Libertarian Mathew Kahn argues that climate change is real, however in our attempts to adapt to it, we ought not incentivize irrational choices, such as building levees so that people can continue to live in low-lying areas.

Humans are incredibly irrational decision makers. Assuming they are not underlies our greatest tendencies to apologize for inequality and injustice. We tell ourselves, "It is their own fault. They could have done differently. They made a rational choice." Yet again and again, we see that people do not. Any businessman who has ever depended on advertising knows this well. Any politician who has calculated his message knows this. Any one who has struggled with diet, a budget, or quitting smoking knows this.

The problem is that it is near impossible to understand the irrational drivers of our own behavior. With great work, we can find ways to counteract this irrationality, but it is largely in the darkness that we work. God knows what it is that is driving you to take that bite of the fattening donut? Your bad childhood? The time you spent reading Zorba the Greek? An impulsive temperament? All the brain research and psychology that exists can only give us the faintest hints. The fact is that the causal mechanisms at work in any given second, when each of our billions of neurons involved in the choice is firing off with its 7000 connections, making up the entirety of consciousness and unconsciousness, is unfathomable.

We learn to counteract the irrationality, in order to supposedly act more rationally. Yet are we really acting more rationally, or have we simply been able to design habits for ourselves that have out-maneuvered the negative impulses? "Rationality" is merely shorthand for *choosing the correct option*.

In a fundamental way, society can be thought of as a vast, evolving system of habit formation. At the individual level, we feel very rational and "in control". But at the macro level, patterns emerge that tell a very different story. Instead of individual, rational actors we see the products of systems such as family, peer relations, education, government, and social norms that conspire to design not only an individual's ability to make correct choices, but - more foundational still - an individual's ability to design for himself the ability to make correct choices. Thus, the choice as whether to eat the donut or not is dependent not only on an individual's choice, but the individual's prior ability to have designed for himself the ability to make that choice. For instance, after week three of having successfully fought the 8am donut cravings, the choice to not eat the donut will be far easier than it was on day one. (I'm not actually hip to diet design, but you get my point: successful routines for habit formation are successful because they are routines, not individual, isolated choices).

So, does this mean that no one ever ought be held accountable? Should we all get to make base, easy, immediately gratifying decisions with no concern for external effects, with the excuse that we had no control? This is generally the first response many have to the argument I have presented. Yet this is a case in which patient, nuanced thinking is called for! If you will recall, I spoke of the element of social design in individual decision-making. Just as we would set for ourselves a course of habit formation that we hope will bring about correct decisions, so too we set for society a course of policy that we hope will bring about correct social behavior. So too we design our formal and informal social institutions. The idea is to look ahead and put in place systems that we hope will flourish. This utilitarianism makes the question of blame somewhat irrelevant. Policies ought be designed that foster, through the mechanics of incentives, social good.

If the question was mere utility, it could be answered by either side of the aisle. It could mean lowering taxes on the "job-creators", harsh sentencing for criminals, or letting residents in low-lying areas suffer rising tides without assistance - the right-wing model. Or it could mean a more left wing emphasis on the benefits of redistribution, leniency, or shared burdens. To the extent that these are subjective, evidence based controversies, the chips will fall where they will.

But what is removed from the equation is the moral posturing that has traditionally been wrapped up in left vs. right politics: no one is to blame. So, even if we will all benefit from "job-creators" getting tax breaks, they are not inherently morally superior by their good works. They have merely been the recipients of social circumstance that have allowed them - being in the right place at the right time - to do good things. We can argue until the cows come home about the extent to which their work is actually good, and how much money is the right incentive for them to continue whatever it is they are doing. But in the end, they are products of *us*, as the saying might go, "we built them".

And so too did we build those who, at the other end of the spectrum, we now see are playing out what society has designed for them in the form of irrational, self-indulgent or poorly-planned behavior. We can also argue about the extent to which these people's behavior is all that bad, or whether by circumstance it appears so (the "negligent mother" may indeed be working two jobs and thus have no ability to look after her delinquent son). But regardless, again, "we built them". So when designing policies that, in the interest of deterrence, or disincentivization, will create hardship on individuals caught in such a tangled web of causality, we must admit that, as they are not the originators of their actions, rather society is to blame, their hardship is a form of Earthly purgatory.

It may allow us to sleep easier at night believing that the many who suffer do so at their own choice. But it is a convenient fiction.

I confess much of this argument is aimed squarely at the right, who though at times concede some degree of social determinism, generally downplay it, if not deny it completely. After all, who then, if not government is going to help enfranchise those whom society has failed to give an equal design? The utilitarian case for less government action is rather weak. And, more noticeably, a great portion of right-wing framing is not utilitarian at all, but rather a direct appeal to an assumed agency ("I built it"), or merely a sense of unfairness at the notion of social design - redistribution is unfair because well, "I built it". The truth is that, were government indeed pared down to only its most basic elements, poverty and class-mobility would not suddenly cease, or even diminish. The supposed moral hazard in provision of social services, or even such things as student loan forgiveness - as former candidate Romney complained about - is a convenient excuse for a callousness that comes from not seeing individuals as determined by social design, whose ability to make rational choices is constrained by a prior ability to develop in themselves this ability, and so on, outwards into the fabric of socialization.

So I'm all for utilitarian incentives. But when their effect is serious hardship in the lives of real people, we must ask ourselves if there was not another, better way to have both incentivized good choices, without having allowed such trauma to have occurred.

A bastard's take on human behavior, politics, religion, social justice, family, race, pain, free will, and trees

Sunday, November 25, 2012

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

Have Faith in Atheism

It must be nice.

That is, having faith in God to pull you through. Having faith that there is a plan for you, having faith that there is a meaning in the universe and a reason for everything.

Of course, no one is without doubt. Even the most devout believers must at times struggle to hold on to their faith. But they have a faith to hold on to. They have a deep and enduring story that, at least in theory, accounts for everything in their lives. It tells of a universe designed with them in mind, with special details and guarantees that promise not only an ultimate reward in the afterlife, but a better life now. It spins tragedy into harmony, grief into glory, pain into love. There may not be any specific answer to specific problems, but in faith it is promised that a deeper purpose exists, and faith will carry one through.

Unfortunately, I have no such reassurances. As an Atheist, I have no reason to believe that there is any higher purpose to my life. The universe was not designed with me in mind. It simply exists, according to a relatively limited set of physical laws. These laws have set in motion an unbelievably vast and complex series of interactions, my body and mind composed of elements forged in the ebb and flow of stellar supernovae, brought together by interactions of gravity and electromagnetics, propelled by energies as distant as the Milky Way galaxy within which our Sun orbits, and as close as the very bonds that hold my sub-atomic particles together. Within this vast cosmic dance, I do my thing.

So, what is "my thing", and more importantly, why do I do it? A question for the ages, right? What is the meaning of life? What is the purpose of life? Having already declared my Atheism, I have already submitted that there is no purpose.

Seven years ago, I tried to kill myself by overdosing on prescription pills. For twenty five years I have gone about my daily life in varying degrees of chronic pain. Sometimes it feels like the walls are closing in all around me. It is all I can do to focus my mental powers like invisible rods and struts, holding back the vice grip of gnawing muscle tension. At other times the pain is barely noticeable, lurking in the background but easily ignored. My life has been torn apart; who knows how it could have been had I not had that surfboard accident in 1989.

In my darkest moments - which thankfully, are much further far and in-between than they used to be before the suicide came as somewhat of a watershed - I do not have God to comfort me. My footsteps are my own. I cannot bend my knee and take solace in a faith that there is a purpose to my pain. There is no "lesson" that I am to learn. There were no sins that I am paying for now, redeemable for a ticket into heaven when I die. There is only the cold machinery of the universe, of which I have been on the receiving end of misfortune.

It is true that we all need purpose. I know as well as anyone what it feels like to reach the end of the tether which attaches me to my will to live. We need a reason to live. We need a reason to push on despite horrible pain, anguish and tragedy. We cannot live without purpose. Purpose is what gives our lives beauty and reminds us in moments of challenge that there is much to be thankful for. Purpose is what drives us to be better, more honest, more caring, more supportive people, to do better things, to set ambitious goals and struggle to accomplish them. Without purpose, our lives become aimless and superficial, stumbling over minor obstacles and sidetracking us towards short-term satisfactions.

If there is no God, or supernatural story within which our lives are fixed, which gives ultimate purpose to our lives, carrying us through the pain and propelling us towards the fulfillment of our best natures, how is it that the Atheist is not destined for all that accompanies a life devoid of purpose?

Some might take solace in the notion that it is Atheism itself which destroys purpose. After all, how can one ever prove that there is no God, or supernatural force that guides our destiny? Partly a semantic issue, Atheism is not incompatible with such agnosticism. It can as easily be said that one can never really prove a negative. Two plus two may equal four this time, but no one can know the future. Just because there is no evidence for God at all, and an inexhaustible supply of evidence for causal mechanisms in the natural world that need no creator to be explained. Aside from the creation of natural laws themselves, we have every reason to believe they are enough in and of themselves to explain everything that exists in the universe. Agnosticism should be the basis not only for supernatural questions, but our stance towards reality itself. However, it is merely a baseline. Acting with purpose requires so much more. While nothing may be able to be completely disproven, we live in a practical world and Occam's Razor requires us to make practical decisions. I may not know that two plus two will always equal four, but I can't sit around waiting to find out. There is just as little purpose in agnosticism as there is in Atheism.

While Atheism can give us no purpose, it makes a stronger statement about purpose in general: that we make our own purpose. In fact, in Atheism we see that all religious faiths (all but one of them being untrue, by default) are in fact man-made. Therefore, the purpose that they purport to offer the faithful is man-made as well.

Unfortunately, as a non-believing Atheist, I cannot simply adopt the purpose of the faithful as my own. And thus I cannot collect the rewards - the comfort, the inspiration. And so I must find my own. Limited to the natural world, I cannot simply invent convenient stories, hiding away in the mysticism that "everything happens for a reason", knowing full well that it doesn't. We offer no such hubris to the billions of animals that die of starvation or predation each year in the wild. The reason? That's life.

But maybe the stoicism of the natural world offers us a clue in how to make sense of a harsh reality. It has been theorized that at root, humanity's existential despair comes from our larger cognitive capacity. Our brains have evolved as sense-making machines. And yet, when faced with senseless tragedy, we are at a loss. Our brain is a hammer looking for a nail, and unfortunately one does not exist.

Or does it? In our quest to make sense of the world, we have invented powerful mythologies with the ultimate goal of finding purpose where there seems to be none. It is a highly useful story to tell, yet everyone knows all but one are wrong - Atheists simply claim that one is wrong too.

But what if we had a story to tell about purpose that didn't require the supernatural. Is there not enough to live for here on earth? Is there not enough to get us through the tragedies, the hardships, to inspire us with ambition, to want to make the world a better place?

When I look into the eyes of the woman I love, I feel a purpose. When I laugh along with my two daughters, I feel purpose. When my family and friends remind me of our shared memories, I feel a purpose. When I see my smiling neighbor walking past my house everyday after returning from the bustop after work, I feel purpose. When I pull weeds in my garden I feel purpose. When I finish writing a new song with my guitar I feel a purpose. When I listen to a new record that inspires me to go back and write again, I feel purpose. The roadrunner that struts across my garden wall gives me a sense of purpose. The way the tendrils of the grapevine reach out in slow motion for a new handhold, I feel purpose.

Of course, I will forget all of these things. I will become overwhelmed. I will allow negative thoughts to creep over my consciousness and push away all of the good things in my life. But time will pass, and I will overcome. I will be reminded of all of these things that give me purpose, and I will embrace them. I will have faith in their ability to change my life. I will have faith that they do indeed exist, that I will come to feel their effects again. These things are real. They exist in the natural word. I can touch them. I can make real connections with them. I have faith in these things, and through them, I have faith in Atheism.

That is, having faith in God to pull you through. Having faith that there is a plan for you, having faith that there is a meaning in the universe and a reason for everything.

Of course, no one is without doubt. Even the most devout believers must at times struggle to hold on to their faith. But they have a faith to hold on to. They have a deep and enduring story that, at least in theory, accounts for everything in their lives. It tells of a universe designed with them in mind, with special details and guarantees that promise not only an ultimate reward in the afterlife, but a better life now. It spins tragedy into harmony, grief into glory, pain into love. There may not be any specific answer to specific problems, but in faith it is promised that a deeper purpose exists, and faith will carry one through.

Unfortunately, I have no such reassurances. As an Atheist, I have no reason to believe that there is any higher purpose to my life. The universe was not designed with me in mind. It simply exists, according to a relatively limited set of physical laws. These laws have set in motion an unbelievably vast and complex series of interactions, my body and mind composed of elements forged in the ebb and flow of stellar supernovae, brought together by interactions of gravity and electromagnetics, propelled by energies as distant as the Milky Way galaxy within which our Sun orbits, and as close as the very bonds that hold my sub-atomic particles together. Within this vast cosmic dance, I do my thing.

So, what is "my thing", and more importantly, why do I do it? A question for the ages, right? What is the meaning of life? What is the purpose of life? Having already declared my Atheism, I have already submitted that there is no purpose.

Seven years ago, I tried to kill myself by overdosing on prescription pills. For twenty five years I have gone about my daily life in varying degrees of chronic pain. Sometimes it feels like the walls are closing in all around me. It is all I can do to focus my mental powers like invisible rods and struts, holding back the vice grip of gnawing muscle tension. At other times the pain is barely noticeable, lurking in the background but easily ignored. My life has been torn apart; who knows how it could have been had I not had that surfboard accident in 1989.

In my darkest moments - which thankfully, are much further far and in-between than they used to be before the suicide came as somewhat of a watershed - I do not have God to comfort me. My footsteps are my own. I cannot bend my knee and take solace in a faith that there is a purpose to my pain. There is no "lesson" that I am to learn. There were no sins that I am paying for now, redeemable for a ticket into heaven when I die. There is only the cold machinery of the universe, of which I have been on the receiving end of misfortune.

It is true that we all need purpose. I know as well as anyone what it feels like to reach the end of the tether which attaches me to my will to live. We need a reason to live. We need a reason to push on despite horrible pain, anguish and tragedy. We cannot live without purpose. Purpose is what gives our lives beauty and reminds us in moments of challenge that there is much to be thankful for. Purpose is what drives us to be better, more honest, more caring, more supportive people, to do better things, to set ambitious goals and struggle to accomplish them. Without purpose, our lives become aimless and superficial, stumbling over minor obstacles and sidetracking us towards short-term satisfactions.

If there is no God, or supernatural story within which our lives are fixed, which gives ultimate purpose to our lives, carrying us through the pain and propelling us towards the fulfillment of our best natures, how is it that the Atheist is not destined for all that accompanies a life devoid of purpose?

Some might take solace in the notion that it is Atheism itself which destroys purpose. After all, how can one ever prove that there is no God, or supernatural force that guides our destiny? Partly a semantic issue, Atheism is not incompatible with such agnosticism. It can as easily be said that one can never really prove a negative. Two plus two may equal four this time, but no one can know the future. Just because there is no evidence for God at all, and an inexhaustible supply of evidence for causal mechanisms in the natural world that need no creator to be explained. Aside from the creation of natural laws themselves, we have every reason to believe they are enough in and of themselves to explain everything that exists in the universe. Agnosticism should be the basis not only for supernatural questions, but our stance towards reality itself. However, it is merely a baseline. Acting with purpose requires so much more. While nothing may be able to be completely disproven, we live in a practical world and Occam's Razor requires us to make practical decisions. I may not know that two plus two will always equal four, but I can't sit around waiting to find out. There is just as little purpose in agnosticism as there is in Atheism.

While Atheism can give us no purpose, it makes a stronger statement about purpose in general: that we make our own purpose. In fact, in Atheism we see that all religious faiths (all but one of them being untrue, by default) are in fact man-made. Therefore, the purpose that they purport to offer the faithful is man-made as well.

Unfortunately, as a non-believing Atheist, I cannot simply adopt the purpose of the faithful as my own. And thus I cannot collect the rewards - the comfort, the inspiration. And so I must find my own. Limited to the natural world, I cannot simply invent convenient stories, hiding away in the mysticism that "everything happens for a reason", knowing full well that it doesn't. We offer no such hubris to the billions of animals that die of starvation or predation each year in the wild. The reason? That's life.

But maybe the stoicism of the natural world offers us a clue in how to make sense of a harsh reality. It has been theorized that at root, humanity's existential despair comes from our larger cognitive capacity. Our brains have evolved as sense-making machines. And yet, when faced with senseless tragedy, we are at a loss. Our brain is a hammer looking for a nail, and unfortunately one does not exist.

Or does it? In our quest to make sense of the world, we have invented powerful mythologies with the ultimate goal of finding purpose where there seems to be none. It is a highly useful story to tell, yet everyone knows all but one are wrong - Atheists simply claim that one is wrong too.

But what if we had a story to tell about purpose that didn't require the supernatural. Is there not enough to live for here on earth? Is there not enough to get us through the tragedies, the hardships, to inspire us with ambition, to want to make the world a better place?

When I look into the eyes of the woman I love, I feel a purpose. When I laugh along with my two daughters, I feel purpose. When my family and friends remind me of our shared memories, I feel a purpose. When I see my smiling neighbor walking past my house everyday after returning from the bustop after work, I feel purpose. When I pull weeds in my garden I feel purpose. When I finish writing a new song with my guitar I feel a purpose. When I listen to a new record that inspires me to go back and write again, I feel purpose. The roadrunner that struts across my garden wall gives me a sense of purpose. The way the tendrils of the grapevine reach out in slow motion for a new handhold, I feel purpose.

Of course, I will forget all of these things. I will become overwhelmed. I will allow negative thoughts to creep over my consciousness and push away all of the good things in my life. But time will pass, and I will overcome. I will be reminded of all of these things that give me purpose, and I will embrace them. I will have faith in their ability to change my life. I will have faith that they do indeed exist, that I will come to feel their effects again. These things are real. They exist in the natural word. I can touch them. I can make real connections with them. I have faith in these things, and through them, I have faith in Atheism.

Saturday, November 17, 2012

Homophobia is Irrelevant

After the recent election, it is increasingly clear that America has reached a tipping point in its acceptance of homosexuality as something natural, normal, healthy and acceptable. Voters in Maine and Maryland approved same-sex marriage, and in Wisconsin the first openly gay US senator was elected. Of course, the country remains divided, with gay acceptance being very limited among certain groups, especially in the Southern states. But looking back over the last two decades, the progress of the gay rights movement has been rather stunning.

Gay rights is commonly compared with the anti-racist civil rights movement, which has now reached the point where it is entirely socially unacceptable to advocate against the equal treatment of ethnic and racial groups. On its face, the similarities are obvious: an historically discriminated against minority group, subjected to irrational, unscientific hostility by a majority group whose main argument rests simply in an appeal to tradition. Like blacks, gays have routinely been terrorized, ostracized, oppressed, discriminated against both informally and in law. Pseudo-scientific theories have been invented to justify bigotry.

Yet proponents of discrimination against gays still cling to one key difference between gay rights and civil rights based on gender or race. While interpretations of religious text have for centuries been used to justify the oppression of women and minorities, viewing them as deserving status second-class citizens, they have largely been abandoned as backward and misguided. This owes in large part to the paucity of clear references in religious texts to the subordination of these groups. While with some work, cases can be made for interpretations that support bigoted views, modern progressive opinion, at least in the West, has largely abandoned such explicit justification. Discrimination surely still exists, as minority and female representation in positions of power is still limited. However, defense of this status quo rarely appeals to religious text, instead preferring the subtleties of other cultural traditions or social norms.

With homosexuality, things are quite different. Religious texts still stand as the primary justification for viewing homosexuals as second-class citizens. The reason for this is clear. Religious texts, especially the Old Testament, very clearly condemns homosexuality as specifically immoral and unnatural. Combined with centuries of unquestioned cultural norms of anti-gay discrimination, the verses seem clear as day. While many other practices are explicitly prescribed in religious texts that would be seen as beyond the pale (at least in most societies), their practice ended so long ago that it is easy to think of them as antiquated and retrograde.

So it may go with interpretations of religious texts that explicitly view homosexuality as sinful. However, especially in light of the passion with which so many conservative religious groups seem to have invested themselves in the condemnation of homosexuality not only as an individual sin, but the acceptance of which is emblematic of a larger social and cultural decline word-wide, religious-based opposition to homosexuality seems especially intransigent.

It is undeniable that there has always been a component of hatred to the tradition of anti-gay cultural norms. Anti-black, or anti-female sentiment has always been expressed not only in codified discrimination, but in literal violence against those groups, whether through rape or lynchings. History is replete with justifications of bigotry generally rooted in nothing more profound than simple feelings of disgust at some innate quality of women or blacks. This disgust is a feeling that becomes so powerful that it gives rise to outward expressions of discrimination or even physical violence.

However, the interesting question is where this feeling has come from. It certainly isn't something innate. Rather, it is a social construction. While there is good reason to believe that as a species, we have a tendency towards a fear of the "other" in cultural relations, there is also plenty of evidence that through social construction, we can overcome this fear by mitigating it with patterns of cultural conduct that both pre-emptively inhibit what may be perfectly natural, yet irrational dispositions towards xenophobia and the fear of the unknown. Further, we can establish norms of social and self-reflection that seek to provide a continual "check" on current social norms, ensuring that they are rational, moral and just. Looking over the centuries, it isn't hard to see an arc of moral progress in which old social norms have died away, and been replaced by enlightened perspectives. As such, old "disgusts" that we may have felt in prior centuries past - say, at seeing a woman bathing in a two piece swimsuit or driving a car, a child arguing with a parent, a black man kissing a white woman - would be hard to imagine today. Their social context has changed, and the construction of assumptions and expectations has been altered in such a way that disgust has been de-activated.

Yet in churches and radio stations across the country, the social construction of homosexuality as immoral and sinful is being activated on a regular basis. While at the same time it is being deconstructed by a continuous march of reality - one in which homosexuals engage in public activity no differently, and with no different effects than heterosexuals - there exist wide swaths of society that refuse to acknowledge its benevolence.

With feminism and minority rights, there was less for the religiously conservative to lose. Little in religious texts explicitly calls them inherently sinful. Religious interpretations that called for the subjugation of women and minorities could be slowly forgotten, or at least, as in the case of women, re-imagined in more benign terms - in rhetoric women could indeed be powerful, however the more enlightened among them would make an honest attempt to stick closer to home and define themselves within the context of traditional marriage. Having a female or black president wasn't necessarily a threat to civilization as we know it, as long as the general order of patriarchal and Christian supremacy was assumed. The union of man and woman, under God producing the next generation of Christian youth was intact.

But homosexuality undermines this vision. Not only do religious texts repeatedly describe homosexuality as outright unholy, but as a social norm, it calls into question the larger holy alliance of male and female procreation under God. This institutional construction is seen as at the very core of the faith itself. Breaking it would call into question the fundamental purpose of life on Earth, under God's plan. The implications extend far beyond homosexuality: sex-before-marriage, a woman's place in the home, a parent's relationship with his child, traditional gender roles - all of these are possibly under threat. Nothing less than a total realignment could possibly be in store if one were to go down the road towards accepting homosexuality as something neither sinful nor immoral. As Maggie Gallagher, prominent conservative critic of gay marriage, wrote apocalyptically after the recent election, "The Obama electorate defeated marriage." Gays didn't win marriage. Heterosexuals lost it - the entire institution

a

This is not to say that a massive shift cannot occur. History is filled with examples of religious interpretation shifting alongside social changes. Plenty of religious people today have found ways to reconcile an understanding of homosexuality as something perfectly natural with their faith. But unlike gender and racial equality, homosexuality is going to cause much more soul-searching.

In the meantime, there will be a debate as to whether religious intransigence represents mere principled devotion to faith, or a post-hoc religious justification for homophobic bigotry. This is a question that is impossible to answer clearly. We just don't have the opportunity to peer into the mind of our fellow man with the resolution required to determine from where his convictions arise. Without a textual case to be made, when anti-gay feelings are expressed, there is little to explain them other than simple homophobic disgust. Yet religious texts, by definition, are powerful sources of ideological guidance.

The original purpose of gender and racial equality arose not from rational, doctrinal interpretation, but from the supremely personal, human experience of inequality and injustice. This was the only truth that mattered - that which was real and felt in the minds and hearts of millions. Despite religious prevarication, so the truth of gay rights lies not in the words on any printed page, but rather in the lived experience of millions. The only question, in the end, is whether or not to trust in the loving bonds we cannot help but feel for our fellow man. When asked, in an honest, deliberate comparison of our feelings of hateful disgust versus our capacity for empathy, empathy will win out, especially in the context of widespread social pressure. However, the attempt must be made, either forced by social pressure or otherwise. Will the tide of gay acceptance reach the church walls, overwhelming calculation and fear with love and truth? Or will polarization drive the walls ever higher? My guess is, eventually, the former. But given the implications - real or perceived - for religious conservatism's driving against the liberalism it sees homosexuality as representing, the road will be a long one.

Gay rights is commonly compared with the anti-racist civil rights movement, which has now reached the point where it is entirely socially unacceptable to advocate against the equal treatment of ethnic and racial groups. On its face, the similarities are obvious: an historically discriminated against minority group, subjected to irrational, unscientific hostility by a majority group whose main argument rests simply in an appeal to tradition. Like blacks, gays have routinely been terrorized, ostracized, oppressed, discriminated against both informally and in law. Pseudo-scientific theories have been invented to justify bigotry.

Yet proponents of discrimination against gays still cling to one key difference between gay rights and civil rights based on gender or race. While interpretations of religious text have for centuries been used to justify the oppression of women and minorities, viewing them as deserving status second-class citizens, they have largely been abandoned as backward and misguided. This owes in large part to the paucity of clear references in religious texts to the subordination of these groups. While with some work, cases can be made for interpretations that support bigoted views, modern progressive opinion, at least in the West, has largely abandoned such explicit justification. Discrimination surely still exists, as minority and female representation in positions of power is still limited. However, defense of this status quo rarely appeals to religious text, instead preferring the subtleties of other cultural traditions or social norms.

With homosexuality, things are quite different. Religious texts still stand as the primary justification for viewing homosexuals as second-class citizens. The reason for this is clear. Religious texts, especially the Old Testament, very clearly condemns homosexuality as specifically immoral and unnatural. Combined with centuries of unquestioned cultural norms of anti-gay discrimination, the verses seem clear as day. While many other practices are explicitly prescribed in religious texts that would be seen as beyond the pale (at least in most societies), their practice ended so long ago that it is easy to think of them as antiquated and retrograde.

So it may go with interpretations of religious texts that explicitly view homosexuality as sinful. However, especially in light of the passion with which so many conservative religious groups seem to have invested themselves in the condemnation of homosexuality not only as an individual sin, but the acceptance of which is emblematic of a larger social and cultural decline word-wide, religious-based opposition to homosexuality seems especially intransigent.

It is undeniable that there has always been a component of hatred to the tradition of anti-gay cultural norms. Anti-black, or anti-female sentiment has always been expressed not only in codified discrimination, but in literal violence against those groups, whether through rape or lynchings. History is replete with justifications of bigotry generally rooted in nothing more profound than simple feelings of disgust at some innate quality of women or blacks. This disgust is a feeling that becomes so powerful that it gives rise to outward expressions of discrimination or even physical violence.

However, the interesting question is where this feeling has come from. It certainly isn't something innate. Rather, it is a social construction. While there is good reason to believe that as a species, we have a tendency towards a fear of the "other" in cultural relations, there is also plenty of evidence that through social construction, we can overcome this fear by mitigating it with patterns of cultural conduct that both pre-emptively inhibit what may be perfectly natural, yet irrational dispositions towards xenophobia and the fear of the unknown. Further, we can establish norms of social and self-reflection that seek to provide a continual "check" on current social norms, ensuring that they are rational, moral and just. Looking over the centuries, it isn't hard to see an arc of moral progress in which old social norms have died away, and been replaced by enlightened perspectives. As such, old "disgusts" that we may have felt in prior centuries past - say, at seeing a woman bathing in a two piece swimsuit or driving a car, a child arguing with a parent, a black man kissing a white woman - would be hard to imagine today. Their social context has changed, and the construction of assumptions and expectations has been altered in such a way that disgust has been de-activated.

Yet in churches and radio stations across the country, the social construction of homosexuality as immoral and sinful is being activated on a regular basis. While at the same time it is being deconstructed by a continuous march of reality - one in which homosexuals engage in public activity no differently, and with no different effects than heterosexuals - there exist wide swaths of society that refuse to acknowledge its benevolence.

With feminism and minority rights, there was less for the religiously conservative to lose. Little in religious texts explicitly calls them inherently sinful. Religious interpretations that called for the subjugation of women and minorities could be slowly forgotten, or at least, as in the case of women, re-imagined in more benign terms - in rhetoric women could indeed be powerful, however the more enlightened among them would make an honest attempt to stick closer to home and define themselves within the context of traditional marriage. Having a female or black president wasn't necessarily a threat to civilization as we know it, as long as the general order of patriarchal and Christian supremacy was assumed. The union of man and woman, under God producing the next generation of Christian youth was intact.

But homosexuality undermines this vision. Not only do religious texts repeatedly describe homosexuality as outright unholy, but as a social norm, it calls into question the larger holy alliance of male and female procreation under God. This institutional construction is seen as at the very core of the faith itself. Breaking it would call into question the fundamental purpose of life on Earth, under God's plan. The implications extend far beyond homosexuality: sex-before-marriage, a woman's place in the home, a parent's relationship with his child, traditional gender roles - all of these are possibly under threat. Nothing less than a total realignment could possibly be in store if one were to go down the road towards accepting homosexuality as something neither sinful nor immoral. As Maggie Gallagher, prominent conservative critic of gay marriage, wrote apocalyptically after the recent election, "The Obama electorate defeated marriage." Gays didn't win marriage. Heterosexuals lost it - the entire institution

a

This is not to say that a massive shift cannot occur. History is filled with examples of religious interpretation shifting alongside social changes. Plenty of religious people today have found ways to reconcile an understanding of homosexuality as something perfectly natural with their faith. But unlike gender and racial equality, homosexuality is going to cause much more soul-searching.

In the meantime, there will be a debate as to whether religious intransigence represents mere principled devotion to faith, or a post-hoc religious justification for homophobic bigotry. This is a question that is impossible to answer clearly. We just don't have the opportunity to peer into the mind of our fellow man with the resolution required to determine from where his convictions arise. Without a textual case to be made, when anti-gay feelings are expressed, there is little to explain them other than simple homophobic disgust. Yet religious texts, by definition, are powerful sources of ideological guidance.

The original purpose of gender and racial equality arose not from rational, doctrinal interpretation, but from the supremely personal, human experience of inequality and injustice. This was the only truth that mattered - that which was real and felt in the minds and hearts of millions. Despite religious prevarication, so the truth of gay rights lies not in the words on any printed page, but rather in the lived experience of millions. The only question, in the end, is whether or not to trust in the loving bonds we cannot help but feel for our fellow man. When asked, in an honest, deliberate comparison of our feelings of hateful disgust versus our capacity for empathy, empathy will win out, especially in the context of widespread social pressure. However, the attempt must be made, either forced by social pressure or otherwise. Will the tide of gay acceptance reach the church walls, overwhelming calculation and fear with love and truth? Or will polarization drive the walls ever higher? My guess is, eventually, the former. But given the implications - real or perceived - for religious conservatism's driving against the liberalism it sees homosexuality as representing, the road will be a long one.

Sunday, November 4, 2012

Pinning Down Will

A big problem in discussions of free will is language. One of the sticking points is often the way we talk about the meaning of will, or volition. The common intuition that we all have free will is based on the observation that most choices we make are in the context of there being many possible options. I could have eggs for breakfast, but I could also choose to do an endless number of other things. I have the freedom to decide which.

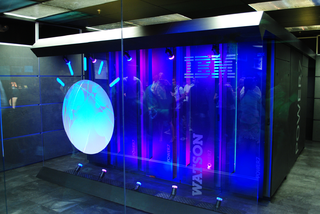

In explaining how a computer works, it would make sense to say the computer "chooses" from a set of variables, according to a predetermined set of parameters. When IBM's Watson computer famously competed and won against Jeopardy's best contestants, his responses were accompanied by the relative probabilities his system gave alternate responses. Did Watson have the "freedom" to make other responses? No, he did not. He chose the response that made the most "sense" to him, based on predetermined parameters.

I think it is important to describe will as the act of merely choosing between competing options. In doing so, we make the notion of freedom irrelevant, instead describing the fact that choices are dependent upon predetermined parameters, ultimately arising from impulses outside of, and prior to, our conscious awareness. Just as no one would describe Watson's decisions as anything like "free", no one should describe our choices as such either. The only difference is that our impulses are infinitely more complex and (presently) unknowable.

Yet to the degree that those impulses are knowable, they are deterministic. That is, when analyzing why we make any particular choice, wherever we look we see a will that is dependent on predetermined parameters.

In explaining how a computer works, it would make sense to say the computer "chooses" from a set of variables, according to a predetermined set of parameters. When IBM's Watson computer famously competed and won against Jeopardy's best contestants, his responses were accompanied by the relative probabilities his system gave alternate responses. Did Watson have the "freedom" to make other responses? No, he did not. He chose the response that made the most "sense" to him, based on predetermined parameters.

I think it is important to describe will as the act of merely choosing between competing options. In doing so, we make the notion of freedom irrelevant, instead describing the fact that choices are dependent upon predetermined parameters, ultimately arising from impulses outside of, and prior to, our conscious awareness. Just as no one would describe Watson's decisions as anything like "free", no one should describe our choices as such either. The only difference is that our impulses are infinitely more complex and (presently) unknowable.

Yet to the degree that those impulses are knowable, they are deterministic. That is, when analyzing why we make any particular choice, wherever we look we see a will that is dependent on predetermined parameters.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)