The economist has an interview up with Diane Ravitch in which she continues to promote her critiques of NCLB and the so-called education reform now popular. Some good commentary follows the piece. However I have a problem with a few of the premises being assumed (as well the larger educational ideologies they belong to).

The first is that schools are getting considerably worse across the board. When we talk about "failing schools" in the US, we are really talking about schools in demographic areas of low socio-economic status. There's an excellent site called School Performance Maps that uses Google maps to show relative test scores in cities across America. Unsurprisingly, educational quality fits poverty rates like a glove.

The second assumption I have a problem with is the emphasis on teacher quality. While some teachers are indeed good and others bad, it is a complex issue. For starters, judging performance is not cut and dry. Test scores, while useful on a large scale, are notoriously unreliable as small-scale performance indicators, owing to such things as student motivation on test-day, classroom population variance, and a particular subject's testability (can you compare a science teacher's results to an English teacher's?). To get a better view of the value of a test, you have to look at multiple schools, which for demographic and other reasons only complicate the variables.

Performance is also often evaluated by an administrator who has no experience in that subject area, or teaching in general, and often bases his or her evaluation on mere minutes spent in a single classroom. As Ravitch notes, the subjective nature of teaching is one of the reasons teachers unions are very protective of tenure (and it should more accurately be described as a system of comprehensive due process, as I've never heard of a school where tenure over-rides a due process model for termination). This is not even getting into issues of pedagogical disagreement or possible capricious firings.

Another premise, albeit an unspoken one, is the lack of accounting for school location. This is what parents talk about when they say "good schools", and it generally refers to the student population demographic. Two schools, often in the same district, can have very different test scores. The number one predictor of success is parent education, followed by income. But other issues play a role as well, mainly having to do with a family's ability to promote their child's academic success. Even with low socio-economic groups, this varies considerably, owing to such things as work schedule, substance abuse or criminality (fathers are often incarcerated), English language skills and simple efficacy in parenting or dealing with school personnel. Charter schools have frequently been able to capitalize on limiting one or more of these factors, as Ravitch mentioned. Even something as simple as not being equipped to handle students with special needs can free up resources that provide an advantage in other areas.

All of this goes to the question of teacher quality. Even if we were able to develop a reliable and scalable measure of teacher performance, we would still face the problem that teaching is a very different job in different communities. In disadvantaged populations, getting students from point A to point B is just inherently more difficult than in populations where students are much more prepared. Therefore we cannot expect the same level of results. In most poor schools, majorities of students are grade levels behind in reading ability. How much more difficult does this make the teacher's job in every subject?

These are not excuses for failure. They are reasons. It is simply foolish to base models for efficacy upon faulty frameworks. If we want poor children to succeed at the level of their advantaged peers, we as a society need to understand that we need a different model for how to get there. We need to start by targeting each area of disadvantage and developing reasonable policy that takes difference into account what might be required to achieve success. The model for schools in poor neighborhoods should be very different than that of middle class schools.

Different populations have different needs. I think the main take-away from NCLB, aside from the obvious need for reform, is that a one-size fits all approach doesn't work. We don't approach other areas of the public sector this way (foreign policy, transportation, health care), so why should education be any different? Title I funding was a step in the right direction, but it needs to go much further if we are to ever properly address the income-achievement gap in America.

A bastard's take on human behavior, politics, religion, social justice, family, race, pain, free will, and trees

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Sunday, March 28, 2010

Epistemology and Practical Morality

Freddie De Boer has an interesting piece up on Sam Harris and the New Atheist reliance on scientific materialism to solve real-world problems. A response to Harris' turn at TED, in which he argues that science can answer moral questions, DeBoer's thesis is basically that we should always be skeptical of our own certainty because of the limitations of consciousness.

The problem lies in describing exactly what types of certainty we are talking about. Some things we can be very certain of, and others we cannot. Thus how much confidence we have in any given thing is contextual. But what matters is the epistemological tools we use to determine how much certainty there exists, and how adequate they are to the task.

For instance, I know to a high degree of certainty that if I punch my neighbor in the face, he will experience pain, as I have a high degree of experiential as well as objective data that tells me this will be so.

Yet I have very little certainty that he will mind if I knock on his door at 8am instead of 9am. People wake at various hours in the morning. However if I knock on his door at 3am I can very confident I will bother him. Very few people wake that early.

I think what worries so many about post-modernism is not when it is a serious and precise philosophical discussion of why epistemology matters, but when it is a way of thinking about the world that seeks to diminish epistemology. What this often results in is a sort of selfish fealty to whatever passion one might currently be feeling.

We find this all over the political religious, and cultural spectrum. As a liberal, I've found this frequently in discussions with conservatives. Trying to get to the root of why they believe what they believe, which somewhat by definition entails an appeal to tradition, the ultimate answer is often, "Well, I don't know". For instance, when asked about the conservative emphasis on individualism and personal responsibility, and where it might come from aside from genetic and social determinism, the answer is a simple shrug of the shoulders. Yet trillions of dollars of social policy are at stake! No matter how I try and make my case, no matter how many studies I cite or arguments I present, a simple shrug of the shoulders can wash it all away.

Now, I'm not sure what I was dealing with was a conscious invocation of post-modernism. But I was certainly dealing with an argument that gets much of its strength from a social tradition that encourages the embrace of appeals to emotion rather than reason. The tradition is obviously old - vastly more so than our traditions of science and reason. The most obvious reason for this is that the epistomological tools of science and reason were not readily available. Yet to the extent that they now are, I see no reason why we should be afraid to use them.

Now, how much confidence we have in our ability to use science and reason to get at truth will always vary. Experience also tells us that we overestimate its authority at our peril. But this is at least as true as when we underestimate it. The dangers of relying on things other than science and reason are far greater.

Yet while compromise is in order, the trick is in knowing what we know, and where to place our confidence. Science has an excellent mechanism for doing this in the most objective and efficient way: consensus. Due to the degree of complexity and specialization involved in scientific progress, professional consensus is integral to the scientific process. Were any inaccuracies allowed to corrupt the process, they could not linger long for subsequent results would be unrepeatable. In this way, scientific progress itself demands a high level of objective honesty. Consensus of course, can always be wrong. But not for very long, and it is no more susceptible to error than nonscientific reasoning.

What matters in all of this is context. Scientific reasoning is not a dogmatic belief that science will always provide the answers we seek - but rather that scientific results should be taken very seriously, and should at a very minimum be held as the gold standard in knowing truth. This does not mean that results are not open to interpretation, and that scientific inquiry can't be used to draw incorrect inferences. But we should not be afraid to embrace scientific results that add to our sum of knowledge, especially when they appear to contradict our prior assumptions.

More and more, it has become the case that expert opinion must be relied upon to make judgments on important issues. Post-modernism, while a bright reminder to always remain skeptical of our sources of knowledge, must not in skepticism of things he isn't comfortable knowing allow man to substitute his own lack of knowledge for the combined wisdom of his much more able peers. This is a difficult and humbling place to find one's self in to be sure. But we can no longer conceive of ourselves as geocentric arbiters of all that is true. Instead we must seek to strengthen those institutions of society - be they government or academic - that ensure that the expertise is not only broad and robust, but accountable and self-critical. For it will be these institutions that we entrust with our continuing knowledge.

I've always felt that the kind of skepticism that is most valuable, that is to our pragmatic benefit, is the skepticism that begins the skeptical enterprise at the human mind, the classical Greek skepticism that regarded any real certainty as dogmatism. Not because it is true, or even because it is superior, but because epistemological modesty seems to me to be an entirely under appreciated tool for the practical prosecution of our lives and our arguments.That's true as far as it goes. But it is also untrue as far as it goes. The main problem I have with the essay is that without examples with which to work, it is difficult to agree or disagree with any of it.

The problem lies in describing exactly what types of certainty we are talking about. Some things we can be very certain of, and others we cannot. Thus how much confidence we have in any given thing is contextual. But what matters is the epistemological tools we use to determine how much certainty there exists, and how adequate they are to the task.

For instance, I know to a high degree of certainty that if I punch my neighbor in the face, he will experience pain, as I have a high degree of experiential as well as objective data that tells me this will be so.

Yet I have very little certainty that he will mind if I knock on his door at 8am instead of 9am. People wake at various hours in the morning. However if I knock on his door at 3am I can very confident I will bother him. Very few people wake that early.

I think what worries so many about post-modernism is not when it is a serious and precise philosophical discussion of why epistemology matters, but when it is a way of thinking about the world that seeks to diminish epistemology. What this often results in is a sort of selfish fealty to whatever passion one might currently be feeling.

We find this all over the political religious, and cultural spectrum. As a liberal, I've found this frequently in discussions with conservatives. Trying to get to the root of why they believe what they believe, which somewhat by definition entails an appeal to tradition, the ultimate answer is often, "Well, I don't know". For instance, when asked about the conservative emphasis on individualism and personal responsibility, and where it might come from aside from genetic and social determinism, the answer is a simple shrug of the shoulders. Yet trillions of dollars of social policy are at stake! No matter how I try and make my case, no matter how many studies I cite or arguments I present, a simple shrug of the shoulders can wash it all away.

Now, I'm not sure what I was dealing with was a conscious invocation of post-modernism. But I was certainly dealing with an argument that gets much of its strength from a social tradition that encourages the embrace of appeals to emotion rather than reason. The tradition is obviously old - vastly more so than our traditions of science and reason. The most obvious reason for this is that the epistomological tools of science and reason were not readily available. Yet to the extent that they now are, I see no reason why we should be afraid to use them.

Now, how much confidence we have in our ability to use science and reason to get at truth will always vary. Experience also tells us that we overestimate its authority at our peril. But this is at least as true as when we underestimate it. The dangers of relying on things other than science and reason are far greater.

Yet while compromise is in order, the trick is in knowing what we know, and where to place our confidence. Science has an excellent mechanism for doing this in the most objective and efficient way: consensus. Due to the degree of complexity and specialization involved in scientific progress, professional consensus is integral to the scientific process. Were any inaccuracies allowed to corrupt the process, they could not linger long for subsequent results would be unrepeatable. In this way, scientific progress itself demands a high level of objective honesty. Consensus of course, can always be wrong. But not for very long, and it is no more susceptible to error than nonscientific reasoning.

What matters in all of this is context. Scientific reasoning is not a dogmatic belief that science will always provide the answers we seek - but rather that scientific results should be taken very seriously, and should at a very minimum be held as the gold standard in knowing truth. This does not mean that results are not open to interpretation, and that scientific inquiry can't be used to draw incorrect inferences. But we should not be afraid to embrace scientific results that add to our sum of knowledge, especially when they appear to contradict our prior assumptions.

More and more, it has become the case that expert opinion must be relied upon to make judgments on important issues. Post-modernism, while a bright reminder to always remain skeptical of our sources of knowledge, must not in skepticism of things he isn't comfortable knowing allow man to substitute his own lack of knowledge for the combined wisdom of his much more able peers. This is a difficult and humbling place to find one's self in to be sure. But we can no longer conceive of ourselves as geocentric arbiters of all that is true. Instead we must seek to strengthen those institutions of society - be they government or academic - that ensure that the expertise is not only broad and robust, but accountable and self-critical. For it will be these institutions that we entrust with our continuing knowledge.

Saturday, March 27, 2010

Social Determinism Isn't Conservative

One of Stephen Colbert's favorite phrases is "I don't see color". This is meant to satirize modern conservatism's absolute denial of racial thinking - even as profound racial inequality continues to persist, and the movement as a whole seems obsessed with racial thinking.

One of the problems in talking about race is that minor gaffes can be blown out of proportion - witness the Gates kerfuffle. A line can be drawn between larger socio-economic structural problems and the growing pains of a cultural grappling with historical racism that emphasizes individual conflict resolution.

Those are certainly two different things. But that doesn’t mean they are entirely separate. I think it is right to emphasize that many whites are trying not to be racist, and “trivial slights” should not be mistaken for active pathology.

But racism is obviously a complex psychological phenomenon. People are certainly capable of identifying as non-racist, and on an individual level treating everyone as an equal, yet still holding unconscious racial biases.

One would hope that that social programs should live or die by their efficacy. Those in opposition to them often argue that even if they agreed with them in principle, the government is simply inadequate to run them effectively. That is a principled, if flawed argument. Government may be the worst delivery system, but it is better at guaranteeing access than any others. (Public schooling is a good example of this: private markets simply have no incentive to provide social programs).

Yet as I argued previously, conservatism is a political philosophy that can push one into viewing some racial groups as superior to others. Even to themselves they will not admit to these feelings, because racism is so taboo, but how else to explain the reality of racial social inequality, if social determinism is not evoked? They actively oppose social programs on the basis that all people can choose success, but in light of the fact that racial disparities exist, what is the other explanation except genes?

As I said though, it’s very schizophrenic. These people do not identify as racist – in fact they hate racists. And yet when they spout racist rhetoric online, at tea parties (or in the halls of congress), they somehow manage to separate it from what they believe is actual racism. The lazy welfare queens, gangbangers and “illegals” are simply individual exceptions to their race (which although fit into historical racist stereotypes, the conservatives likely were never aware of them to begin with – “Watermelon are just fruit”).

Yet the underlying driver is always the underlying conservative political worldview which is in fundamental opposition to social determinism.

One of the problems in talking about race is that minor gaffes can be blown out of proportion - witness the Gates kerfuffle. A line can be drawn between larger socio-economic structural problems and the growing pains of a cultural grappling with historical racism that emphasizes individual conflict resolution.

Those are certainly two different things. But that doesn’t mean they are entirely separate. I think it is right to emphasize that many whites are trying not to be racist, and “trivial slights” should not be mistaken for active pathology.

But racism is obviously a complex psychological phenomenon. People are certainly capable of identifying as non-racist, and on an individual level treating everyone as an equal, yet still holding unconscious racial biases.

One would hope that that social programs should live or die by their efficacy. Those in opposition to them often argue that even if they agreed with them in principle, the government is simply inadequate to run them effectively. That is a principled, if flawed argument. Government may be the worst delivery system, but it is better at guaranteeing access than any others. (Public schooling is a good example of this: private markets simply have no incentive to provide social programs).

Yet as I argued previously, conservatism is a political philosophy that can push one into viewing some racial groups as superior to others. Even to themselves they will not admit to these feelings, because racism is so taboo, but how else to explain the reality of racial social inequality, if social determinism is not evoked? They actively oppose social programs on the basis that all people can choose success, but in light of the fact that racial disparities exist, what is the other explanation except genes?

As I said though, it’s very schizophrenic. These people do not identify as racist – in fact they hate racists. And yet when they spout racist rhetoric online, at tea parties (or in the halls of congress), they somehow manage to separate it from what they believe is actual racism. The lazy welfare queens, gangbangers and “illegals” are simply individual exceptions to their race (which although fit into historical racist stereotypes, the conservatives likely were never aware of them to begin with – “Watermelon are just fruit”).

Yet the underlying driver is always the underlying conservative political worldview which is in fundamental opposition to social determinism.

Friday, March 26, 2010

Success and Logic of Racial Vengeance

With the tea party rhetoric and angry white right in full force, it's worth remembering that opposition to minority targeted social programs shouldn't be construed as necessarily being racist.

But I think that it is definitely the case for some people. I think that a good deal of racism actually logically follows from modern conservatism (although the deeper assumptions about human behavior are the real issue).

The basic premise is this: if everyone can succeed by getting cleaned up, getting to work on time, using their brain and moving ahead, why do minority communities have such higher rates of dysfunction? The internal logic of that statement implies that minorities must have something wrong with them that predisposes them to make poor decisions while the rest of us are able to make good ones.

The key phrase is "if everyone can succeed", which implies that we are all on a level playing field - a core assumption of modern conservatism, steeped as it is in American exceptionalism, providence and all that Neo-Christian bullshit. Thus they wave away the mountains of social research, psychology, economics, etc. as leftist propaganda because it interferes with their main premise.

Most interestingly, however, they ALL have a deep and abiding believe in contra-causal free will. On the one hand, this provides a magic antidote to the problem posed by evidence of social determinism. But on the other it would also seem to be incongruent with the obvious fact that economic disparities exist between groups. For if we all have free will, and are not determined by social forces, then one would expect to find random occurrence of levels of prosperity across groups, as no cultural forces have explanatory power.

At this point I find their logic to break down, and I can't get my mind around its incoherence. It would seem that "if everyone can succeed" but that obviously some don't, then there must be some reason why, and thus free will breaks down and either social determinism or racialism comes in.

Yet people don't really need to be rational or coherent. People are entirely capable of holding multiple contradictory positions in their head at once. My best guess is that conservative individualism meets social inequality and realizes that to survive it must place blame somewhere, but the only two options are either to embrace genetic racism or social determinism. The former entails a decades old taboo, and the latter a break-down of their philosophical premise.

So what likely happens is a sort of a cognitive parlor game in which multiple positions are held simultaneously, yet must always be ready to be backed away from or leaned into - whichever the moment requires.

The progressive, of course, is not bound by contra-causal free will, and is thus able to embrace personal responsibility as existing within a framework of social determinism. So while even if "any one can succeed", they must first need to know how, and possess the minimum level of social and human capital that success requires. Somewhat ironically, this progressive logic actually deflates the sense of frustration and desire for vengeance that might come from seeing people behaving badly, and then being forced as a society to help them out. Yet for the conservative, there is no rationalization to be found in the incoherence of contra-causal free will, and thus frustrated and vengeance is fomented - both in the direct social costs of group dysfunction, as well the resulting progressive attempts to hold the conservative accountable.

But I think that it is definitely the case for some people. I think that a good deal of racism actually logically follows from modern conservatism (although the deeper assumptions about human behavior are the real issue).

The basic premise is this: if everyone can succeed by getting cleaned up, getting to work on time, using their brain and moving ahead, why do minority communities have such higher rates of dysfunction? The internal logic of that statement implies that minorities must have something wrong with them that predisposes them to make poor decisions while the rest of us are able to make good ones.

The key phrase is "if everyone can succeed", which implies that we are all on a level playing field - a core assumption of modern conservatism, steeped as it is in American exceptionalism, providence and all that Neo-Christian bullshit. Thus they wave away the mountains of social research, psychology, economics, etc. as leftist propaganda because it interferes with their main premise.

Most interestingly, however, they ALL have a deep and abiding believe in contra-causal free will. On the one hand, this provides a magic antidote to the problem posed by evidence of social determinism. But on the other it would also seem to be incongruent with the obvious fact that economic disparities exist between groups. For if we all have free will, and are not determined by social forces, then one would expect to find random occurrence of levels of prosperity across groups, as no cultural forces have explanatory power.

At this point I find their logic to break down, and I can't get my mind around its incoherence. It would seem that "if everyone can succeed" but that obviously some don't, then there must be some reason why, and thus free will breaks down and either social determinism or racialism comes in.

Yet people don't really need to be rational or coherent. People are entirely capable of holding multiple contradictory positions in their head at once. My best guess is that conservative individualism meets social inequality and realizes that to survive it must place blame somewhere, but the only two options are either to embrace genetic racism or social determinism. The former entails a decades old taboo, and the latter a break-down of their philosophical premise.

So what likely happens is a sort of a cognitive parlor game in which multiple positions are held simultaneously, yet must always be ready to be backed away from or leaned into - whichever the moment requires.

The progressive, of course, is not bound by contra-causal free will, and is thus able to embrace personal responsibility as existing within a framework of social determinism. So while even if "any one can succeed", they must first need to know how, and possess the minimum level of social and human capital that success requires. Somewhat ironically, this progressive logic actually deflates the sense of frustration and desire for vengeance that might come from seeing people behaving badly, and then being forced as a society to help them out. Yet for the conservative, there is no rationalization to be found in the incoherence of contra-causal free will, and thus frustrated and vengeance is fomented - both in the direct social costs of group dysfunction, as well the resulting progressive attempts to hold the conservative accountable.

Thursday, March 25, 2010

NCLB Got Us Rolling

Now we need to do something about it. My main take on NCLB is that it was a way to show in a powerful and public way how many schools are failing to do what they were thought to be doing. (I specifically did not say "failing", because that word is loaded and requires unpacking: It is one thing to fail because you weren't able to do a job that you should have been able to do, it is another thing to fail to do a job it wasn't possible for you to do.)

I think most educators in relevant schools, or familiar with the data already out there for decades knew this was true, and the reasons why. But NCLB made it public, and forced the public's hand on education-as-a-right. At the same time, however, in trying to bring upwards, punitive pressure to low-performers (read mostly low-SES, across - but also within - schools), it also brought downwards pressure to high-performers, in the form of lowest-common-denominator, one-size fits all curriculum and teaching to the test, etc.

I think it's illustrative to look at the very title of the act from a philosophical point of view. "No Child Left Behind" places laser-like emphasis on those kids who had previously been glossed over. It represents a dramatic clarion call to a larger educational philosophy that is not about intervention but inspiration and a love of learning.

30 years ago, when I was in kindergarten, I'm not sure there was any pencil-paper work at all. We were given access to rich materials, encouraged to play imaginatively, learned cooperative songs and generally explored the classroom. That Kindergarten no longer exists. There is a scripted, mandated curriculum that is all about phonics, rote memorization, and discipline. The difference is that while the former model worked fine for me and my middle class peers, it was catastrophic for disadvantaged children, who lacked the social resources at home to fill out what was not explicitly taught in school. Research shows that more structured academic skill building - surprise - really improves results. But what you lose is the other side of the spectrum, where critical thinking, student-centered, collaborative and exploratory learning is thrown out, or relegated to the odd teacher who is able to actually pull it off despite the prescribed curriculum.

And so you have this clash of philosophies playing out over a range of socio-economic demographics. Inner-city parents are being pushed into hyper-structured, factory-style learning because given budgetary realities, with one teacher and 30 students (a large percentage needing intervention), that's what gives you the most bang for your buck. Meanwhile middle class parents are freaking out because the state has now mandated this model across the board, and school has become even more drudgerous (as if that were even possible).

We're just now dealing with the fallout of a massive sector of the economy that is routinely and systematically failing to do what we want it to do. Yet it is less that the schools are getting worse, we are just getting better at quantifying the achievement gaps that had always existed. We just weren't all that concerned about it. I mean, Jaime Escalante started teaching in 1974. 1974!!!

The "war on poverty" was just getting rolling. For instance, the classic study that Hart & Risley did on SES and early childhood language development wasn't even completed until into the 1980's, when A Nation at Risk came out. While in some ways that report's recommendations have yet to be fully implemented (the extension of the school day and year - being the biggest - would require considerable increases in funding), the report is laughably naive in its suggestions for correcting the real differences in SES achievement.

I think it was just a matter of the data building and building, but we've finally gotten to the point where we realize how important a quality education is. We don't have to guarantee it. I think that's a moral question masquerading as a philosophical one. But until we do, nothing will really happen. We can fiddle around and fool ourselves into thinking if we just find the right way to do what we're doing better we'll ever "leave no child behind". We might do a bit better here or there for a while. But we won't come close until we dramatically rethink what we want education to be in society, and seriously ask ourselves how important that goal really is.

(And the Flaming Lips new album, "Embryonic" is amazing...)

I think most educators in relevant schools, or familiar with the data already out there for decades knew this was true, and the reasons why. But NCLB made it public, and forced the public's hand on education-as-a-right. At the same time, however, in trying to bring upwards, punitive pressure to low-performers (read mostly low-SES, across - but also within - schools), it also brought downwards pressure to high-performers, in the form of lowest-common-denominator, one-size fits all curriculum and teaching to the test, etc.

I think it's illustrative to look at the very title of the act from a philosophical point of view. "No Child Left Behind" places laser-like emphasis on those kids who had previously been glossed over. It represents a dramatic clarion call to a larger educational philosophy that is not about intervention but inspiration and a love of learning.

30 years ago, when I was in kindergarten, I'm not sure there was any pencil-paper work at all. We were given access to rich materials, encouraged to play imaginatively, learned cooperative songs and generally explored the classroom. That Kindergarten no longer exists. There is a scripted, mandated curriculum that is all about phonics, rote memorization, and discipline. The difference is that while the former model worked fine for me and my middle class peers, it was catastrophic for disadvantaged children, who lacked the social resources at home to fill out what was not explicitly taught in school. Research shows that more structured academic skill building - surprise - really improves results. But what you lose is the other side of the spectrum, where critical thinking, student-centered, collaborative and exploratory learning is thrown out, or relegated to the odd teacher who is able to actually pull it off despite the prescribed curriculum.

And so you have this clash of philosophies playing out over a range of socio-economic demographics. Inner-city parents are being pushed into hyper-structured, factory-style learning because given budgetary realities, with one teacher and 30 students (a large percentage needing intervention), that's what gives you the most bang for your buck. Meanwhile middle class parents are freaking out because the state has now mandated this model across the board, and school has become even more drudgerous (as if that were even possible).

We're just now dealing with the fallout of a massive sector of the economy that is routinely and systematically failing to do what we want it to do. Yet it is less that the schools are getting worse, we are just getting better at quantifying the achievement gaps that had always existed. We just weren't all that concerned about it. I mean, Jaime Escalante started teaching in 1974. 1974!!!

The "war on poverty" was just getting rolling. For instance, the classic study that Hart & Risley did on SES and early childhood language development wasn't even completed until into the 1980's, when A Nation at Risk came out. While in some ways that report's recommendations have yet to be fully implemented (the extension of the school day and year - being the biggest - would require considerable increases in funding), the report is laughably naive in its suggestions for correcting the real differences in SES achievement.

I think it was just a matter of the data building and building, but we've finally gotten to the point where we realize how important a quality education is. We don't have to guarantee it. I think that's a moral question masquerading as a philosophical one. But until we do, nothing will really happen. We can fiddle around and fool ourselves into thinking if we just find the right way to do what we're doing better we'll ever "leave no child behind". We might do a bit better here or there for a while. But we won't come close until we dramatically rethink what we want education to be in society, and seriously ask ourselves how important that goal really is.

(And the Flaming Lips new album, "Embryonic" is amazing...)

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Denial in California

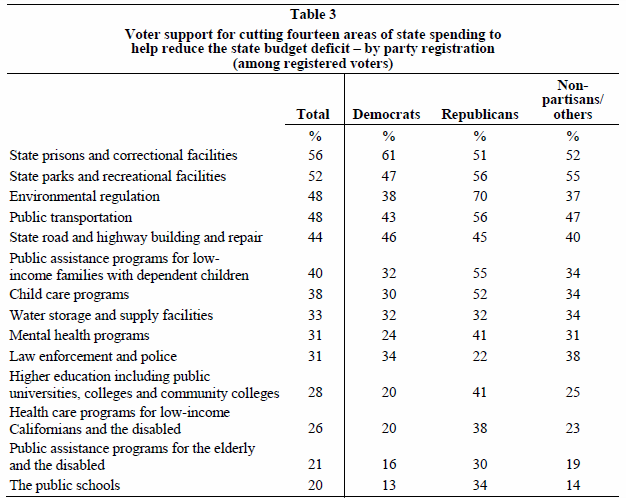

A new Field poll has come out with numbers on what kind of spending cuts Californians would like to see. It is no surprise really, but a majority of voters favor barely any cuts at all. Out of 14 categories, the only two to eke out a narrow majority of votes are parks & prisons.

More interestingly however, is how it breaks down along party lines.

Democrats unsurprisingly only agree to cut one major category

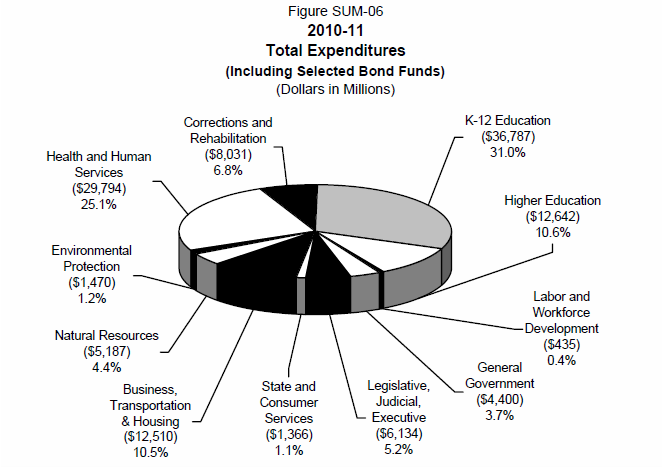

But when you look at the state budget, many of these categories represent a very slight percentage of the budget.

Obviously these sorts of attitudes aren't sustainable, for either party, without an increase in taxes. For Democrats, who would only like to see cuts in prisons, the only area of savings is going to have to come out of the prison budget, which is only around 7% of total spending. As it exists today, it is faced with a number of problems, not the least of which is overcrowding.

For the GOP, much more willing to make cuts, the overwhelmingly desired cut is to environmental regulation, which barely makes up 1% of the budget. It's about evenly tied on whether to cut prisons, parks, public transportation, and child and family services, which do take up a considerable portion of the budget.

All of which spells out pretty well why we are a state in such dire financial straits. The public is massively polarized over what types of services the government should be performing. The Democrats and GOP are locked in a bitter struggle with deep roots in very different views of human nature and social development.

But with climbing deficits, and no other option than emergency program cuts, the state is literally being forced to follow the GOP's world view of what role the government should play in a modern capitalist society - with the possible exception of prisons being forced to release convicts early. If Democrats want to see their vision of a government more actively involved in ameliorating what they view as a struggle for basic rights and equal opportunities, they must demand that Californians embrace higher levels of taxation.

More interestingly however, is how it breaks down along party lines.

Democrats unsurprisingly only agree to cut one major category

• prisons (by 61%).Also no surprise is the GOP's endorsement of cuts in

• environmental regulation (70%)Everyone agrees that the last thing to cut is education (20% all voters, 13% Democrats, 34% GOP).

• state parks and recreation (56%)

• public transportation (56%)

• public assistance programs for low-income families with dependent children (55%)

• child care programs (52%)

• state prisons and correctional facilities (51%)

But when you look at the state budget, many of these categories represent a very slight percentage of the budget.

Obviously these sorts of attitudes aren't sustainable, for either party, without an increase in taxes. For Democrats, who would only like to see cuts in prisons, the only area of savings is going to have to come out of the prison budget, which is only around 7% of total spending. As it exists today, it is faced with a number of problems, not the least of which is overcrowding.

For the GOP, much more willing to make cuts, the overwhelmingly desired cut is to environmental regulation, which barely makes up 1% of the budget. It's about evenly tied on whether to cut prisons, parks, public transportation, and child and family services, which do take up a considerable portion of the budget.

All of which spells out pretty well why we are a state in such dire financial straits. The public is massively polarized over what types of services the government should be performing. The Democrats and GOP are locked in a bitter struggle with deep roots in very different views of human nature and social development.

But with climbing deficits, and no other option than emergency program cuts, the state is literally being forced to follow the GOP's world view of what role the government should play in a modern capitalist society - with the possible exception of prisons being forced to release convicts early. If Democrats want to see their vision of a government more actively involved in ameliorating what they view as a struggle for basic rights and equal opportunities, they must demand that Californians embrace higher levels of taxation.

Labels:

california,

democrats,

government,

republicans,

taxes

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

What "Teacher Bashing" Really Means

Matt Yglesias, a true believer in the new education reform movement, isn't very interested in looking at much else than bad teaching. He offered this gem on his blog today:

I think this is very well said. To be fair, many reformers are being pragmatic, and focusing their efforts on working within the current political realities. But in doing so, they have fooled themselves into believing that the marginal gains you might get on "better teaching" from accountability/standards/charters/etc. are actually substantive.

In reality, I think they are zero-sum at best, as for every gain you get when these policies contribute to more effective education environments, you're also creating room for more impersonal curriculum, punitive and capricious administrative abuses, and a further push towards factory-style learning. These negatives will cause a downward push on talent and more good teachers leave the profession in frustration or simply decide it isn't worth entering to begin with.

Basically, you're trying to fit a square peg in a round hole. Some schools will find a way to do it by the skin of their noses, but at least as many will contort themselves into grotesque and unhealthy deformities. As soullite and Math Teacher said, the real problem isn't the teachers, but the system, which for too long has been able to hide behind the sacrifices of many of us in the profession who are there to change lives, and have been able to put up with structural inadequacies because we've had to.

Matt Y sets up a series of straw men. Accusations of "teacher bashing" aren't directed at getting effective teachers to poor kids. Who would oppose that? The claim is that the "efforts" see bad teachers as the root problem, and not structural inadequacies. And instead of fixing those (starting by accounting for enormous disparities in social capital between SES groups), the reformers blame teachers when disparities in outcome persist.

He then claims that these accusers also claim that teaching is "irrelevant to the learning process." That's a pretty sickening statement. I challenge him to find a single quote anywhere that argues that. I don't mean to do his thinking for him, but he may have meant to say that these accusers don't place enough emphasis on teacher efficacy in the learning process. Maybe that's a valid critique (I'll thank myself). But what would you expect? When the opponent is doing nothing but attacking you with overemphasized false claims, your defensiveness gives the impression that you under-emphasize them.

God... shades of arguing with batshits! Ask most teachers and they will tell you that they hate bad teachers - not only is it bad for kids, but it literally makes their job harder, and it makes them look bad. And while things like union protection and tenure do make it more difficult to get rid of them, just as often the problem is administrators who simply do not do the heavy lifting in holding them accountable. Over and over you will find that teachers are given little supervision and little support.

So the equation becomes setting them up to fail, and then not holding them accountable when they do. This story in the LA Times gives a great primer on the problem that teachers see over and over. There are ample ways for administrators to hold teachers accountable but the bottom line is that they often choose not to - whether because they are over-worked as it is, or lack the competence.

The idea has gotten out there that efforts to ensure that students from poor families have access to effective teachers is somehow a form of “teacher-bashing.” When you think about it, the reverse is true—the real teacher-bashers out there are the ones insisting, contrary to the evidence, that teaching is irrelevant to the learning process.One of his commenters takes him to task.

You’ve basically decided that doing the only thing that could actually solve this problem is too politically difficult, so you’re just going to make up a bunch of random shit for political grand standing. Shock of all shocks, you’ve chosen unions as your targets.

I think this is very well said. To be fair, many reformers are being pragmatic, and focusing their efforts on working within the current political realities. But in doing so, they have fooled themselves into believing that the marginal gains you might get on "better teaching" from accountability/standards/charters/etc. are actually substantive.

In reality, I think they are zero-sum at best, as for every gain you get when these policies contribute to more effective education environments, you're also creating room for more impersonal curriculum, punitive and capricious administrative abuses, and a further push towards factory-style learning. These negatives will cause a downward push on talent and more good teachers leave the profession in frustration or simply decide it isn't worth entering to begin with.

Basically, you're trying to fit a square peg in a round hole. Some schools will find a way to do it by the skin of their noses, but at least as many will contort themselves into grotesque and unhealthy deformities. As soullite and Math Teacher said, the real problem isn't the teachers, but the system, which for too long has been able to hide behind the sacrifices of many of us in the profession who are there to change lives, and have been able to put up with structural inadequacies because we've had to.

Matt Y sets up a series of straw men. Accusations of "teacher bashing" aren't directed at getting effective teachers to poor kids. Who would oppose that? The claim is that the "efforts" see bad teachers as the root problem, and not structural inadequacies. And instead of fixing those (starting by accounting for enormous disparities in social capital between SES groups), the reformers blame teachers when disparities in outcome persist.

He then claims that these accusers also claim that teaching is "irrelevant to the learning process." That's a pretty sickening statement. I challenge him to find a single quote anywhere that argues that. I don't mean to do his thinking for him, but he may have meant to say that these accusers don't place enough emphasis on teacher efficacy in the learning process. Maybe that's a valid critique (I'll thank myself). But what would you expect? When the opponent is doing nothing but attacking you with overemphasized false claims, your defensiveness gives the impression that you under-emphasize them.

God... shades of arguing with batshits! Ask most teachers and they will tell you that they hate bad teachers - not only is it bad for kids, but it literally makes their job harder, and it makes them look bad. And while things like union protection and tenure do make it more difficult to get rid of them, just as often the problem is administrators who simply do not do the heavy lifting in holding them accountable. Over and over you will find that teachers are given little supervision and little support.

So the equation becomes setting them up to fail, and then not holding them accountable when they do. This story in the LA Times gives a great primer on the problem that teachers see over and over. There are ample ways for administrators to hold teachers accountable but the bottom line is that they often choose not to - whether because they are over-worked as it is, or lack the competence.

Monday, March 22, 2010

Who Are We?

Judith Butler is a Maxine Elliot Professor in the Departments of Rhetoric and Comparative Literature at University of California Berkeley. In a recent interview she discusses her latest book, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable?

A fierce critic of war, or at least our seeming endless tolerance for it, she has harsh words for Obama, who she says has not nearly been the critic of war she would have liked him to be. But, as a philosopher, she's more interested in getting at deeper questions, and tries to see how we end up where we do.

I think before entering warfare one needs to ask oneself whether, if it were to take place in their own country, they would fight in the same way. If the answer is yes, then there is no moral hypocrisy. But as soon as you begin to think of the lives of inhabitants of some far off land as less meaningful than those of your countrymen, you've begun to lose your humanity.

A similar thought occurred to me today, albeit on a much different subject. We are putting an addition on our house, which is about 2 hours from the Mexican border. Many in our community are migrant workers, some legal, some not. Well, a couple of Mexicans came to my door, speaking very poor English, and offered a bid to stucco the exterior walls. I thanked them for the offer, and said I'd give their card to the contractor - who as it happens has at least one undocumented worker in his employ.

I wondered how I felt about profiting from illegal labor - certainly their wages would be a drag on those of naturalized citizens. How would I like it if an undocumented Mexican was able to compete for my job as a teacher? And what if that meant a substantial pay cut?

I'm not sure I would have a problem with it. I mean, sure, I want to get paid as much as I can. But what right do I have over anyone else, if they can the do the same job for less? What right do I have, just because the uterus I came out of 34 years ago just happened to have been a US citizen? We only need to go a handful of uteruses back and my family tree would have been the ones doing the displacement.

Nationalism, while a useful and nostalgic concept, can lead to the most base sort of inhumanity and objectification. What other tendency of human thought can be so soaked in the blood of injustice than provincial arrogance and arbitrary righteousness? Such despicable, beast-like behavior. Every man for himself, this is my lifeboat, get out. The post-hoc rationalizations fill endless volumes of rhetoric down through the centuries. They trickle slowly through the days like sticky-saccharine.

Looking back, we've come so far. But we have so far to go still.

A fierce critic of war, or at least our seeming endless tolerance for it, she has harsh words for Obama, who she says has not nearly been the critic of war she would have liked him to be. But, as a philosopher, she's more interested in getting at deeper questions, and tries to see how we end up where we do.

Along with many other people, I am trying to contest the notion that we can only value, shelter, and grieve those lives that share a common language or cultural sameness with ourselves. The point is not so much to extend our capacity for compassion, but to understand that ethical relations have to cross both cultural and geographical distance. Given that there is global interdependency in relation to the environment, food supply and distribution, and war, do we not need to understand the bonds that we have to those we do not know or have never chosen? This takes us beyond communitarianism and nationalism alike. Or so I hope.

I think before entering warfare one needs to ask oneself whether, if it were to take place in their own country, they would fight in the same way. If the answer is yes, then there is no moral hypocrisy. But as soon as you begin to think of the lives of inhabitants of some far off land as less meaningful than those of your countrymen, you've begun to lose your humanity.

A similar thought occurred to me today, albeit on a much different subject. We are putting an addition on our house, which is about 2 hours from the Mexican border. Many in our community are migrant workers, some legal, some not. Well, a couple of Mexicans came to my door, speaking very poor English, and offered a bid to stucco the exterior walls. I thanked them for the offer, and said I'd give their card to the contractor - who as it happens has at least one undocumented worker in his employ.

I wondered how I felt about profiting from illegal labor - certainly their wages would be a drag on those of naturalized citizens. How would I like it if an undocumented Mexican was able to compete for my job as a teacher? And what if that meant a substantial pay cut?

I'm not sure I would have a problem with it. I mean, sure, I want to get paid as much as I can. But what right do I have over anyone else, if they can the do the same job for less? What right do I have, just because the uterus I came out of 34 years ago just happened to have been a US citizen? We only need to go a handful of uteruses back and my family tree would have been the ones doing the displacement.

Nationalism, while a useful and nostalgic concept, can lead to the most base sort of inhumanity and objectification. What other tendency of human thought can be so soaked in the blood of injustice than provincial arrogance and arbitrary righteousness? Such despicable, beast-like behavior. Every man for himself, this is my lifeboat, get out. The post-hoc rationalizations fill endless volumes of rhetoric down through the centuries. They trickle slowly through the days like sticky-saccharine.

Looking back, we've come so far. But we have so far to go still.

Saturday, March 20, 2010

Conservatives in the Belfry

I tend to write a lot about conservatism. Lord knows I'm not one. Or at least not in any recognizably modern capacity. Yet there is a tradition among conservatism, as opposed to progressivism, that is worth remembering. It isn't about gay sex, or guns, or even capitalism. It is conservative in much the same way liberalism is progressive. It is simply a voice of reason to the excesses of progress, as liberalism is to the voice of tradition. It is a very powerful and profound political impulse, one we would be lost without. This is not the conservatism I have a problem with.

My problem is really with the current conservative base, which is batshit. The conservatism I can actually find coherence in is basically center right social democrat. The current conservatism isn't really conservative at all. It is a bastardization of that fundamentally healthy and reasonable force.

This is how I think of it: they're the new communists. The communists wanted total state, total denuding of religion. They had a marriage of convenience with the radical anticapitalist anarchosyndicalists, who so hated capitalism they'd prefer to suffer flirting with totalitarianism than more corporate oppression. They were batshit. They caused some real problems. Fortunately for those of us on the other side of history, we now have a huge, blinking neon sign that says COMMUNISM = BAD etched into history, (in the form of every communist regime that ever existed).

Modern conservatives are their doppelgangers: no state, total pro-capitalism free enterprise. They have their own marriage of convenience with Christianist theocrats, who put up with the worship of the dollar because it's better than a strong secular state telling them who they can and can't persecute. They are causing some pretty serious problems, but presently have no outlet for their utopian fantasies. All they can really do is obstruct and hope their rhetoric wins the day.

The modern problem is that because they'll never be able to get reasonable society to go along with their crazy. Their arguments enjoy an air of utopian promise - a hint that if only we just got rid of "big government" all of our problems would be solved. It's completely delusional. But it gets to maintain traction because it can always point to the possibilities. So when Republicans can't govern for shit and begin to destroy the country with all the spending none of the taxes, all they have to do is point the finger at those who just weren't true believers.

Even while people like good public schools for poor kids. People like to guarantee health care to the sick. people like a basic safety net. People like public transportation, clean libraries, mental health clinics, safety inspections, pollution regulation, parks and beaches and the notion of the common good.

Maybe we'll reach a point where the public will be forced to choose between big government and low taxes. But as long as the middle class is ignorant enough of the underclass and disadvantaged, modern conservatism can probably keep selling them on the notion that a 5% increase in taxes is big government, all the while using rhetoric that is logically more consistent with enormous cuts in all the things the middle class takes for granted. "Small government" is not quality public school for poor kids, guaranteed health coverage (not for the elderly nor infirm either), adequate regulation for safety and environmental protection, or safety net.

The communist and anarchist left has largely shut the fuck up. But what will it take to get the small government, modern conservative to do the same? My guess is nothing less than a soviet-expansion style, yet free-market small government dominance in some high-profile countries, lasting a good 2 or 3 decades. I don't think this will actually happen, because the now universally accepted rights of democracy and freedom of speech won't let any citizenry maintain the levels of insanity required to enforce such a brutal state. The only reason communism was able to persist was through its lack of democracy.

So my guess is that we will basically be plagued with this sort of adolescent Randian hand-waving that is as Utopian as it is intellectually dishonest in its denial of the incredibly large and salient amount of evidence for why it will never work. In other words it is batshit.

The communists thought that humans were perfect, and could run a productive economy. They were willing to give over massive amounts of authority to see their perfect vision realized. The modern conservatives believe that humans can be perfect if they choose to, and that markets are self-sustaining. And so they are willing to over look massive amounts of social injustice to realize theirs.

One would like to see us move on, to solve our problems like adults. We can all agree that free markets are wonderful, but that they are not self-sustaining of social equality and justice - social capital, tragedy of the commons, etc. We can all agree that government can be a wonderful check on social inequality and the capricious and inherently immoral nature of the free market. But it is also prone to corruption and inherently unwieldy and inefficient. We can agree that people can do amazing things if given the chance, but also be enslaved by dysfunctional consciousness when disadvantaged either by social structure or pure happenstance.

Adults can hold all of those truths in their heads at once and craft thoughtful, nuanced positions with respect to how we'd like to set policy for ourselves and future generations. It isn't easy, nor is it very satisfying. It takes longer to speak and think in such terms. It is much easier to traffic in generalizations infused with impulsive emotion than to be deliberately contemplative. But we can admit that we don't have everything sorted out, and then take the time to have the discussion.

My problem is really with the current conservative base, which is batshit. The conservatism I can actually find coherence in is basically center right social democrat. The current conservatism isn't really conservative at all. It is a bastardization of that fundamentally healthy and reasonable force.

This is how I think of it: they're the new communists. The communists wanted total state, total denuding of religion. They had a marriage of convenience with the radical anticapitalist anarchosyndicalists, who so hated capitalism they'd prefer to suffer flirting with totalitarianism than more corporate oppression. They were batshit. They caused some real problems. Fortunately for those of us on the other side of history, we now have a huge, blinking neon sign that says COMMUNISM = BAD etched into history, (in the form of every communist regime that ever existed).

Modern conservatives are their doppelgangers: no state, total pro-capitalism free enterprise. They have their own marriage of convenience with Christianist theocrats, who put up with the worship of the dollar because it's better than a strong secular state telling them who they can and can't persecute. They are causing some pretty serious problems, but presently have no outlet for their utopian fantasies. All they can really do is obstruct and hope their rhetoric wins the day.

The modern problem is that because they'll never be able to get reasonable society to go along with their crazy. Their arguments enjoy an air of utopian promise - a hint that if only we just got rid of "big government" all of our problems would be solved. It's completely delusional. But it gets to maintain traction because it can always point to the possibilities. So when Republicans can't govern for shit and begin to destroy the country with all the spending none of the taxes, all they have to do is point the finger at those who just weren't true believers.

Even while people like good public schools for poor kids. People like to guarantee health care to the sick. people like a basic safety net. People like public transportation, clean libraries, mental health clinics, safety inspections, pollution regulation, parks and beaches and the notion of the common good.

Maybe we'll reach a point where the public will be forced to choose between big government and low taxes. But as long as the middle class is ignorant enough of the underclass and disadvantaged, modern conservatism can probably keep selling them on the notion that a 5% increase in taxes is big government, all the while using rhetoric that is logically more consistent with enormous cuts in all the things the middle class takes for granted. "Small government" is not quality public school for poor kids, guaranteed health coverage (not for the elderly nor infirm either), adequate regulation for safety and environmental protection, or safety net.

The communist and anarchist left has largely shut the fuck up. But what will it take to get the small government, modern conservative to do the same? My guess is nothing less than a soviet-expansion style, yet free-market small government dominance in some high-profile countries, lasting a good 2 or 3 decades. I don't think this will actually happen, because the now universally accepted rights of democracy and freedom of speech won't let any citizenry maintain the levels of insanity required to enforce such a brutal state. The only reason communism was able to persist was through its lack of democracy.

So my guess is that we will basically be plagued with this sort of adolescent Randian hand-waving that is as Utopian as it is intellectually dishonest in its denial of the incredibly large and salient amount of evidence for why it will never work. In other words it is batshit.

The communists thought that humans were perfect, and could run a productive economy. They were willing to give over massive amounts of authority to see their perfect vision realized. The modern conservatives believe that humans can be perfect if they choose to, and that markets are self-sustaining. And so they are willing to over look massive amounts of social injustice to realize theirs.

One would like to see us move on, to solve our problems like adults. We can all agree that free markets are wonderful, but that they are not self-sustaining of social equality and justice - social capital, tragedy of the commons, etc. We can all agree that government can be a wonderful check on social inequality and the capricious and inherently immoral nature of the free market. But it is also prone to corruption and inherently unwieldy and inefficient. We can agree that people can do amazing things if given the chance, but also be enslaved by dysfunctional consciousness when disadvantaged either by social structure or pure happenstance.

Adults can hold all of those truths in their heads at once and craft thoughtful, nuanced positions with respect to how we'd like to set policy for ourselves and future generations. It isn't easy, nor is it very satisfying. It takes longer to speak and think in such terms. It is much easier to traffic in generalizations infused with impulsive emotion than to be deliberately contemplative. But we can admit that we don't have everything sorted out, and then take the time to have the discussion.

Friday, March 19, 2010

Calling Congress

So, with major votes coming up on HCR, representatives across the country are being inundated with calls and letters from constituents. But what good does any of it do? As technology has advanced, has it had any effect on the efficacy of calling your local congressperson? Today we have text messages, emails, website polls. We used to only have the old fashioned letter - and what did that mean to the officeholder?

This is a problem I have in general with representation. What should a representative make of calls or letters to his office? There just seems to be so much that could be inaccurate about the information. For instance, has some interest group mobilized supporters, in which case the number of calls/letters is a skewed representation.

Or does the issue have a certain appeal to a certain type of voter that might be interested more than others – for instance, a priority for a small number of voters might be 3rd or 4th on the list for the majority, and so a lack of call volume on one side doesn’t represent lack of opinion, but a reflection of how much any one citizen can be involved in every issue.

Then there is just the inherent bias in that there is a certain percent of the population that is more inclined to contact their representative. Does this make their stance any more significant, or indicative of larger sentiment?

And lastly, to what extent does rhetorical competence play a role? Does the fact that I can make a great case for issue X necessarily mean anything more than my fellow citizen who can’t? I mean, what kind of debate is taking place between the message and the congressional staffer? Especially on issues where there is a large volume of messaging, what can really be gleaned from any one constituent? I can’t imagine an aide saying, “Senator, look at this great argument here. They’re really on to something!” I’ve actually had a response from my state Senator, and I couldn’t believe it was really him who penned it. If he didn’t, what point did it serve when we weren’t really going to have a serious discussion. And if he did, doesn’t he have better things to do with his time?!!!

I’d really like to hear from someone with authority on this issue. How much does the average representative allow constituent messages to sway his vote, and how much should he? From a straight polling standpoint, the data seems entirely unreliable. A representative would seem to do much better to simply conduct polling in their district. But then, wasn’t that what elections were for? And shouldn’t they be basing their opinions on what they think is right, period?

This is a problem I have in general with representation. What should a representative make of calls or letters to his office? There just seems to be so much that could be inaccurate about the information. For instance, has some interest group mobilized supporters, in which case the number of calls/letters is a skewed representation.

Or does the issue have a certain appeal to a certain type of voter that might be interested more than others – for instance, a priority for a small number of voters might be 3rd or 4th on the list for the majority, and so a lack of call volume on one side doesn’t represent lack of opinion, but a reflection of how much any one citizen can be involved in every issue.

Then there is just the inherent bias in that there is a certain percent of the population that is more inclined to contact their representative. Does this make their stance any more significant, or indicative of larger sentiment?

And lastly, to what extent does rhetorical competence play a role? Does the fact that I can make a great case for issue X necessarily mean anything more than my fellow citizen who can’t? I mean, what kind of debate is taking place between the message and the congressional staffer? Especially on issues where there is a large volume of messaging, what can really be gleaned from any one constituent? I can’t imagine an aide saying, “Senator, look at this great argument here. They’re really on to something!” I’ve actually had a response from my state Senator, and I couldn’t believe it was really him who penned it. If he didn’t, what point did it serve when we weren’t really going to have a serious discussion. And if he did, doesn’t he have better things to do with his time?!!!

I’d really like to hear from someone with authority on this issue. How much does the average representative allow constituent messages to sway his vote, and how much should he? From a straight polling standpoint, the data seems entirely unreliable. A representative would seem to do much better to simply conduct polling in their district. But then, wasn’t that what elections were for? And shouldn’t they be basing their opinions on what they think is right, period?

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Armchair Teachers

As part of a round table discussion on education reform at The New Republic, Kevin Carey responds to Diane Ravitch:

Kevin, Kevin, Kevin...

Let me just start by assuming that you have worked in a number of poor schools, have an intimate knowledge of the many struggles that face such populations of students and parents - where drugs, crime, prison, delinquency, and behavioral problems are manifest. Let me also assume you've taught at schools where everyone seems generally contented, well rested, fed, secure in their homes and beds. Let me also assume that you have worked with feckless administrations that have no comprehensive vision for a school, and fail to provide vital support where it is needed most - such as disciplinary policy, student intervention, or a basic level of staff leadership building. And you've seen amazing principles that give powerpoint presentations to staff, check in on them frequently, make an effort to hear their concerns and make sure they are well supported, both inside the school and in the community.

I'll also assume that you have worked with classrooms full of students whose parents are unavailable for contact, either because they don't return calls or because their phone has been disconnected. Or in some cases you've maybe found an older sibling who has promised to try and help a student with his or her homework because the parent works late and there is no one else around. You've worked in buildings that are falling apart, where extra duties are arbitrarily assigned, or schedules are changed at the last minute, usually by memo.

I'll assume you've sat with administrators who have never taught in the kind of environment you have (if they have taught at all), have little content knowledge, have no rapport with children and yet are very comfortable filling in the bubbles on a little evaluation form that they base entirely on about 15 minutes total of your teaching. You've smiled as they complimented you on how nicely you've displayed every single standard for your grade in letters too small to read further than 2 feet away yet somehow manage to take up half a classroom wall. I'll also assume you've had a teacher next door who likes to bad-mouth students in racial tones, yet gets along so well with the principle that despite her daily yelling and obvious lack of management skills somehow manages to keep her job.

I'll assume you've struggled with the dilemma of how much to lower your standards in order to keep a student from deciding to give up completely. That you've struggled with what to do with the student who you only see for brief periods of the day, who is grade levels behind, and whose sole mission in life appears to be to do the very minimum to get by, much less make any attempt whatsoever to answer the state tests correctly. I'll assume you've given up your sanity in a daily effort to be the one constant a kid's life, in a world that keeps failing them, for the promise of a decent, salaried union job, with summers off, in which you can reflect on what to do better next year and not worry whether your asshole boss is going to fire you because his boss just didn't like you.

Let me assume that you have seen really good teachers, as well as really bad ones. But for the most part they had their own unique style and that what worked for one didn't always work for another. You saw amazing feats of courage and honesty, dedication and sacrifice, as well as depression, anger, panic, confusion and hopelessness. You saw teachers have good years, then bad. You saw some who were amazing in some areas - such as emotional rapport or enthusiasm, yet weak in others, such as discipline or routine. And vice-versa. You saw different classrooms bring out different dynamics. You saw some teachers barely using any of the curriculum, yet achieving great results. You saw others sticking to the script literally minute by minute, and never seeming to get much out of their kids.

And so what do you think when you hear the rhetoric of the new progressive reformers: accountability, high standards, incentives, charters, evil unions and all the rest? Does any of it seem like it might make much of a difference? Are unions really standing in the way of good teaching? Are charter schools, with the same population and budget going to be any better at sustaining a positive culture of learning and success than public schools? Just because some schools are able to be effective in the current model despite the odds, does that mean that we should continue that model and blame the majority of cases where the model has broken down for any number of reasons?

Is the problem really that all the bad teachers just happen to be at the poorest schools with the most difficult, disadvantaged populations the farthest behind academically, while all the good teachers just happen to be at the nicest schools, with the wealthiest parents and best behaved, most prepared children?

Because I assumed the former, I'll also assume the answers to the latter. To the extent that this wasn't reflected in your piece, I'll pretend that it represented some kind of satire about how out-of-touch wonks who graduated from college and went straight into some think tank, read their copy of education week cover to cover and have a completely idealized and unrealistic impression of what goes on in the classrooms they pretend to write about, much less the actual neighborhoods in which these classrooms exist, and who sit in their cozy DC offices and pen odes to some newfangled Utopian scheme that simply won't work on a national or state-wide basis. Because surely, the cognitive dissonance would be just too much to bear. It would be like Orwell climbing out of the coal muck and then writing about how those lazy miners just need to pep up a bit and work a bit smarter in order to avoid those pesky injuries.

I'll end with a prescription you seem to think is required of Ms. Ravitch before she goes poking holes in your grand new theories.

The achievement gap in America is entirely structural. Our current system basically acts as though there is no such thing as socio-economic status, and that it has little bearing on education outcomes. The new reformers never tire of presenting examples of schools which do with public money what other schools can't. That's fine as far as it goes, which isn't very far. These schools often get outside money, require excessive and unsustainable, non-market-scalable sacrifices from their teachers, or simply enjoy the tidy convenience of having their stars align.

The long of the matter is that we are expecting to get similar outcomes with very different populations. If you know the first thing about early childhood and SES in education, you know that poor kids are disadvantaged in many ways, and that shows up in their ability to perform at school. The website schoolperformancemaps.com shows rather neatly just how wedded SES is to API, giving a detailed look at the geography of achievement.

Title I funding is a drop in the bucket. While some of it is good, and targeted, it needs to be ramped up tremendously, and expanded beyond the school walls. These are community problems after all that we are talking about. Susan Neuman has done good work on determining what kinds of targeted community programs have produced results in early childhood. The Harlem Children's Zone has incorporated much of this philosophy into its plans. Literally, direct intervention needs to be happening in hospitals - actually sooner. Poor mothers need to be enrolled in parenting programs. Environmental monitoring needs to be done to check for lead and other toxins. Community initiatives need to be created that expand on the public library model, into technology and learning clinics, where parents can learn everything from English to nutrition, to discipline and cognitive behavioral training. Home nurse visits need to be made an integral part of every poor child's life. Academic progress can be monitored, as well as emotional and health check-ups.

Because as it stands right now, the kid shows up in Kindergarten out of the blue. He gets a free lunch, and is shunted into a class with 30 other kids. The teacher is then expected to get every body at or above grade level in a positive, rewarding and healthy manner so that school is a place they actually enjoy. But then they're out the door and on their own until tomorrow. Neither the school nor the teacher has the adequate resources to guarantee that every single kid that comes through that door - and then leaves 13 years later - can be adequately said to not have been "left behind".