledge it would generate a considerable amount of cognitive dissonance within the right-wing mind. If people are not freely choosing their lot in life, then a moral wrong is occurring. In the end, it is all about liberty.

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

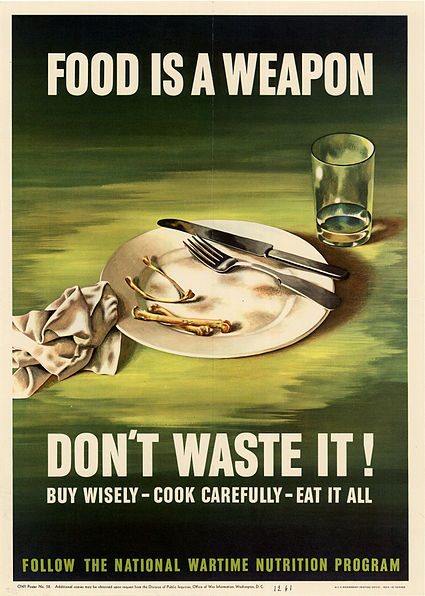

Propaganda Works

|

| Santi di Tito: Niccolò Machiavelli |

A recently leaked FOX news memo from 2009 shows explicit instructions being given for reporters to refer to the "government option" instead of the "public option". Apparently this directive was informed by Republican pollster Frank Luntz who had found that people found the term "government" less favorable than "public".

Just goes to show how powerful propaganda is. The right has been relentless in their campaign to make government into a dirty word. If they were honest, they would say "certain types of government". But then they're starting to sound like Democrats - you know, acknowledging nuance, putting things in context, speaking clearly and without misleading and dishonest overgeneralizations.

But hey - it works. Maybe if we start talking about government libraries, government parks, government education, and government-works projects we'll really save the Galts some cash.

At the risk of going full-bore partisan here, let me just ask why the right seems so much more comfortable with dishonesty. As exhibit A let me just introduce basically every AM radio personality. "Lying" might sound too offensive, so how about a continuous stream of half-truths and mischaracterizations. And then there's the anger and hatred. It's been a while since I've stomached a listen, but I remember a lot of schoolyard name-calling, yelling, and endless ad-hominem attacks on "liberals": retarded, mentally ill, out to destroy America, etc.

I mean, when I meet people like that in real life, I get really creeped out. The general word for them is "A-hole" or "bully". So why are they so integral to conservatism's trajectory in the past few decades? We've got a few random people on the left who are comparable, but they're hard to find. NPR would be a much more accurate picture of what is driving left-wing debate. Although even there, the idea that NPR "drives" politics in the same way as a Glenn Beck or Limbaugh is kind of ridiculous.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)